Full Report

Annual Learning Report 2021/2022

Full Report

Annual Learning Report 2021/2022

About This Report

This report is Lambeth Early Action Partnership’s (LEAP) first programme-level evaluation output. It summarises initial evidence of LEAP’s progress towards our intended impact of improving Early Child Development outcomes for children in our target areas.

The first in a series of annual reports on LEAP’s progress, it allows us to test the efficacy of LEAP’s Theory of Change, identify areas for reflection, further research, and potential programme improvements.

As the programme moves into its final years, annual reports like this one will be complemented by the other outputs of LEAP’s local evaluation. This will include both formative and summative evaluations delivered by an external research partner.

For more information about LEAP or this report, please contact leapevaluation@ncb.org.uk.

Message from Laura McFarlane, Director

I am delighted to introduce our first Annual Learning Report.

The findings contained in this report give us a real opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of our programme. The report shows how our services are supporting children and families to have a better start, whilst also giving us crucial insight into which families we are engaging and working with via our services.

There is much to celebrate in this report!

To date, LEAP services have worked with over 14,200 children and families. Many families rate LEAP services very highly and parents report feeling more knowledgeable and confident in supporting their child’s development.

We are on track to achieve our early goal of giving more than 10,000 children aged 0-3 in Lambeth a better start in life.

This report also offers food for thought. We are committed to continue learning from these emerging findings to further our understanding of the families in the LEAP area and how our services are received.

Many people are involved in bringing these insights together. From parents who complete questionnaires and feedback forms, to practitioners who regularly submit data. The LEAP Core Team have skilfully analysed and presented these findings, so we are able to share our learning. I would like to offer my thanks to all involved in this work.

I invite you to read the summary report for an overview of the findings and then dive deeper into this full report for detailed analysis of some of the outcome areas LEAP works on.

As we approach the final stages of the LEAP programme, I am confident that the insights and stories contained in this report will enable us to focus on areas for improvement and development as well as creating a strong evidence base for our local Lambeth system and beyond.

I hope you will find this report useful and inspirational.

Laura McFarlane

Director

1.0 Executive Summary

1.1 About LEAP

Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP) is one of five local partnerships which make up A Better Start, a national ten-year (2015 – 2025) programme funded by The National Lottery Community Fund that aims to improve the life chances of babies, very young children, and families.

LEAP works with a wide range of children, families, practitioners, and organisations across Lambeth. We fund, improve, and evaluate over 20 local services, meeting the needs of families through pregnancy and the early stages of childhood.

Our aim is to:

- Improve early child development outcomes for all children living in the LEAP area

- Reduce local inequalities by supporting those at a greater risk of poor outcomes

LEAP delivers services in parts of Lambeth (the LEAP area) where young children experience greater inequalities than children in the rest of the borough.1 The LEAP area is home to almost a fifth of children under 4 in Lambeth.2 While LEAP has some targeted services that are only available to families living in the LEAP area, other services are available to all families living in Lambeth, and some are open to anyone who wants to attend.

Services fall into two groups:

- Services that work directly with children to help them reach their development milestones.

- Services that support children indirectly, by working with parents, early years practitioners, and the wider community, so they are better equipped to provide the responsive relationships and positive experiences that children need.

LEAP is a collective impact initiative, which means that all our services and activities link together and work towards shared goals to improve outcomes for young children.

1.2 About this research

This report presents emerging insights about our overall reach and the learning taken from our internal Shared Measurement System. It has been written by LEAP’s team of researchers and analysts.

We routinely collect and analyse data from across the programme. This helps us monitor performance across services, track progress towards outcomes, and continuously learn and improve. Data is stored in our innovative Integrated Data Platform. We have been collecting some data since the start of LEAP in 2015, including the number and demographics of people accessing our services. However, some feedback and outcomes data has only recently been collected as part of our Shared Measurement System (which started in 2021).

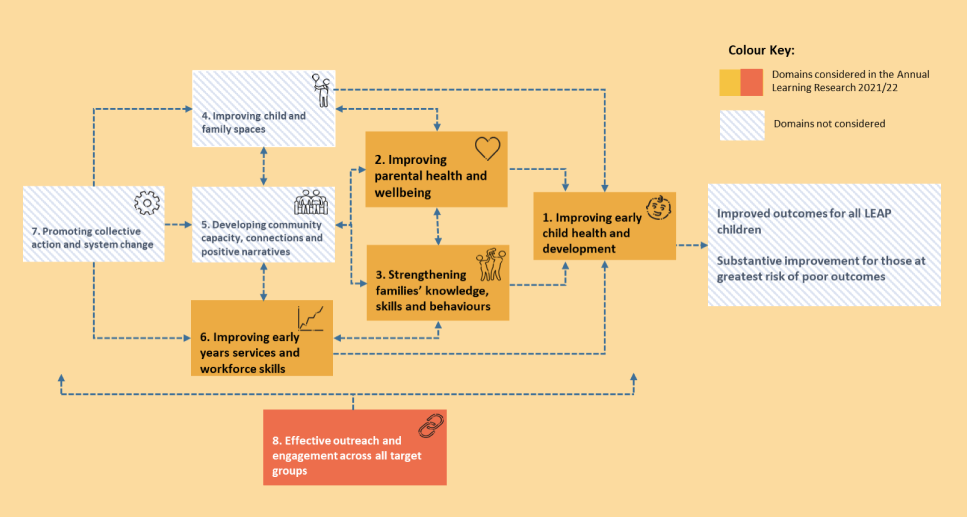

This report presents findings on the engagement with LEAP services across the complete programme portfolio. This report then shares findings from across the programme on four of our Theory of Change outcome domains: 1, 2, 3 and 6. These domains had the best data available at the time our analysis began in March 2022.

By analysing routine service data, LEAP intends to learn what works in early years, to improve both evidence and practice. These findings will be used internally by the LEAP team to drive learning and improvement. By sharing them publicly, we also seek to build external knowledge of the LEAP programme.

1.3 Reach & Engagement

Key findings

- Over the lifetime of the programme, LEAP services have reached over 14,200 children and families (6,966 children and 7,239 parents or carers).

- An additional 5,038 individuals have been reached through our lighter touch community engagement activities which include festivals and events curated by the LEAP community engagement team.

- Families engaging with LEAP services broadly reflect the ethnic diversity of the population, though anecdotally we know there are still some groups who are less likely to engage.

- 49% of families engaged in services live in the LEAP area. Another 42% live in other areas in Lambeth, while 9% live outside the borough.

- Mothers account for 87% of the parents and carers we engage, while fathers account for only 7%. The remaining 7% are made up of other carers such as other family members and childminders.

- The vast majority (85%) of children and families who engage with LEAP attend only one service, with 14% attending between two and four services.

- LEAP has provided capacity building support to 1,681 practitioners across the early years workforce.

Reflections on our engagement

It is encouraging to see that the LEAP programme is on track to achieving our goal of giving more than 10,000 children in Lambeth a better start in life. It is also encouraging that the ethnic background of families engaged with LEAP services broadly represent the demographics of the wider population, demonstrating the programme’s capacity to engage with families and to appeal to the full diversity of the area’s communities.

Fathers’ participation in LEAP services is limited. Whilst this is not unexpected given wider societal barriers to fathers’ involvement in the early years, we will continue to think about LEAP-specific barriers that might impede fathers from accessing services.3 4

We are also interested in speaking with families and practitioners to understand more about the reasons influencing some families to attend multiple services as this would give useful insight into pathways for parents and carers. We would also like to hear from families from the LEAP area who haven’t participated in any services at all.

1.4 Child Health & Development

To achieve improvements in child health and development, LEAP offers several universal and targeted services working directly with early years children and families. Services measure child outcomes using a series of different measurement tools to assess impact.

Specifically LEAP works with:

- Pregnant women to provide enhanced maternity care as well as specialist nutrition and wellbeing support to improve birth outcomes

- Babies and their caregivers to promote secure attachment

- Young children in Children’s Centres and childcare settings to improve communication and language development

Here, we present emerging findings from two of these services where the data is most complete.

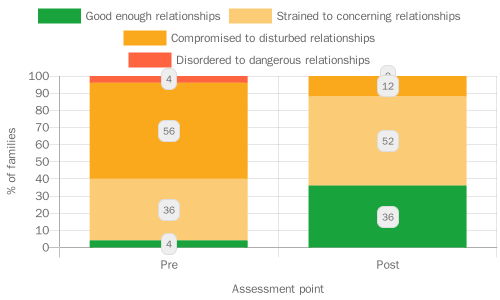

LEAP’s Parent and Infant Relationship Service (PAIRS) one-to-one support, delivered by a specialist Parent-Infant team, aims to improve the relationship between a parent or caregiver and their baby or young child. Clinicians work directly with parents or carers and their infant, or with expectant parents before birth, to promote secure attachment and positive, sensitive, and responsive parenting. Data from 28 families shows an improvement in family relationships and a reduction in observable difficulties for infants after engagement with the service, as seen in Figure 2 below.

Further information about LEAP’s PAIRS One-to-One Service and the outcome measures we use to monitor change, can be found later in this report.

LEAP’s Natural Thinkers Service

Children living in the LEAP area are less likely to have a private garden and good access to green space.5 Given this, LEAP delivers the Natural Thinkers programme which supports early years practitioners to provide high quality outdoor learning for children and more recently offers local ‘stay and play’ sessions for families. The aim of this service is to improve children’s wellbeing and their communication and language development.

It’s a highlight of our week as we live in a flat with no outside space & she has become confident exploring this session as if it were her own garden.

Looking for frogs and newts and actually finding them. Children absolutely loved hunting. Also, the hunt and find various insects and leaves with a tick-off sheet was so much fun too.

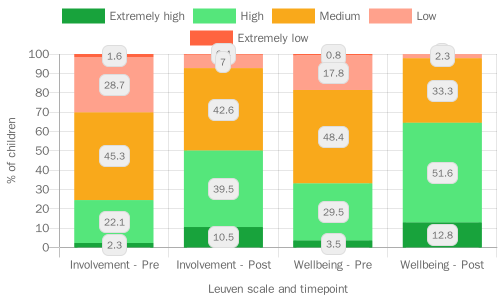

Data collected from 147 children, show children were more involved in activities and had improved wellbeing at the end of the service.

Boys had lower levels of involvement and wellbeing compared with girls at the initial assessment, but this gender gap had narrowed by the end of the programme, which suggests that Natural Thinkers activities may be particularly beneficial for boys.

1.5 Parental Health & Wellbeing

Having good physical and mental wellbeing is important in enabling parents to provide a positive, healthy, and stable home environment for children. By contrast, being in poor health or experiencing mental health issues can be a barrier to positive parenting6.

LEAP works with parents at the following stages:

- In pregnancy and postnatally

- In the early years through group sessions

LEAP also provides support to parents at risk of, and experiencing, domestic abuse during pregnancy or their child’s early years.

Here we present emerging findings from two of our services that work directly with parents and caregivers to improve their health and wellbeing.

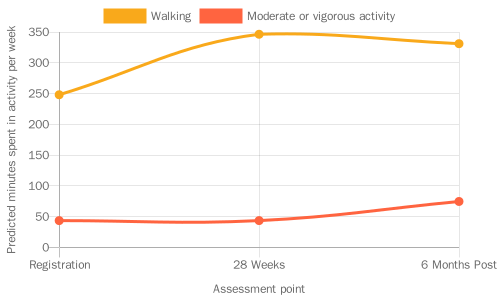

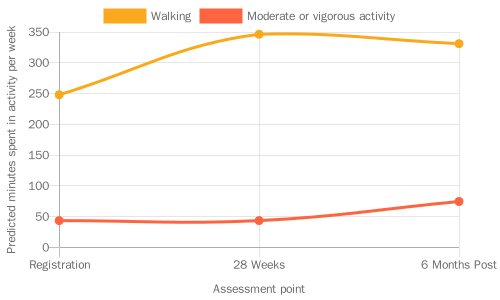

LEAP’s Community Activity and Nutrition (CAN) service is a targeted programme that aims to support pregnant women in the LEAP area with a BMI of over 25 to adopt healthier diet and activity behaviours. It has a specific focus on engaging women from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds. 77% of women engaged by the CAN service are from these backgrounds.

