An Evaluation of the Maternity Vulnerability Assessment Tool (MatVAT)

Dr Juliet Rayment, Independent Research Consultant, November 2022

An Evaluation of the Maternity Vulnerability Assessment Tool (MatVAT)

1.0 Executive summary

1.1 Background

The Maternity Vulnerability Assessment Tool (MatVAT) was developed in 2018-19 as a bespoke, holistic tool for midwives to measure vulnerability in pregnant women and birthing people, and during the early postnatal period.

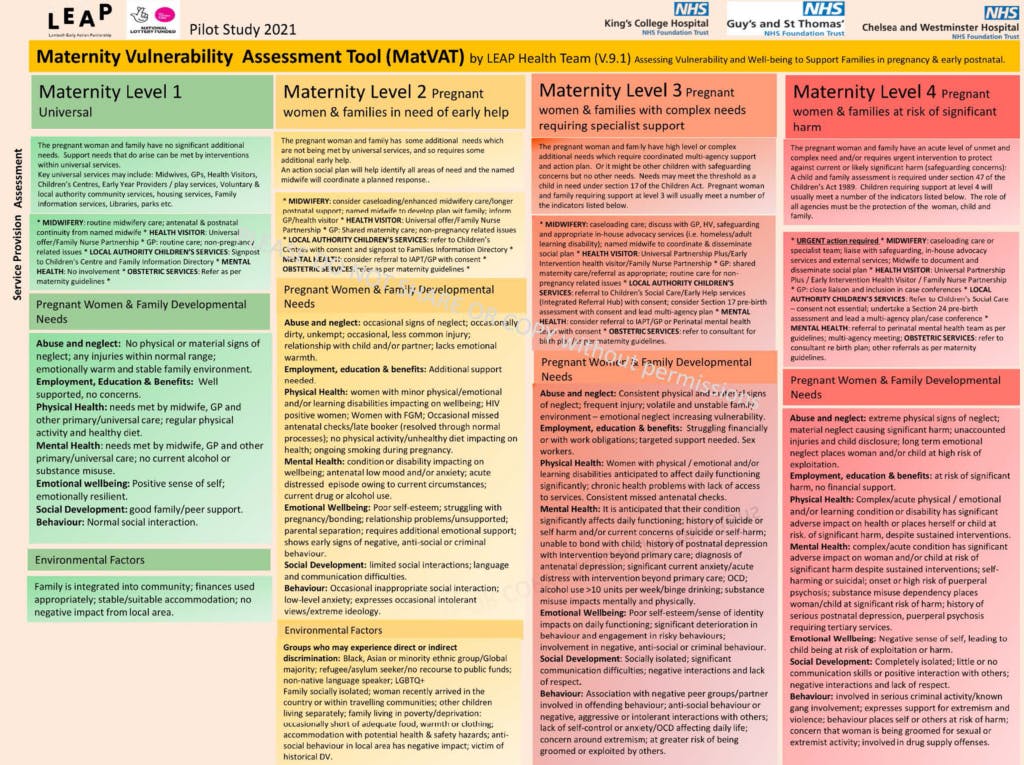

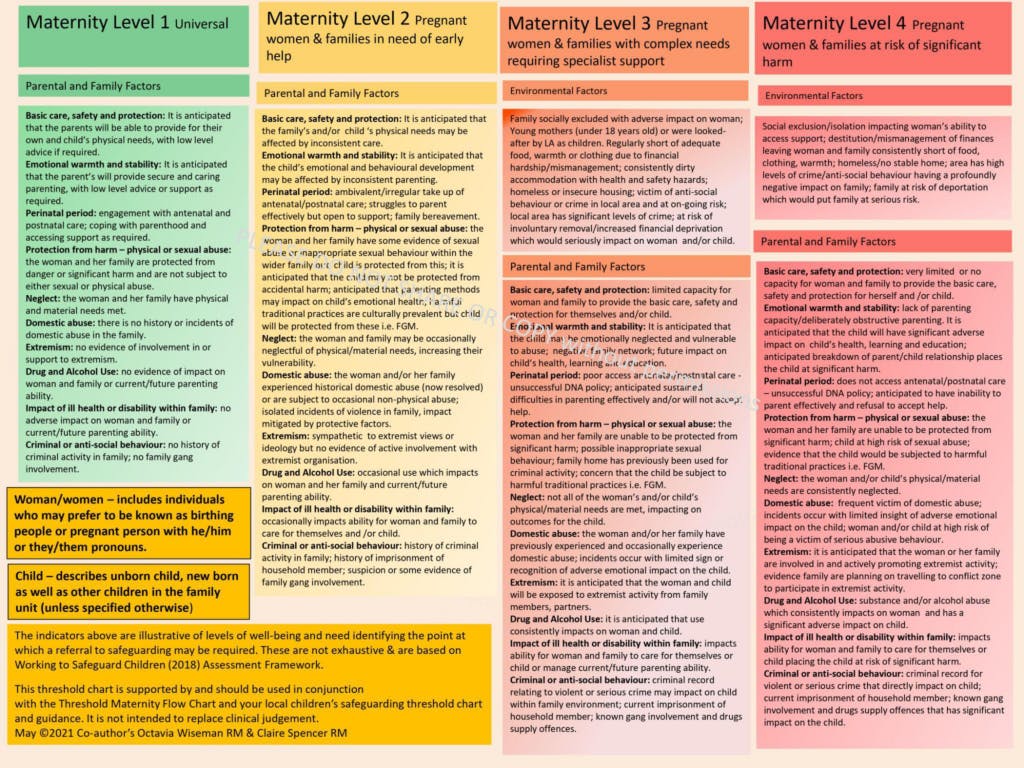

MatVAT is an A3 document with two parts:

- The first part acts as a threshold document to support referrals for additional support for pregnant women, including three categories: Pregnant women and family developmental needs; Environmental Factors; Parental and Family Factors. Women are then categorised as Level 1, 2, 3 or 4, coloured green, yellow, amber and red respectively.

- The second part of the document is a care planning guide listing possible sources of support for a woman at each level. An accompanying reference sheet has contact details for local support services that can be developed by individual maternity services about their own local resources.

1.2 Original aims of the evaluation

- To explore the feasibility of MatVAT in the context of routine community maternity care and its potential for roll out to other services.

- To explore whether midwives perceive the MatVAT to support improved care for women (i.e. triggering an increase in early referrals), an increase in midwives’ confidence in their own practice, and improved interprofessional communication. Negative perceptions will also be explored.

- To establish the internal validity of MatVAT by assessing how far it is used consistently by different health professionals.

These aims were amended in 2021 in response to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on participation in the project. Aim 3 was removed and the protocol was adjusted as follows.

1.3 Protocol

- Training: Community midwives in two teams (one traditional; one caseloading) from each site would be trained by the LEAP health team to use MatVAT.

- Choice: The Trust were free to use the tool in whatever way they found most useful.

- Interviews: Community midwives and any other relevant stakeholders would be invited to a short telephone/online interview.

- Routine data: Anonymised routine patient data would be collected for all women booked by the now four teams (one caseloading, one traditional per site) as per the original protocol.

1.4 Methods

Written feedback from training session participants

Observation of one online training session

Four discussion groups and one 1:1 interview with community midwives, specialist

Safeguarding Midwives and members of the project steering group

Minutes from 24 project meetings

Electronic Patient Record data (Site 1), June 2022

1.5 Findings

Current challenges

- Relying on ‘gut feeling’ to assess vulnerability introduces inconsistency;

- Existing informal systems to flag concerns on IT systems do not distinguish levels of need;

- Articulating intuitive concerns to others can be difficult;

- The system relies heavily on Safeguarding Midwives as the ‘safety net’ and to uphold thresholds for internal triage;

- Understandable caution around safeguarding can result in inappropriate escalation for some women;

- A lack of clear pathways for women who are socially complex, but who do not reach thresholds for safeguarding or mental health referrals.

Key findings

Intended Impact 1

When guided by the MatVAT, midwives feel more confident asking women and their families questions formally and acting on their intuition

- MatVAT has value as an internal threshold document for referral to Multidisciplinary Team meetings and specialist pathways, as well as communication with external agencies.

- MatVAT supported midwives to check their intuitive response and to facilitate joint decision-making.

- MatVAT has potential to support inexperienced or cautious midwives to make decisions about safeguarding.

Intended Impact 2

Midwives have increased understanding of primary health and care professionals’ systems (4-tier and Community/Universal, Targeted and Specialist) for assessing vulnerability and can ‘speak the same language’, improving communication between the primary care team (Health Visitor/GP/Midwife) and beyond.

- There is potential for conflict between MatVAT and other safeguarding threshold documents for some specialist safeguarding midwives who regularly work with different Local Authority thresholds;

- MatVAT offered consistency in internal thresholds;

- MatVAT supported midwives to escalate concerning cases back to Local Authorities.

Intended Impact 3

Midwives’ increased awareness of local support services in place for vulnerable women, (including the LEAP offer) will help them plan early intervention especially at levels 2-3.

- MatVAT can act as a prompt for midwives of possible referrals in response to Level 2 or 3;

- MatVAT may have less value for caseloading midwives than for those working in traditional clinics.