Data from 485 women shows that CAN is helping all women to be more physically active by walking more during pregnancy. This increase in physical activity is continued postnatally (Figure 4). Women from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds have lower levels of physical activity when entering the service, a difference which is consistent with national surveys. This difference is seen both before and after participation in CAN.7

In future research, we hope to explore birthweight outcomes for CAN participants, linking these to physical activity data and participant characteristics. Find out more.

LEAP’s Enhanced Casework (Gaia) service offers holistic support to LEAP parents who are experiencing, or are at risk of, domestic abuse during pregnancy or their child’s early years. This includes emotional support and practical assistance with issues such as housing and legal matters.

By the end of engagement with the service, just over a third (36%) of clients said that they had experienced an end to all types of abuse and controlling behaviours. Abuse frequently continues for years after the end of a relationship, so this finding is not unexpected. It highlights the importance of signposting people to continued support. After engaging with the service, all clients said they now felt confident about accessing help and support relating to domestic abuse.

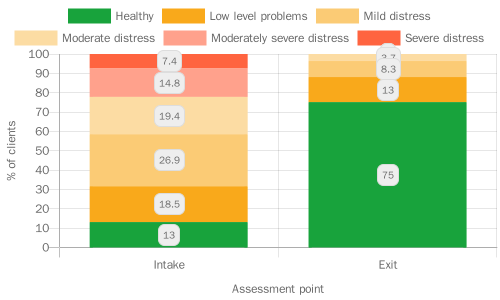

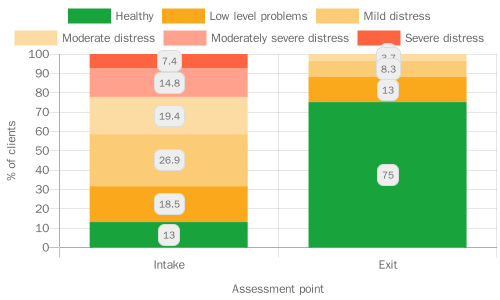

The Enhanced Casework team monitors changes in clients’ levels of psychological distress using the CORE-10 validated measure. Analysis of average scores shows a significant decrease in clients’ psychological distress from intake to the last session. At exit, no client had severe or moderately severe distress, compared with 22% of clients at intake (See Figure 5 below).

1.6 Parental knowledge, skills and behaviours

LEAP services aim to equip parents with the knowledge, skills, and behaviours they need to provide their very young children with the best start in life. Here we report on findings from services which focus on behaviours that we know have a positive impact on children’s long-term outcomes. These include positive parenting, the home learning environment, and breastfeeding.

Parenting and parent-infant relationship

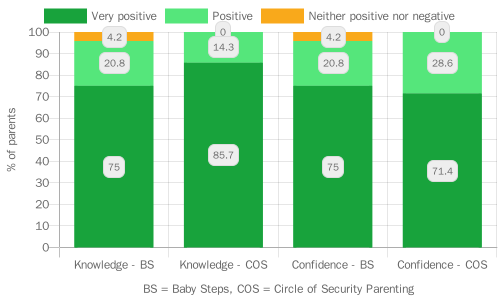

- As a result of participating in the Baby Steps programme and/or the Circle of Security Parenting programme, parents feel more knowledgeable and confident about parenting, and enjoy being a parent more. Some parents, however, still felt low or moderate confidence about dealing with the stresses of being a parent. LEAP would be interested to explore this with families to understand if there is more we can do to support their confidence about managing these stresses.

- Parents taking part in LEAP’s Baby Steps programme developed a closer relationship with their unborn baby over the course of the programme (measured using the Prenatal Attachment Inventory).8 Though attachment does tend to increase throughout pregnancy9, it is encouraging that we observe a significant positive change among Baby Steps participants, as higher levels of prenatal attachment are associated with positive health behaviours in mothers and secure attachment in infants.10 11

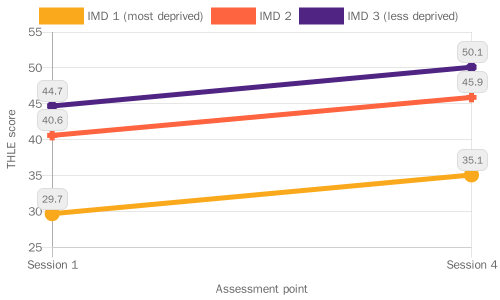

- Pregnant women living in relatively less deprived areas, however, seem to have better attachment to their unborn babies than pregnant women living in more deprived areas. This difference is seen both before and after participation in Baby Steps. Risk factors for the development of prenatal attachment include poor maternal mental health, minimal social support and smoking during pregnancy. These factors can be more prevalent (seen more often) in mothers from less advantaged backgrounds.12 LEAP continues to try to better understand and address differences in prenatal attachment.

- A caregiver’s perception about their infant’s thoughts, feelings and intentions towards them plays a large part in how the caregiver behaves and interacts with their infant. This has consequences for the infant/child. Feelings of ‘warmth’ (e.g., ‘my baby smiles at me’) positively influence the development of the caregiver-infant relationship, while feelings of ‘invasion’ (e.g., ‘my baby wants too much attention’) can have a negative impact. Participation in Circle of Security Parenting seems to strengthen the relationship between parent and baby, significantly increasing feelings of warmth and decreasing feelings of invasion (measured using the Mothers Object Relations Scale).13

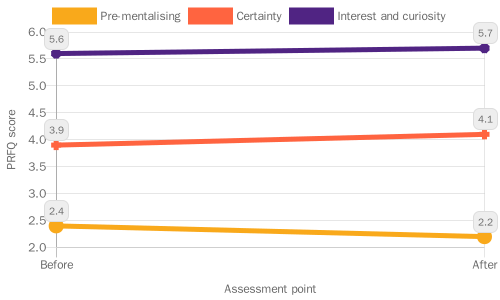

- Reflective functioning refers to a parent’s ability to think about their own and their child’s mental states (e.g. feelings, desires, wishes, goals and attitudes). This ability is an important steppingstone to other positive parenting behaviours, such as responsiveness, which helps the development of secure attachment and emotional regulation in children.14 Parents who engage in LEAP’s Parent and Infant Relationship One-to-One Service experience some improvements in reflective functioning (measured by the Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (PRFQ).15

Home learning environments

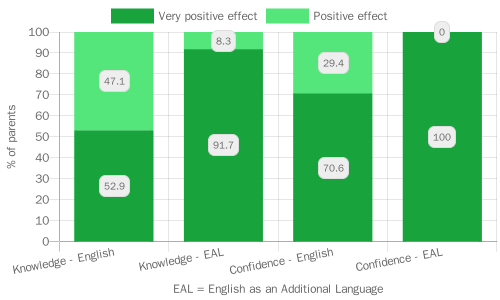

- Two of LEAP’s communication and language development services, Sharing REAL and Supporting Babies’ Next Steps, are helping all parents to feel more knowledgeable and confident in supporting their children with early communication and language. This impact was most notable for parents with English as an additional language who overwhelmingly reported a very positive change in their knowledge and confidence. Approximately 40% of parents and carers that take part in LEAP’s communication and language development services speak English as an additional language. As children with English as an additional language are significantly less likely than their peers to have a good level of development at the end of reception year16, this may be an area in which LEAP is helping to reduce inequalities. LEAP will be working with our CLD services to better understand how and why LEAP’s CLD services may be particularly beneficial to parents with English as an additional language. Our aim will be to share this learning across the programme and beyond.

1.7 Practitioner skills and early years services

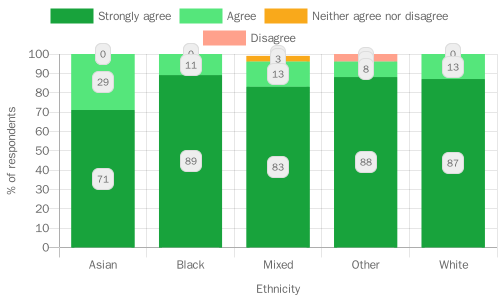

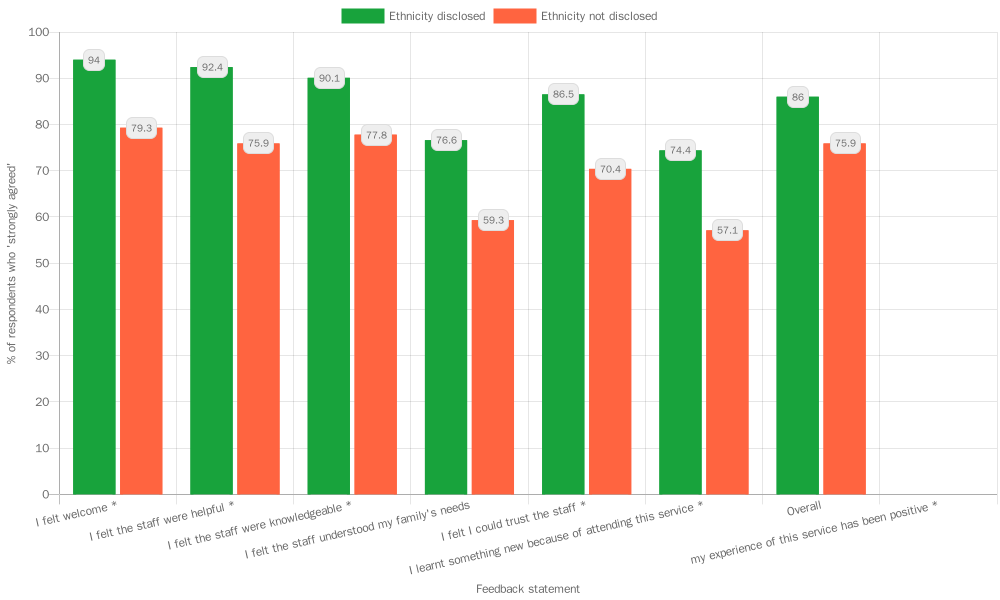

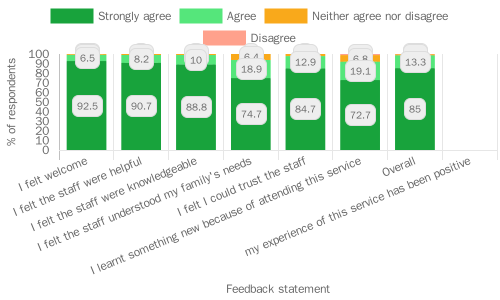

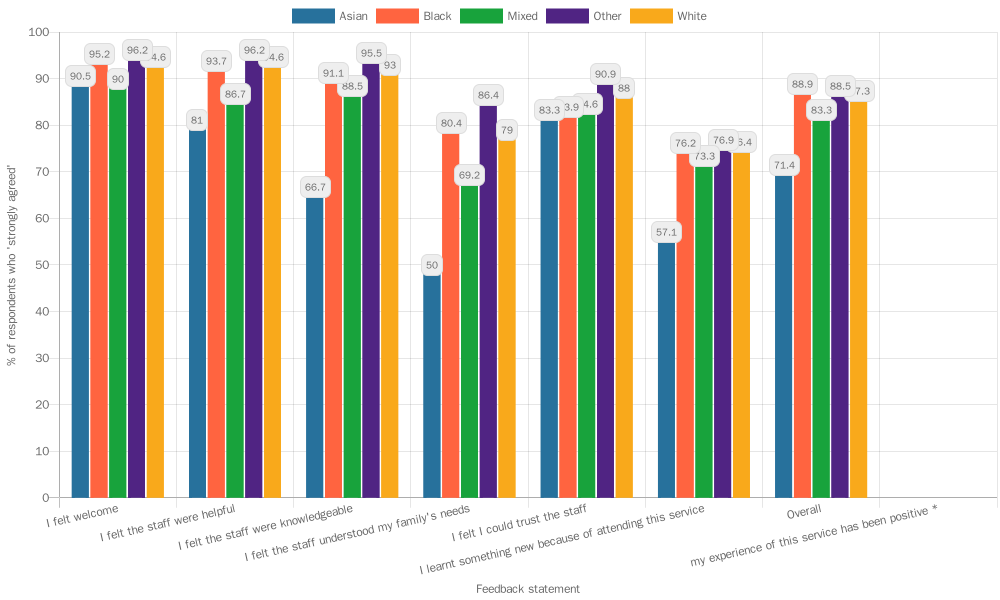

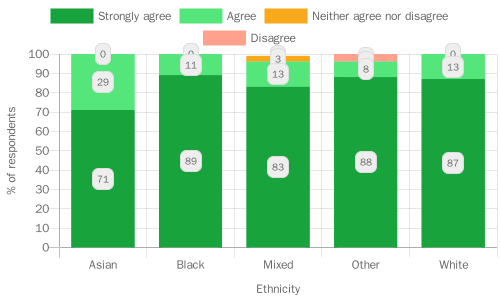

Feedback on LEAP overall is very positive, with families rating their experience of LEAP services very highly. Families say they find staff and volunteers to be welcoming, helpful and knowledgeable. Families trust LEAP staff and volunteers and feel that they understand their needs.

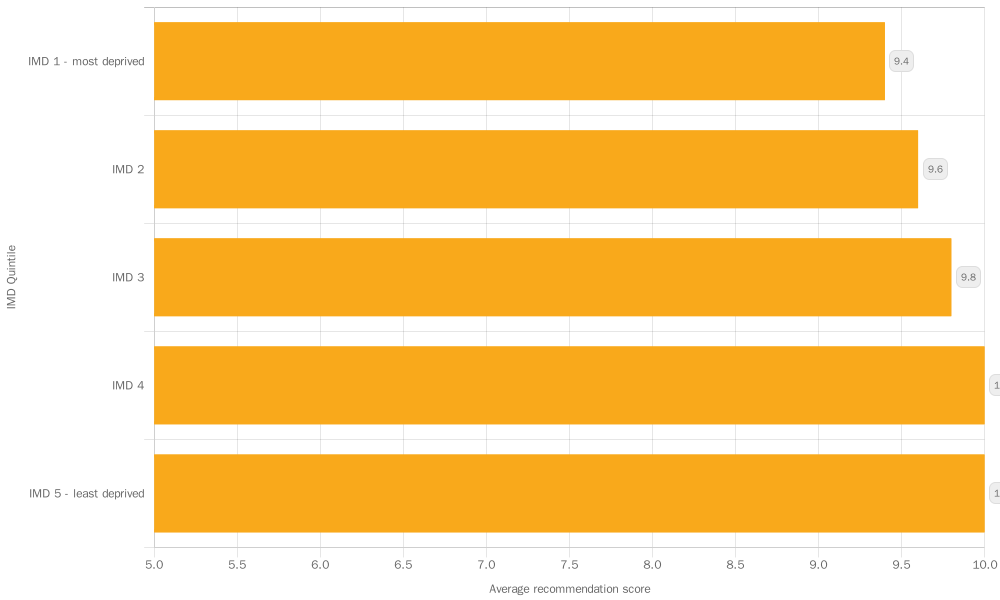

LEAP’s approach is underpinned by our work with communities and peer engagement. We’ve found that families are extremely likely to recommend LEAP services to their friends and family (based on LEAP’s overall recommendation score). This is true for all families, across all ethnic groups and for families living in relatively more and less deprived areas. Asian families, however, when compared with families from other ethnic backgrounds, were slightly less likely to strongly agree that overall, their experience of LEAP services had been positive. We don’t know why this is, but this is an area that might warrant further investigation.

We also found that families living in more socio-economically deprived areas of Lambeth and surrounding neighbourhoods were less likely to ‘strongly agree’ that they trust LEAP staff and learnt something new from LEAP services, compared with families living in relatively less deprived areas. This mirrors other studies that have found a link between families experiencing financial difficulties and levels of trust and engagement with support services, because of factors including daily stress and previous negative experiences of public institutions.17 18

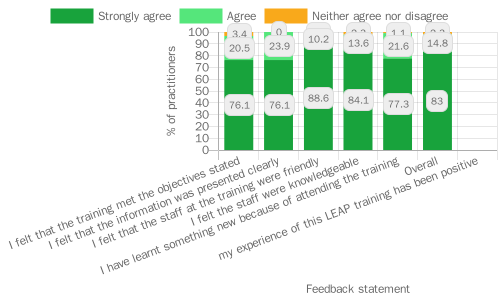

LEAP also provides training and professional development opportunities to local practitioners to help support the provision of high-quality early years services. Practitioners rate LEAP’s support very highly, providing consistently positive feedback. Practitioners are highly likely to recommend LEAP’s workforce offers to their colleagues.

The facilitator was very warm, approachable, clear, patient with our questions and very helpful.

1.8 Conclusions

The findings presented in this report demonstrate the achievements and progress of LEAP services to date, both individually and collectively. In terms of overall reach and engagement, LEAP is steadily working towards achieving our initial target of engaging 10,000 children. LEAP is also demonstrating success in being able to engage families from diverse backgrounds, reflecting the overall LEAP population. This finding is extremely important in demonstrating our contribution to reducing inequalities at the population level. There are, however, some areas to explore about further improving our reach and engagement, particularly in terms of paternal involvement and pathways supporting parents and families to use multiple services.

Within the specific domains explored in this report, the changes in outcomes measured by validated tools are promising indications of the positive impact of the specific services. The PAIRS One-to-One Service is innovative in its approach. These initial indications of improved attachment could be very significant for services within Lambeth and beyond. Likewise, improved outcomes in pregnancy demonstrated by an increase in physical activity and improved parenting knowledge and practice also hold great promise. Better understanding of patterns of inequality in outcomes will be crucial moving forwards.

In this report it has not been possible to share outcomes across all services due to data availability, but LEAP continues to build our database of quality evidence through our Shared Measurement System. Future annual learning research will include larger and more complete data sets, covering all key domains of our theory of change, as well as additional child development outcomes data. Additionally, we intend to gain access to some key administrative data sets and to have linked data from Health Visiting and the National Child Measurement Programme data sets.

LEAP is also committed to continued learning and will invest in additional research activities outside of the routine monitoring data which is presented here. Specifically, LEAP will invest in detailed reviews of the services as well as a programme-wide evaluation to be conducted by our partner Dartington Service Design Lab. In addition, we will work closely with our partners in Lambeth and beyond to share and build on the early findings presented in this research. We will spread good practice and work together to address challenges and difficulties affecting our local populations, particularly in light of the current Cost of Living crisis.

2.0 Introduction to LEAP

Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP) is one of five local partnerships which make up A Better Start (ABS).19 ABS is a national ten-year (2015-2025) programme funded by The National Lottery Community Fund which aims to improve the life chances of babies, very young, and families by changing the way services are commissioned and delivered.

LEAP is made up of parents, early years practitioners, Children’s Centres, the National Children’s Bureau, Lambeth Council, NHS trusts, community organisations and several local charities.

LEAP uses a place-based, collective impact approach to achieve our ultimate goals. This means that LEAP brings together people and organisations to share information and work in mutually reinforcing ways to contribute to the intended impact of:

- Improved Early Childhood Development outcomes for all LEAP children.

- Substantive improvement for those at greatest risk of poor outcomes.

2.1 LEAP’s approach

Evidence shows that early intervention can improve outcomes for children and families20, but there are limits to what single initiatives working in isolation can achieve21. This is because children’s lives are shaped by multi-level and interactive influences, including family, education and care, neighbourhood, and social and cultural contexts22 23 24.

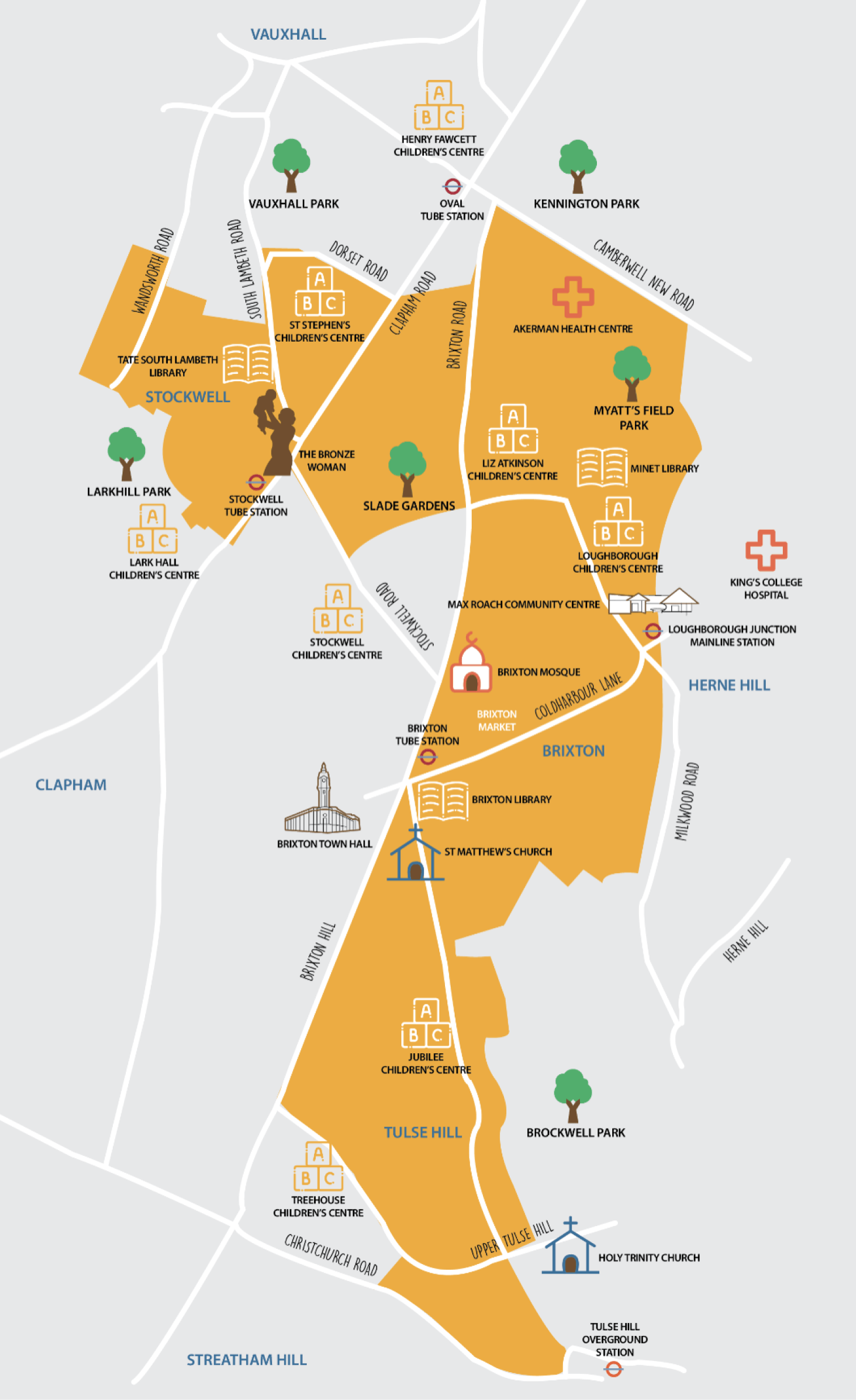

As a place-based programme, LEAP aims to support children and families living in a select area of Lambeth (See Figure 7) by:

- Focusing on factors that influence child health and development and local causes of inequality;

- Creating a network of joined up, accessible services;

- Working in partnership with the local community; and

- Collecting data to learn what works.

A note on the LEAP area

Throughout this report we make reference to a number of geographic areas:

- LEAP – Most of the data included in this report was collected prior to ward boundary changes in 2022, therefore the LEAP area refers to four wards used prior to this change: – Coldharbour, Stockwell, Vassall, Tulse Hill

- Non-LEAP Lambeth – all Lambeth wards excluding the four LEAP wards noted above

- Non-LEAP other borough – boroughs other than Lambeth

2.2 LEAP’s Services

To achieve its intended impact, LEAP funds, continuously improves, and evaluates over 20 services in the LEAP area. These fall into two groups:

- Services that work directly with children to help them reach their developmental milestones;

- Services that support children indirectly, by working with parents, early years practitioners, other professionals, and the wider community.

LEAP services support families at every step through pregnancy and the early stages of a child’s life. As a collective impact initiative all of LEAP’s services and activities link together and work towards shared goals around improving children’s outcomes. LEAP works across three interrelated strands encompassing children’s:

- Diet and nutrition;

- Social and emotional development;

- Communication and language development.

More detail on LEAP’s current services can be found in Appendix 3.25

3.0 Aims & Objectives

This is the first in a series of annual evaluation reports which will look at LEAP’s progress towards our intended impact.

The foundations of LEAP’s evaluation are our programme and service-level Theories of Change (ToC) and a Shared Measurement System (SMS) which has been implemented over the last year. These reports will seek to test out LEAP’s Theory of Change, to see if the programme is working as intended. As LEAP moves into our final few years, these reports will complement and summarise the other outputs of LEAP’s local evaluation.

This first report explores LEAP’s new Shared Measurement System data, looking across our services at a programme-level to explore emerging insights about our impact.

At a programme-level, it has the following objectives:

- Assess the extent to which LEAP is reaching and engaging our target population.

- Summarise progress towards LEAP’s medium-term and long-term outcomes.

- Identify areas in which our Theory of Change is not working as intended and potential explanations for this.

3.1 How you can use this report

At LEAP, we want to share these emerging findings to stimulate discussion about what the data is telling us so far, about our approach to measuring collective impact, and about what we might want to do or change as a result of these findings. We hope this report will generate conversations that will inform our future evaluation outputs. To this end we invite you to share your thoughts, feedback and ideas with the LEAP Evaluation and Research team: leapevaluation@ncb.org.uk.

Beyond its immediate objectives, this report has a number of secondary aims:

- For the LEAP team and our partners:

- To build our knowledge of the LEAP programme and inform our understanding of the efficacy of LEAP’s programme-level Theory of Change.

- To demonstrate the scope of our data and the possibilities for analysis and learning.

- To celebrate the progress we have made towards achieving our outcomes and to identify areas for reflection, further research and potential programme improvements.

- For other interested organisations or individuals:

- To give an overview of LEAP’s work and our approach to evaluating a place based collective impact initiative including the limitations and opportunities presented by our Shared Measurement System.

- To present emerging evidence of changes resulting from our work: services making an impact on outcomes, and how the programme is working together as a collective.

- To connect with LEAPs evaluation work. This report is the first programme-level evaluation output, and we hope it provides a starting point for discussion and shared learning.

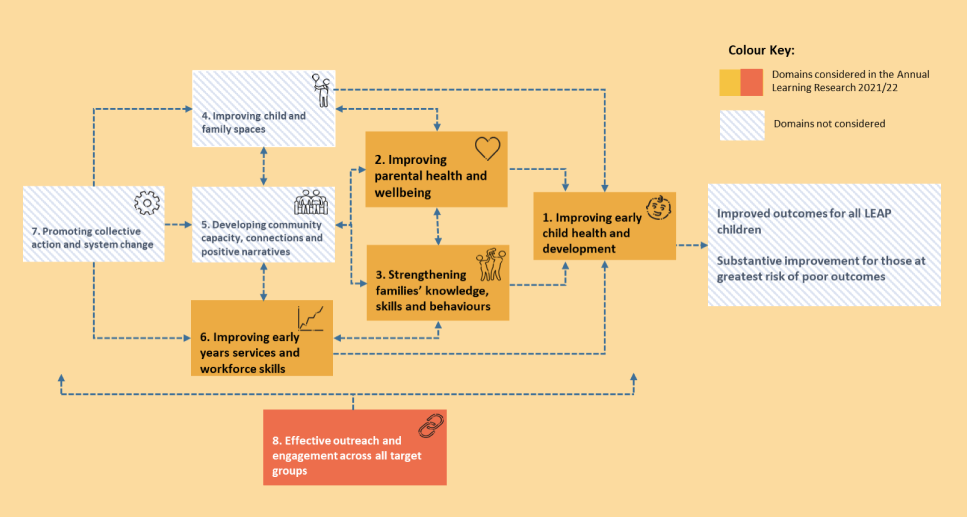

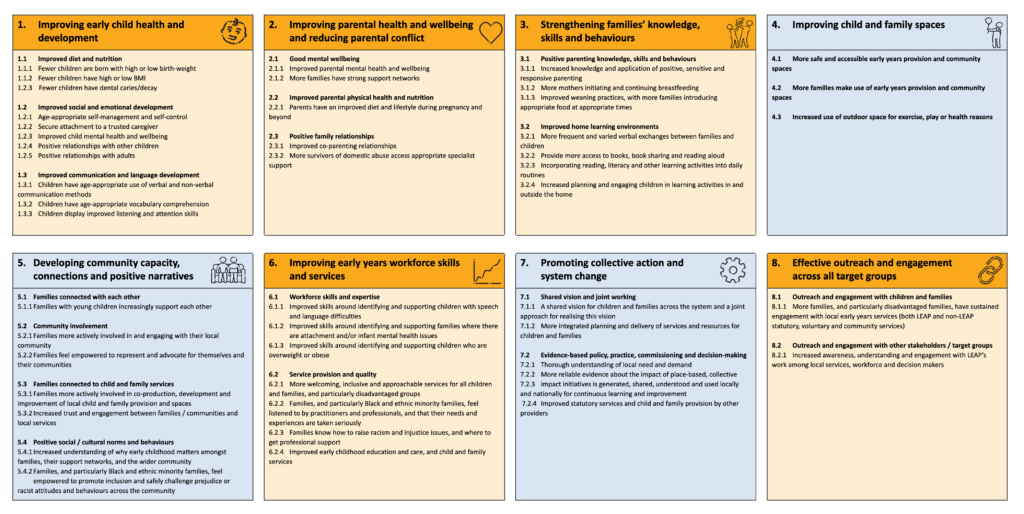

3.2 Background to this LEAP Annual Learning Report

This report focuses on five of the eight domains or outcome areas from LEAP’s programme Theory of Change (See figure 8 for our Theory of Change with these domains highlighted). These are the five areas which at the time of writing this report, are best evidenced by the data we have collected so far.

What limitations are there to our data?

Throughout this report we try to make it clear where gaps in the data prevent us from answering certain questions or undermine the certainty of our conclusions. We also highlight areas we’ll be able to speak about with more certainty in future learning reports.

A key limitation is that our Shared Measurement System does not currently collect data on all eight LEAP domains. Some domains, such as ‘Promoting collective action and system change’, will require a distinct approach to measurement which will be developed with our local evaluation partner (Dartington).26

In addition, many findings presented in this report are preliminary results that will require further validation. While reach and engagement data has been collected over the lifetime of the project, several outcomes measures are new to services and families, and some services have not yet collected enough data for analysis. We have still listed services against outcomes included in this report, even if they haven’t been included in analysis yet, to show how LEAP is working across our intended outcomes.

Our ambition is that next year’s Annual Learning Report (2022/23) will address some of these gaps, by which point the Shared Measurement System will have been in operation for over a year and a much fuller data set will be available to enable a more rigorous exploration of the evidence.

3.3 What’s in the report?

Chapter 2 provides an introduction to LEAP and Chapter 4 gives an overview of how we are measuring our impact.

Chapter 5 (Domain 8 – Effective Outreach and Engagement Across All Target Groups) analyses the user and engagement data from across the programme to understand who is engaging with LEAP’s services and offers a breakdown of LEAP’s families by details such as ethnicity, age, and home language.

Chapter 6 (Domain 1- Improving Early Child Health and Development) provides a look at the long-term outcomes data LEAP has begun to collect on indicators of early child health and development including: obstetric outcomes, children’s diet and nutrition, children’s social and emotional development, and communication and language development.

Chapter 7 (Domain 2 – Improving Parental Health and Wellbeing and Positive Family Relationships) looks at medium- and long-term outcomes data around parental physical and mental wellbeing. It looks at LEAP families’ diet and physical activity levels, during pregnancy and after, parental mental wellbeing, and family relationships.

Chapter 8 (Domain 3- Strengthening Families’ Knowledge, Skills and Behaviours) considers medium- and long-term outcomes data to explore whether LEAP parents are developing the knowledge, skills and behaviours that children need to have the best start in life. This section includes data on positive, sensitive, and responsive parenting, and creating a positive home learning environment.

The final section of analysis in Chapter 9 (Domain 6 – Improving Early Years workforce Skills and Services) provides analysis of the feedback data collected from families participating in LEAP’s services, as well as practitioners participating in LEAP’s training and workforce development activities. This section looks at what people thought about the quality of LEAP’s services and their suggestions of what could be improved.

Chapter 10 reflects on some conclusions, implications and recommendations resulting from this work.

For an overview of the quantitative and qualitative research methods used for this report, see Appendix 4.

4.0 Measuring LEAP’s Impact

In the first five years of LEAP (2015-2020) we focused on establishing and developing services. In the second half (2021-2025) we are focusing on monitoring progress and evaluating the effectiveness and impact of LEAP as a programme.

LEAP has a three-layered approach to evaluation27 which consists of:

- The National Evaluation of A Better Start, overseen by a consortium of partners led by NatCen Social Research (NatCen).

- The Local Evaluation of LEAP, delivered by Dartington Service Design Lab, LEAP’s Local Evaluation partner.

- LEAP’s in-house Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning, led by our Evaluation and Research team. This learning report sits in this layer.28

Between 2019 – 2021, we worked with services, partners and families to refresh our service, domain and programme Theories of Change.29 These are our blueprint for LEAP’s evaluation. We also developed a Shared Measurement System.30

4.1 Theories of Change

The scope and ambition of LEAP means there are numerous possibilities for data that could be collected. To narrow the focus, and to ensure LEAP measures what matters the most, LEAP has adopted a Theory of Change (ToC) approach.

What is a Theory of Change?

An effective Theory of Change describes the activities an intervention intends to deliver and the changes, or outcomes, it expects to see in the short, medium, and long term as a result. It is a useful tool because it enables services to develop a set of key learning questions: the information they need to make sure delivery and impact are as good as they can be.

To capture the impact of LEAP’s individual services, and their collective impact as a programme, LEAP has developed Theories of Change at both the service and programme level. The overarching programme-level Theory of Change is divided into eight different but interconnected domains, these are:

- Improving early childhood health and development

- Strengthening Families skills knowledge and behaviour

- Improving parental wellbeing

- Improving child and family spaces

- Developing community capacity, connections, and positive narratives

- Improving early years services and workforce skills

- Promoting collective action and systems change

- Effective outreach and engagement across target groups

Each service’s Theory of Change corresponds to at least one of these domains. For example, Natural Thinkers works to improve early childhood health and development (domain 1) and to improve early years services and workforce skills (domain 6). For a closer look at LEAP’s domains and related work, see LEAP’s Interactive Theory of Change.31

4.2 LEAP’s Shared Measurement System

LEAP’s SMS enables us to explore how LEAP services are working together to achieve the programme outcomes. The SMS integrates data from across LEAP’s services and activities, and enables the LEAP team to monitor performance, compare performance across services, track progress towards outcomes, and identify opportunities for learning and improvement.

LEAP’s SMS includes:

- A common set of outcome measurement tools;

- Output indicators to support practitioners to monitor their delivery;

- Key Learning Questions across all services;

- Simplified data collection procedures to reduce the burden on practitioners;

- Additional data support for services to support accurate and robust collection of data; and

- An integrated data platform to support data reporting and analysis.

The key feature of LEAP’s SMS is a common set of outcome measurement tools. To inform the selection of tools, we commissioned an evidence review of effective measures, delivered by The Right To Know in 2021. The measurement tools were agreed using the evidence review and following discussions with subject-matter experts, families, service leads and key LEAP partners. The tools were selected to generate high-quality, robust evidence to be used in our evaluation.

To learn more about the development of LEAP’s SMS, and for the full set of measurement tools, see LEAP’s Practitioner Guide.30

4.3 LEAP’s Data Types

For each service, LEAP routinely collects six main types of data:

- Input data – the financial, human, and material resources used in planning and delivery.

- User data – the characteristics and demographics of the people accessing services.

- Engagement data – how many people engage with services and how often.

- Feedback data – what families and practitioners think of services.

- Medium-term outcomes data – the medium-term changes LEAP wants to achieve.

- Long-term outcomes data – the longer-term changes LEAP wants to achieve.

Input, user, engagement, and feedback data will enable us to understand whether services are:

- being delivered as planned;

- reaching their intended target population32; and

- of a good quality and are being rated well by families and practitioners.

Outcomes data will help determine:

- if and how LEAP has contributed to positive change for children, families, Early Years practitioners, professionals, and the wider community; and

- to what extent LEAP has contributed to reducing inequalities.

4.4 LEAP’s Data Integration Platform

The data collected through the SMS is stored on LEAP’s Data Integration Platform. The platform was developed to bring together pseudonymised data from across LEAP’s different services and enable a programme-level view.

The platform captures individuals’ journeys through LEAP’s services allowing LEAP to see the combination and sequencing of services accessed by families, and the effect of this engagement on outcomes. Hence, the platform is essential to evaluating the collective impact of the LEAP programme. To read more about the Data Integration Platform see Appendix 4.

4.5 LEAP’s in-house Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning

This Annual Learning Report forms part of LEAP’s in-house Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning. It builds on and complements the Quarterly Service Reports (QSRs)33 which have been developed over the past year.

The QSRs aim to support services to:

- answer questions related to their Theory of Change

- see how their service is performing and make improvements if needed; and

- better understand the families using their service.

5.0 Effective Outreach & Engagement Across Target Groups

Key Findings

- LEAP has reached a total of 14,205 individuals over our lifetime, including a diverse range of people of different ages, ethnic backgrounds and who speak different languages.

- Approximately 50% of those accessing or benefitting from the LEAP programme directly are children (6,966)

- 87% of children were below 4 years old at the time of registration, placing them in LEAP’s target cohort.

- 45% of children across all ages interacting with LEAP services are from the LEAP area, compared to 45% of parents and carers, and 44% of children aged 0-3.

- Mothers account for 87% of parents and carers accessing the LEAP programme, with only 7% of parents and carers being fathers.

- The ethnic diversity of individuals attending the programme is similar to that of the wider Lambeth population.

5.1 Why does outreach matter?

LEAP invests significantly in outreach and referral efforts for a number of reasons.

First, the more people who engage with LEAP services, the greater the positive impact the programme has on the community in our target areas. Reaching the right people is also essential to LEAP’s efforts to improve child development outcomes – not everyone would benefit equally from engaging with services. With this in mind, several services across the LEAP programme have eligibility criteria, specifying a target group for their programme, while some services are universal (open to all) (see Appendix 1).

All services also aim to reach and engage with individuals who come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and to encourage engagement across other services on offer at LEAP, where families are eligible.

5.2 Why do we collect data on who our services are reaching?

Collecting data on who accesses LEAP services allows us to understand whether services are achieving their aims to reach relevant groups in the local community.

Where possible, programme data is compared against population level data from relevant sources to identify gaps and understand more about the level of diversity across Lambeth.

Collecting data also allows us to understand more about the families LEAP services support, and to consider additional support that families may need. Ultimately, it helps to ensure services are developed and adapted to be as inclusive as possible.

5.3 How does LEAP collect outreach data?

When signing up to a service for the first time, families are asked to complete a short registration form which collects demographic information about children and parents or caregivers.

The data presented below summarises demographic information for children and adults accessing services across the programme between 16th October 2015 and 31st March 2022. It excludes data from the Family Partnership Model, Children’s Centres which were not part of the capital works programme, and community engagement activities. Four Children’s Centres are included for dates after 2020 Q1 due to the capital works programme. The use of a unique identifier from LEAP’s data platform means individuals are represented once in the demographic data below, although they may have accessed more than one service. For more detail on this, please see Appendix 4.

What should I consider when looking at demographic data?

Registration forms have been adapted over time to ensure services are collecting similar types of information, in a similar way where possible. This means some information which may not have been collected at the start of LEAP is now being collected.

In addition, although practitioners encourage full completion of registration forms, there are sometimes gaps in data. Validation rules set on LEAPs data integration platform aim to minimise inaccuracies due to data entry, however such inaccuracies are still possible. Due to gaps in data, numbers might not match up across fields (for example if an age is not recorded accurately for a child).

Data where attendance about an appointment has not been recorded or updated has not been included.

5.4 Who has accessed LEAP services?

LEAP has so far engaged over 14,200 individuals, including 6,966 children and 7,239 adults. These individuals are representative of the diversity within LEAP’s target area, including people from different ethnic backgrounds, countries of origin, and who speak different languages.

5.5 Access by family role

Table 1: Breakdown of individuals accessing services by their position in the family

| Participant’s Role | Number of Participants | Proportion of Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | 0-3 years old | 6038 | 87% |

| 4-17 years old* | 768 | 11% | |

| Age unknown | 160 | 2% | |

| Total Children | 6966 | 100% | |

| Adults | Fathers | 483 | 7% |

| Mothers** | 6288 | 87% | |

| Other Primary Caregiver | 24 | <1% | |

| Other Family Member | 404 | 6% | |

| Other | 29 | <1% | |

| Childminder | 11 | <1% | |

| Total Adults | 7239 | 100% |

**Mothers are inclusive of pregnant women

Almost 50% of the individuals accessing the LEAP programme are children. Some services also provide data for children who are indirectly benefitting from the service and may be attending creche for the duration of the session. Of the children interacting with LEAP services, 83% were under the age of 4 at registration, and therefore within LEAP’s target cohort.

Mothers account for 87% of parents and carers while fathers account for only 7%. In some cases, parents and carers may be under the age of 18 but will be responsible for a young child accessing the programme, therefore will be included under parents and carers.

A note on family role terminology

Throughout this section we refer to individuals as ‘mothers’, ‘fathers’ and ‘pregnant women’. This reflects the options available on the most recent registration forms, which allow parents to select from ‘mother’, ‘father’ or ‘other primary carer’. Previous systems allowed for additional fields such as ‘Other family member’, ‘Other’ and ‘Childminder’, so for some sections these categories are also presented.

LEAP’s data collection system does not have a gender-neutral parent role and the registration form only includes ‘male’ and ‘female’ options. This is to maintain consistency throughout the programme and across services, but we recognise that these options may not capture the experiences of all our families. Services encourage inclusive approaches to gender, for example through sharing pronouns during introductions.

Why are so few fathers engaging with LEAP services?

The involvement of fathers in the early years is an important topic, both at LEAP and within the wider early years sector. There has been research on the benefits of engaging fathers during the early years, and about the importance of designing services to be inclusive for fathers, given that they are often under-represented.

Challenges engaging fathers in early years services include: a lack of consistency, with sessions aimed at dads usually being one offs, lack of representation on promotional materials and within the early years workforce, early years typically focussing on mothers, timings of sessions during weekdays, lack of substantial paternity leave, or understanding or shared parental leave. There is also a lack of spaces, WhatsApp and social network groups dedicated to fathers.

At LEAP, we ensure fathers’ voices are included and heard during community co-production sessions, and target recruitment for parent volunteer roles. We also try to increase engagement by organising dad’s sessions through our festival-model of engagement, ensuring dads are represented on promotional materials. We further enhance the local offer for dads by funding organisations that work with dads through the CoCreate fund.34

5.6 Access by area deprivation

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) measures relative levels of deprivation across England according to seven criteria (income, employment, health deprivation and disability, education, skills and training, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment).

Each neighbourhood (consisting of approximately 650 households)35 in England is given a score, then the neighbourhoods are all ranked. The final IMD score is based on this rank, and therefore reflects how deprived an area is relative to other areas. For the purposes of analysis we divide areas into five equal groups, with areas in group one being the most deprived, and areas in group five being the least deprived.

In 2019, 43% of neighbourhoods in the LEAP area were classified amongst the ‘most deprived’ 20% of neighbourhoods in England. LEAP also does not have any areas in the fourth or fifth groups (reflecting the relatively high levels of deprivation in the area).

Notably, in 2015 a significantly higher proportion of neighbourhoods in the LEAP area – 59% – were classified amongst the ‘most deprived’ 20% of neighbourhoods in England. However, as this is based on a relative ranking of neighbourhoods across England, this does not necessarily mean that the deprivation profile in the LEAP area has improved, but that it may have worsened to a greater extent in other areas across the country.

LEAP’s approach to measuring inequalities

LEAP’s intended impact of substantive improvement in outcomes for those children at greatest risk of poor outcomes articulates our commitment to reducing inequalities.

To measure inequalities LEAP tried to develop nuanced measures for Socioeconomic status (SES) indicators that were relevant to child outcomes. However, they proved challenging for services to collect routinely and didn’t feel directly relevant to services because the information being collected went beyond demographics.

In lieu of more nuanced indicators and given the poverty profile and diverse makeup of the local population, we have decided to focus on area deprivation and ethnicity as indicators for inequalities across outcomes and engagement data. We also look at language and country of origin although it is not a primary focus in this report.

5.7 Access by locality

Notably, significant proportions of certain groups (50% of children aged 0-3 and 48% of parents and carers) engaging with services are from outside LEAP’s target areas.

Table 2: Number of participants by locality

This includes families from outside of Lambeth. 1221 individuals engaging with LEAP services are from a borough other than Lambeth. Of those outside of Lambeth individuals are from neighbouring boroughs of Southwark (65%), Wandsworth (9%), and Lewisham (9%), and Croydon (8%). This could be due to the proximity of LEAP services in comparison to one’s home borough, particularly for those living near borders.

It is important to note that operational factors and changes made during the programme may also have influenced the number of families engaging with services who fall outside of the eligibility criteria. For example, some services extended their offer to non-LEAP families as they were starting up, or during periods of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| LEAP Area | Non-LEAP Lambeth | Non-LEAP Other Borough | Area Unknown | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children 0-3 | 2651 (44%) | 2537 (42%) | 536 (9%) | 314 (5%) | 6038 |

| Children 4+ | 463 (60%) | 238 (31%) | 39 (5%) | 28 (4%) | 666 |

| Parents and caregivers* | 3223 (45%) | 2905 (40%) | 627 (9%) | 447 (6%) | 7202 |

| Pregnant women | 1189 (83%) | 181 (12%) | 17 (1%) | 58 (4%) | 1443 |

Children’s location

44% of children aged 0-3 accessing the programme live in the LEAP area, and 60% of children aged 4 or above live in the LEAP area. Most children aged 0-17 (86%) accessing services are from Lambeth.

Pregnant women’s location

A total of 1,443 women were pregnant at some point during the time they accessed the LEAP programme, with 83% living in the LEAP area. This may be due to the eligibility criteria of services specifically supporting pregnant women. Pathways into maternity services means those services can contact all women who are booked for maternity care at Guys & St Thomas’ Hospitals (GSTT) or King’s College Hospital (KCH).

Parents and carer’s location

45% of parents and caregivers accessing the programme live in the LEAP area. 45% of mothers were from the LEAP area, and 4% of fathers were from the LEAP area.

5.8 Access by age

Data on age allows us to see the age at which children first register with the programme, and also the proportion of children over the age of 4 benefitting from the programme. We also collect the age of parents and carers to explore the average age and identify young families.

Children’s age

90% of children were between 0 and 3 years old at the time they registered with LEAP. Although the programme is aimed primarily at this age group, this may be explained by some services who have different age requirements or offer universal access. The Healthy Living Platform, for example, is open to families with at least one child under the age of 4.

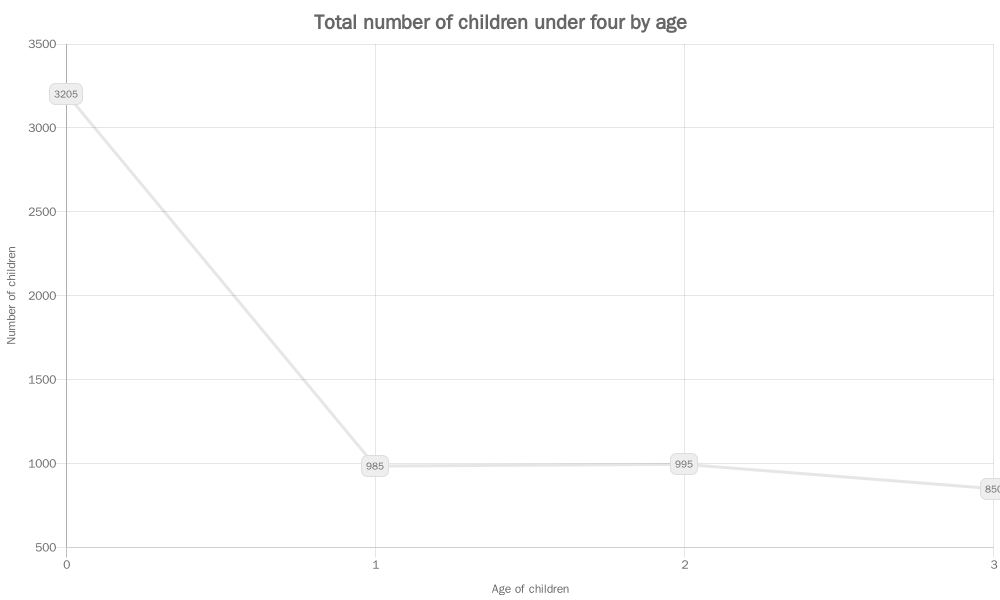

Figure 9 shows the proportion of children at each single year of age who have engaged with the programme. The programme had a higher proportion of children aged 0 at their registration date, perhaps reflecting that women tend to join LEAP during pregnancy, or that decisions to return to work after maternity leave results in fewer opportunities to engage with LEAP when children are over the age of one.

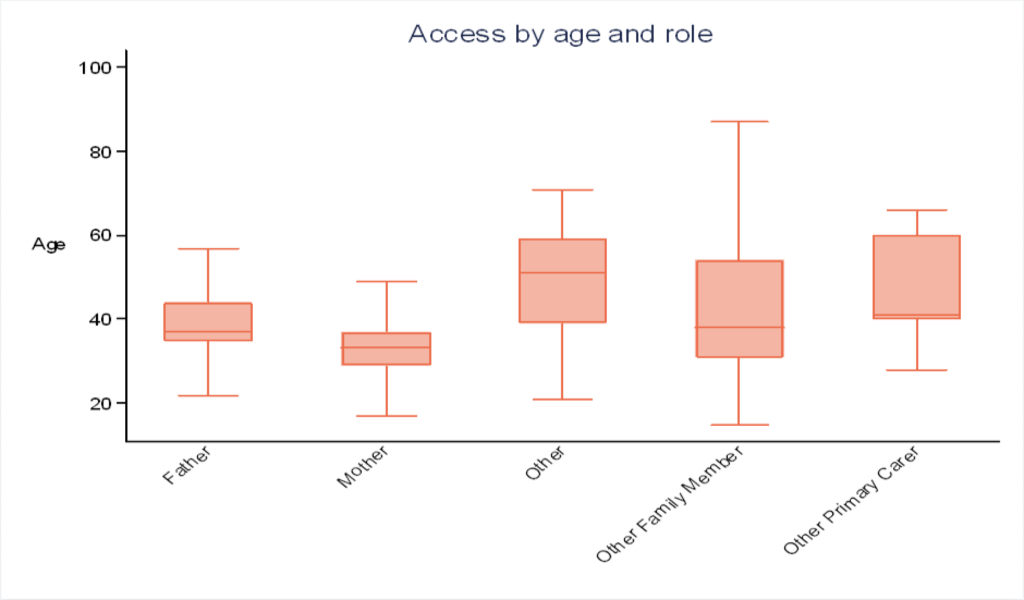

Parents and carers’ age

Ages for parents and carers engaging with the programme range between 13 and 102. The most common age group is 30 to 34 with 30% of parents or caregivers, followed by 35 to 39 with 29%.

1% of parents and carers are under the age of 17 at registration dates, with most of these (65%) living in the LEAP area.

Ages of mothers range from 14 to 55, while the average age of mothers attending is 33. Fewer than 1% of mothers engaging with the programme were under the age of 19 when starting the programme, which is broadly representative of the wider Lambeth population.

The most common age group for fathers is 35 to 39 at 31% and the average age of fathers is 37.

5.9 Access by ethnicity

By collecting data on ethnicity, we can explore whether there are differences in access, experiences and outcomes between different ethnic groups accessing our services. We can also make comparisons with ethnicity data on the wider population, allowing us to explore our reach. We can also consider, along with home language and Country of Birth, potential cultural practices, and ways to make service delivery as inclusive as possible.

The full ethnicity categories we use can be found on the example registration form in the appendices. This form is similar to the Lambeth children’s centre registration form36 and follows Office of National Statistics (ONS) guidelines where possible. When designing this form, one additional category (Black African – Somali) was added based on data available about who lives in the LEAP area.

Things to consider when looking at data on ethnicity

Ethnicity data is not always easy to collect. This may be due to families not wanting to share ethnicity data, particularly if they do not understand why data is being collected.

There may also be challenges with the way ethnicity is collected. Ethnicity is self-reported, and people may not always feel they fit into a box, or that ‘Other’ represents them well.

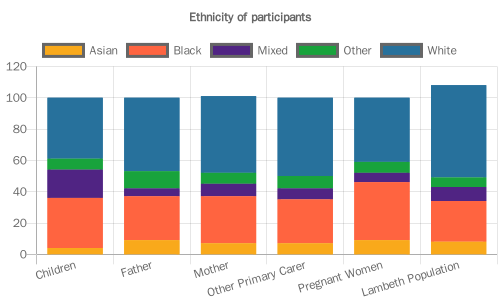

Figure 11 outlines the ethnicity breakdown of different groups engaging with LEAP services.

Children’s ethnicity

Ethnicity has been provided for 71% of children and is detailed in Figure 11. Of all the children engaging with the programme 40% are from a White background, followed by 31% from a Black background.

Pregnant women’s ethnicity

Figure 11 shows the ethnicity of women who have been pregnant at any point during their engagement with the LEAP programme. 90% of pregnant women provided their ethnicity while engaging with services. 41% of pregnant women are from a White background, and 43% are from a Black background. The breakdown of ethnicity is similar to the ethnicity breakdown of women accessing GSTT and KCH maternity booking service.37

Parents and carers’ ethnicity

Figure 11 shows the ethnicity of parents or carers. There is a higher proportion of adult family members from a White background, accounting for 38% of fathers, 49% of mothers and 50% of other family members.

The figure also includes ethnicity of the Lambeth population from the 2021 Census. Overall, the ethnicity profile of LEAP participants is comparable to that of the Lambeth population.

5.10 Access by sex and gender

All services collect data on individuals’ sex and gender. When collecting and referring to this information, for children we refer to sex, and adults we refer to gender.38

Limitations to data on adults’ gender

LEAP recognises that the current approach to collect data around sex and gender is not perfect or inclusive.

Though services aim to use inclusive language and be inclusive during service delivery, at present, registration forms only allow for individuals to select Male or Female when collecting data on gender. On top of this, though gender is not collected for some maternity services, it is currently a mandatory field on our integrated data platform, and as such is assumed to be ‘female’ for those engaging with maternity services.

Current developments within data systems at our partner NHS trusts (Guy’s and St Thomas’ and King’s College Hospital trusts) could allow for us to overcome this in the future by adapting the way data is collected for certain fields, allowing for more options.

Children’s sex

There is an even split between boys and girls accessing the programme overall, with 49% of all children under 18 recorded as female and 51% recorded as male. A similar split is observed when looking at the data for the LEAP area.

A lower proportion of boys compared to girls achieve expected levels of development at age 5, in the LEAP area, in Lambeth, and also at the national level.39 However, LEAP services that work directly with children do not specifically target boys because the services are implemented with all children in participating early years settings.

Parents and Carers’ gender

For parents and carers accessing LEAP services, 92% identify as female or are assumed to be female by maternity services who don’t collect data on gender, and 8% identify as male.

5.11 Special Educational Needs and Disability

LEAP aims to collect Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) information for children across the programme. This is particularly important to consider when exploring outcomes for children’s learning goals, and to ensure service delivery is as inclusive as possible.

Disability information has been recorded for 38% of parents and carers across the course of the programme, and for 60% of pregnant women.

Less than 1% of those who have disclosed their disability status have recorded ‘yes’ for both parents and carers, and pregnant women.

What should I consider when looking at SEND data?

Special Educational Needs and Disability data has not been collected consistently across the programme both over time, and across different services.

Additionally, although children are assessed against development goals as part of the Early Years Foundation Profile, the assessment process for a formal diagnosis can take several months. Data should therefore not necessarily be seen as presenting an accurate picture of service users.

5.12 Access by country of birth

Country of birth is collected as it helps to understand traditions and cultural practices, alongside ethnicity and language.

Children’s country of birth

Country of birth has been provided for approximately 56% of children. Out of those with a country stated, 94% of children were born in the United Kingdom. Appendix 7 shows the top four most common countries or areas of origin for children across the programme, accounting for 96% of children with a country noted.

Pregnant women’s country of origin

Country of origin has been provided for 79% of pregnant women, with 41% stating their country of origin is the United Kingdom. The remaining 59% are from other countries. The most common countries of origin are detailed in appendix 7. There are similarities between this data and the most common countries of origin reported from maternity booking data across GSTT and KCH37.

Parents and carers’ country of origin

50% of participants engaging in the programme have provided a country of origin. Out of those participants, 51% of parents and caregivers noted their country of origin as United Kingdom. The most common categories following the United Kingdom are Any Other Country (unspecified) accounting for 6% and Nigeria, Other African Country and Portugal, all accounting for 3% of parents and carers each. The most common countries of origin are set out in Appendix 6.

5.13 Access by home language

An individual’s home language is defined as the primary language that they speak at home with their family. Collecting home language allows us to understand potential translation needs, and the best way we can get our messages across to families.

What should I consider when looking at data on children’s home language?

There are gaps in home language data collected, with a language recorded for 52% of participants. The way data is currently collected on home language – by asking an individual to supply only one language – also means that we often have a limited understanding of their overall language capability.

For example, knowing an individual’s primary home language does not tell us whether they also have a good level of proficiency in English, so may not always be a useful indicator for whether they have translation needs. Similarly, it does not tell us if they have proficiency in languages other than English.

Languages with small numbers have also not been included in the tables. It is important to note the range of languages spoken goes beyond those listed, and families speaking these languages may not have regular access to translated materials of information should they need it.

Children’s home language

Home language has been provided for approximately 48% of children. Out of those with a language stated, 68% of children have a home language of English, and 32% speak a language other than English at home. Table 3 shows the most common home languages for children, across the programme.

Table 4 shows the most common languages for pregnant women where a language was recorded. Across the programme, 30% of pregnant women have speak a language other than English at home.

A similar observation is found in parents and carers. Table 5 shows the most common home languages for parents and carers, with 69% of parents and carers who provided language data speaking English at home, meaning 31% have English as an additional language.

Table 3: Most common home languages for children

| Home Language | Number of Children | Proportion of Children |

|---|---|---|

| English | 2,268 | 69% |

| Spanish | 174 | 5% |

| Other | 143 | 4% |

| Portuguese | 132 | 4% |

| Arabic | 105 | 3% |

| French | 83 | 3% |

| Somali | 56 | 2% |

Table 4: Most common languages for pregnant women

| Home Language | Number of Children | Proportion of Children |

|---|---|---|

| English | 850 | 70% |

| Spanish | 77 | 6% |

| Portuguese | 54 | 5% |

| Other | 53 | 4% |

| French | 26 | 2% |

Table 5: Most common languages for Parents and Carers

| Home Language | Number of Children | Proportion of Children |

|---|---|---|

| English | 2,835 | 69% |

| Spanish | 249 | 6% |

| Other | 177 | 4% |

| Portuguese | 151 | 4% |

| Arabic | 110 | 3% |

| French | 103 | 2% |

| Somali | 62 | 2% |

Next steps for evaluation and learning of our engagement:

- To explore the efficacy of efforts to engage more dads.

- To explore completeness for different fields e.g. home language, and reasons for different levels of completion.

- Find more ways to explore inequalities within the LEAP SMS data set.

5.14 Attendance at LEAP Services

Key findings

- During the programme, the number of session attendances has increased overall.

- The range of services accessed is one to 11 services.

- 84% of individuals have accessed one service.

- 15% of individuals have accessed between two and four services.

- 1% of individuals have accessed more than four services across the LEAP programme.

- Although the COVID-19 pandemic saw a decrease in attendance, services were able to adapt where they could and there was an increase in virtual delivery.

5.15 How many sessions have individuals attended?

Engagement data is analysed by the total number of attendances; therefore, individuals may be represented more than once across services and the programme.

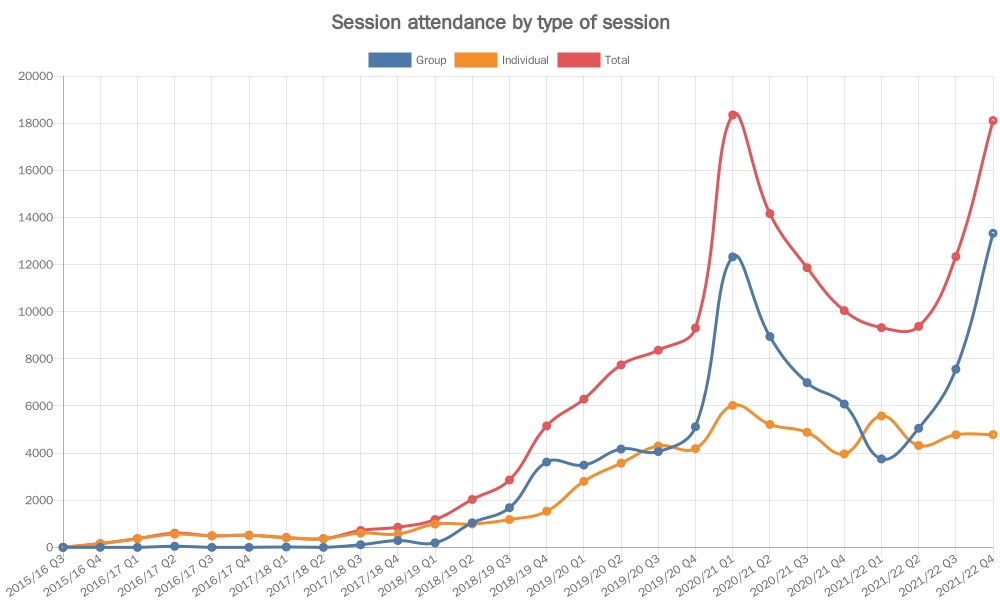

There has been a total of 63,113 attendances at individual sessions and 87,865 at group sessions across the LEAP programme.

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown and social distancing rules created a challenge for services to be delivered as expected, and adaptations were made across the programme where possible. Some activities were paused and then later resumed, some transitioned to a virtual delivery format, and in some cases LEAP sought to enhance or add to existing services; for example developing website activities.40

5.16 Group versus individual sessions

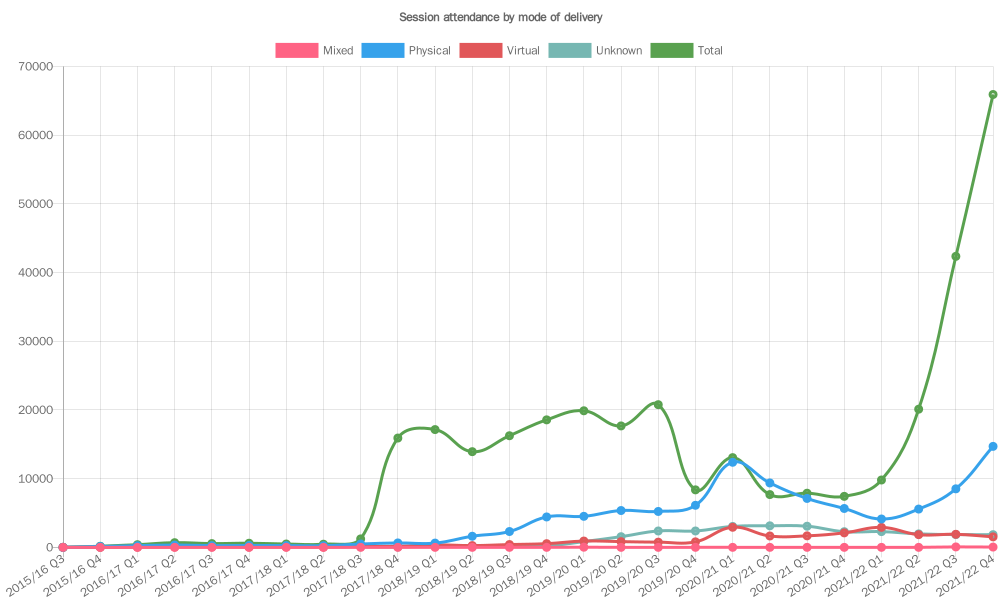

Figure 12 shows the number of group sessions, individual sessions and total number of sessions attended each quarter. There was a decrease in the number of attendances during 2019/20 Q4, reflecting the period of the first COVID-19 lockdown.

5.17 Online versus face-to-face sessions

64% of attendances were at sessions delivered face-to-face, while 16% of session attendances were virtual. Although some appointments were completed virtually prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of virtual session attendances increased during quarter 1 of 2020/21 (April 2020 – June 2020) following the first lockdown of the pandemic (Figure 13). The following quarters saw a reduced number of attendances compared to pre-pandemic levels, but attendance increased again during quarter 2 of 2021/22 (July 2021 – September 2021).

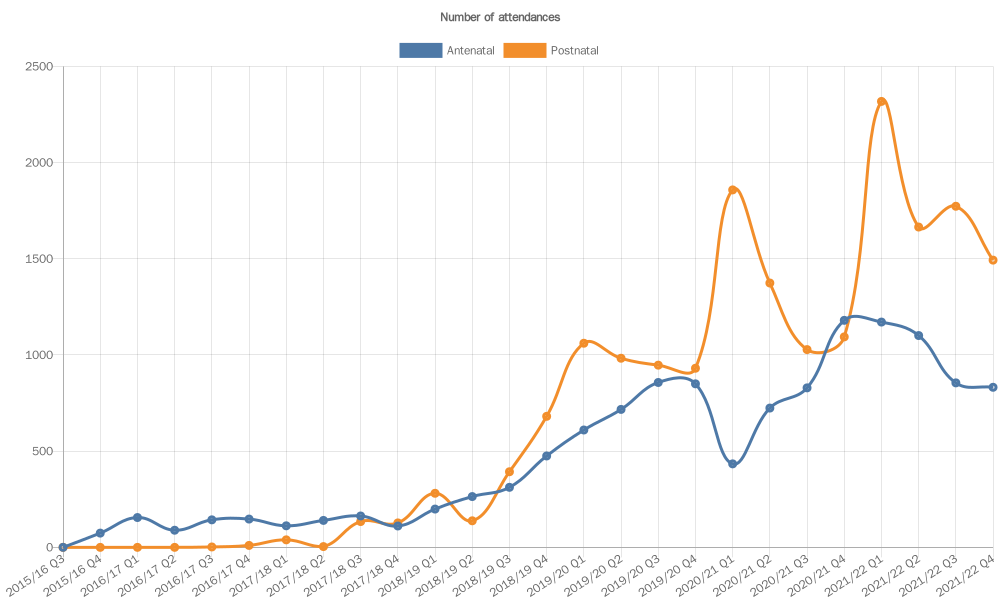

5.18 Antenatal vs Postnatal sessions

Figure 14 shows the number of attendances broken down by whether services are aimed at antenatal support. This allows us to see how the engagement of pregnant women and new parents has changed over time. In the early stages of the programme, there was a higher number of attendances for antenatal delivery, compared to postnatal. Quarter 3 of 2018/19 saw a shift, with a higher proportion of attendances for postnatal sessions. The number of individuals attending postnatal sessions began to increase in 2017/18 Q3, while attendance of antenatal services began increasing earlier in the programme (2016/17 Q1).

There was a drop in attendance at antenatal services during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic – 2021/21 Q1, but this began to increase again in the following quarter. In contrast, there was an increase in attendances at postnatal services during the start of the pandemic, but this dropped during 2020/21 Q2 before increasing again during 2020/21 Q4, suggesting there was still a need for support postnatally during the early stages of the pandemic. During the early stages of COVID-19, NHS staff delivering some services were redeployed, which influenced the number of sessions available for women antenatally. Additionally, there was limited evidence around the effects of COVID-19 on pregnant women and risks were unknown.

Next steps for evaluation and learning of our attendance:

- Explore trends in group session attendance.

- Explore reasons for different patterns of service attendance and why 80% of LEAP participants only attend one service.

6.0 Improving Early Child Health & Development

At the centre of LEAP’s Theory of Change are the outcomes that LEAP wants to achieve with children directly. LEAP aims to improve outcomes for children in three key areas: diet and nutrition; social and emotional development; and communication and language development.

6.1 Challenges in collecting early child health and development outcomes

Collecting outcomes for children in infancy and early childhood can be challenging. While diet and nutrition outcomes such as weight or dental caries can be physically measured, measuring communication and language, or social and emotional development, is more difficult. Infants and very young children may not be able to easily communicate their thoughts and feelings, and so outcomes must be observed or reported by someone who knows the child well.

Some LEAP services measure outcomes for children, and in this report we present data from PAIRS and Natural Thinkers on children’s social and emotional development. In future reporting we will also be able to present data on communication and language outcomes. Population-level indicators measured for all children in Lambeth provide another very useful source of information on LEAP children’s outcomes.

To date we have monitored these indicators to provide important context. Analysis of how these indicators have changed over time will be an important feature of LEAP’s summative evaluation work. In this report, we present some descriptive statistics on relevant indicators.

6.2 Population-level data on children’s outcomes

Several child outcome indicators are monitored at a population level, capturing data for both the LEAP area and across Lambeth. The indicators presented in Table 6 are monitored in line with some of the key childhood development outcomes we focus on. The indicators presented are generated using data from the most recent year available.

Using population-level outcome indicators

The LEAP area was selected based on local need, drawing on local sources of evidence including a set of population-level indicators spanning demographics, the wider determinants of health and each of the A Better Start outcome areas.41 The LEAP team continues to monitor and analyse many of these indicators to understand the ongoing context in which the programme operates.

Additionally, population-level outcome indicators can provide insight into the potential impact of LEAP services on the outcomes of a population, where service-level outcomes in a given area are unavailable or still in development.

While population-level outcome indicators are a valuable source of information and offer an alternative data source in lieu of direct participant data, there are limitations to using these indicators as proxy measures for service-level outcomes:

- We cannot identify LEAP participants within the wider population at this stage.

- Population-level outcome indicators may be more sensitive to detecting the impact of LEAP services with wider or more universal reach compared with more targeted services with very specific criteria which reach a smaller proportion of the population.

Children living in the LEAP area have poorer diet and nutrition outcomes compared to children in the rest of Lambeth

Being born with either low birth weight (Defined as a birth weight below 2,500 grams) or high birth weight (Defined as a birth weight above 4,000 grams) is associated with poorer outcomes. Low birth weight is associated with an increased risk of infant mortality, developmental problems and poorer health later in life.42 A high birth weight is associated with an increased risk of obesity, heart disease, and cancers later in life.43 44 45

Childhood obesity is associated with a higher chance of obesity, premature death, and disability in adulthood. During childhood, children with a higher BMI are also more likely to have breathing difficulties, hypertension, insulin resistance, and fractures.46 Tooth decay causes pain, infection, lack of sleep and time off school. In extreme cases children must have teeth extracted in hospital.47

Table 6: Population indicators of children’s diet and nutrition

| Indicator | LEAP Area | Lambeth |

|---|---|---|

| Rate of babies born with a high birth weight (2021) | 99 per 1,000 deliveries | 96 per 1,000 deliveries |

| Rate of babies born with a low birth weight (2021) | 42 per 1,000 deliveries | 36 per 1,000 deliveries |

| Percentage of overweight and obese at school entry (2020) | 26% | 23% |

| Percentage of overweight and obese at age 11 (2020) | 42% | 37% |

| Rate of hospital admissions for dental extractions in under 5s (2020) | 386 per 100,000 | 244 per 100,000 |

For all outcomes relating to diet and nutrition, LEAP children have poorer outcomes compared to Lambeth.48 49 50 For further comparisons and more data see LEAP’s data dashboard.51

Children in Lambeth are less likely to meet the expected level of development than nationally.

The Early Years Foundation Stage Profile (EYFSP)52 is used to assess the development of pupils in reception, measuring both personal, social, and emotional development, and communication and language development. Both are monitored for children living across Lambeth. National data are not available for 2019 but comparing data from 2018 shows that a smaller proportion of children from the LEAP area and across Lambeth achieved at least the expected levels of personal, social, and emotional and communication and language development compared with the England average.53 51

| Indicator | LEAP (2019) | Lambeth (2019) | England (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of 5-year-olds reaching at least expected level of communication and language development | 80% | 80% | 82% |

| Percentage of 5-year-olds reaching at least expected level of personal, social, and emotional development | 82% | 83% | 85% |

6.3 LEAP services targeting child level outcomes

Improved obstetric outcomes, including mode of birth and reduction in preterm delivery and stillbirth (Caseload Midwifery)

Improved diet and nutrition including reduced incidence of high or low birthweight, reduced incidence of high or low BMI, and fewer children with dental caries / decay (HLP, CAN, Oral Health)

Improved social and emotional development including age-appropriate self-management and self-control, secure attachment to a trusted caregiver, child mental health and wellbeing, and positive relationships (PAIRS)

Improved communication and language development including age-appropriate use of verbal and non-verbal communication, age-appropriate vocabulary comprehension, and listening and attention skills (Natural Thinkers, Speech and Language Therapy, Making it REAL, Sharing REAL With Parents and Supporting Babies’ Next Steps)

Further detail on the measurement tools being used to measure child-level outcomes can be found in the appendices or LEAP’s Practitioner Guide.30

6.4 Improved social and emotional development

Key findings: Improved personal social and emotional development

- Fewer children have observed difficulties with day-to-day activities after their families have attended the PAIRS One-to-One service.

- After receiving one-to-one support, family relationships improve and no families have disordered/dangerous relationships between parents and their infant or young child.

Parent-child relationships improve and children have fewer observed difficulties with day-to-day activities after receiving support from PAIRS One-to-One Service

The PAIRS One-to-One Service uses elements of the DC:0–5™ Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood (DC:0-5)54 to recognise mental health and developmental challenges in infants and young children and to monitor changes over the course of families’ attendance at the service (The full questionnaire contains six questions, but the PAIRS team only collect data for questions one, two and six).

The PAIRS clinician completes a questionnaire every 10th session, or every 3 months, depending on which occurs first, based on their observations of the family.

| Tool used | Timeframe | Sample size |

|---|---|---|

| DC:0-5 questionnaire | July 2017 – Jan 2022 | PAIRS One-to-One: 28 55 |

The DC:0–5 defines ‘relationship-specific disorders of early childhood’. A relationship-specific disorder is determined when ‘the infant/child exhibits a persistent emotional or behavioural disturbance in the context of one particular relationship with a caregiver’.56 PAIRS clinicians use these criteria to identify and record observable difficulties in each infant.

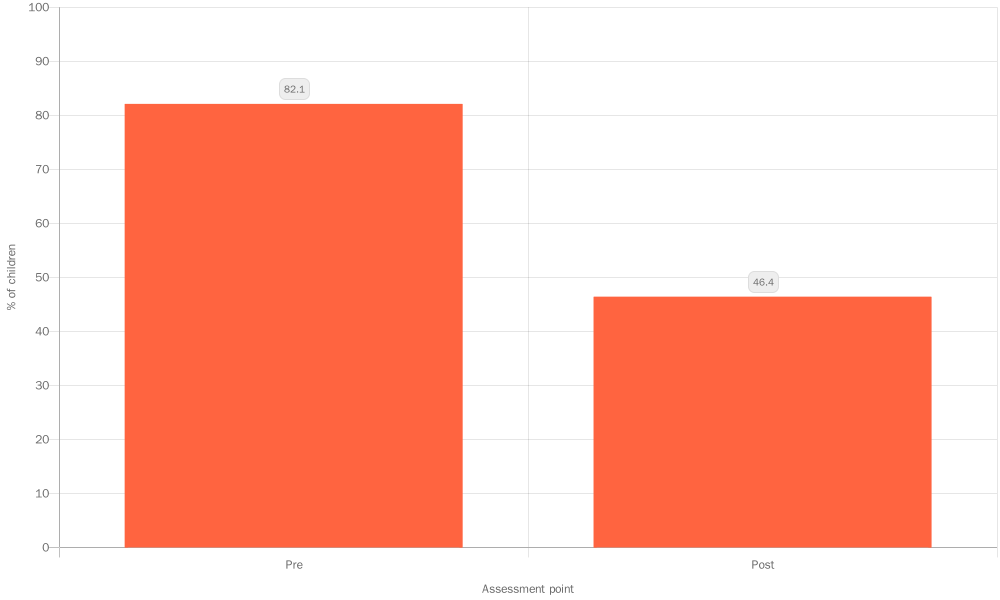

Observable difficulties were reported for 82% of children start of the service, reducing to 46% of children at the last assessment recorded for them, suggesting that engagement with PAIRS One-to-One has improved behaviour57.

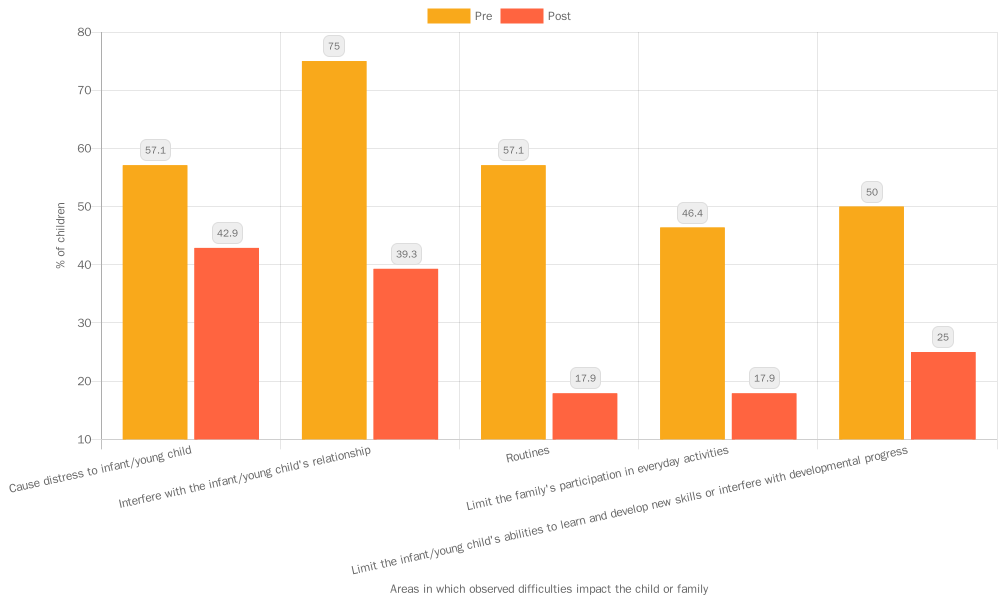

Clinicians also report how these difficulties impact the child or family (Figure 16). Before receiving support, three-quarters of children had difficulties impacting their relationships, and more than half had difficulties causing them distress or negatively impacting family routines. After receiving support, children were less likely to be experiencing difficulties across all areas. The impact on family life day-to-day was much lower, though clinicians still observed distressing difficulties for 43% of children.

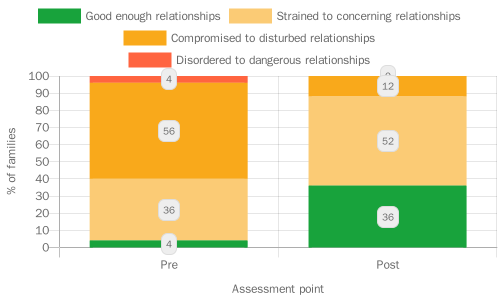

Clinicians also assess the overall level of relationship functioning between a child and their parent using the DC:0–5 ‘levels of adaptive functioning’ scale which takes into account aspects of caregiving and the child’s contribution to the relationship. The relationship can be categorised in terms of four levels of adaptive functioning. Level 1 is ‘good enough’ relationships that are not of clinical concern, level 2 is ‘strained to concerning’ relationships, level 3 is ‘compromised to disturbed’, and level 4 is ‘disordered to dangerous’ relationships. The proportion of families with ‘good enough’ relationships increased from just 4% to 36% (Figure 17). After receiving support from the service, no families had disordered/dangerous relationships.

6.5 Improved child mental health and wellbeing

Key findings: Improved child mental health and wellbeing

After taking part in the Natural Thinkers programme, children had higher levels of wellbeing and were more engaged in activities in their early years setting.

| Tool used | Timeframe | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Leuven Scale | November 2021 – July 2022 | 147 children 58 |

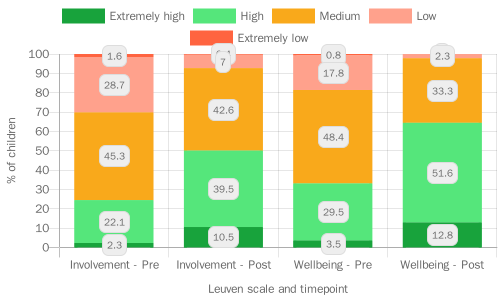

Practitioners in Natural Thinkers settings use the Leuven tool59 to observe and record children in their settings. The Leuven tool focusses on two indicators: wellbeing and involvement. It is a 5-point scale ranging from extremely low to extremely high. The wellbeing indicator measures the emotional wellbeing of children. The involvement indicator measures the engagement levels of children in particular tasks.

Children in Natural Thinkers settings had better levels of engagement with activities at the end of the academic year compared to the beginning

Around a third (31%) of children were rated as having extremely low or low levels of engagement on their first assessment, compared with 7% at their last assessment. There was an increase in the proportion of children who were rated as having high or extremely high levels of involvement from 24% at their first assessment to 50% at their last assessment (Figure 24). This shows that children are better able to engage with activities at the end of the year.