Intended Impact 4

Midwives and managers can formally quantify the complexity of their caseloads

- There is potential for MatVAT to be valuable in quantifying the demands of team caseloads to ensure even distribution of cases and to compare acuity between teams.

1.6 Factors affecting the use of MatVAT

Integration with IT systems

- MatVAT requires full integration with IT systems

- MatVAT should be positioned in a prominent place on the system (i.e. be a required data point) and require as little as possible in additional data input

- There is an appetite for automating some elements of MatVAT

Training

- There appeared to be some misunderstandings of the intended use of the tool amongst those who had not been trained and this showed the importance of training to its success

- Using MatVAT requires a level of comfort with complexity and ambiguity that may be at odds with conventional ways of working in the NHS

Format and layout

- Four tier structure, familiar RAG colours, quick tool a useful reminder

- Perceived as wordy

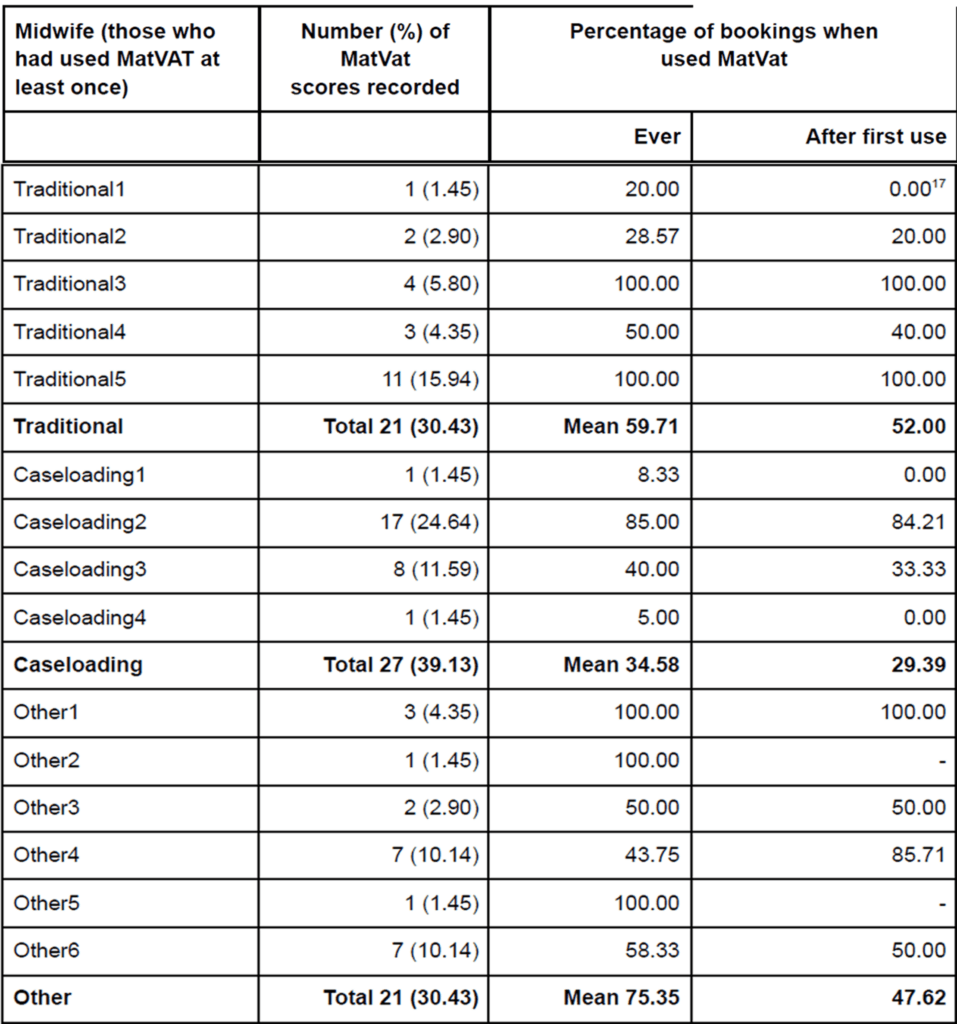

1.7 How was MatVAT used? Key figures April-June 2022

In Site 1 there were 2112 booking appointments in total between April and June 2022, of which 69 (3.3%) had a MatVat score recorded.

105 booking appointments were done during the period by 9 midwives who were participating in the pilot. Of these booking appointments, 46 (44%) included a MatVAT score.

Fifteen midwives (8.2%) used the MatVat tool at least once (between 1 and 17 times).

The midwives who used the tool at least once did so in a high percentage of their bookings (mean = 59.3%). After they had used the MatVat tool for the first time, midwives went on to use it in an average of 51.0% of their subsequent bookings.

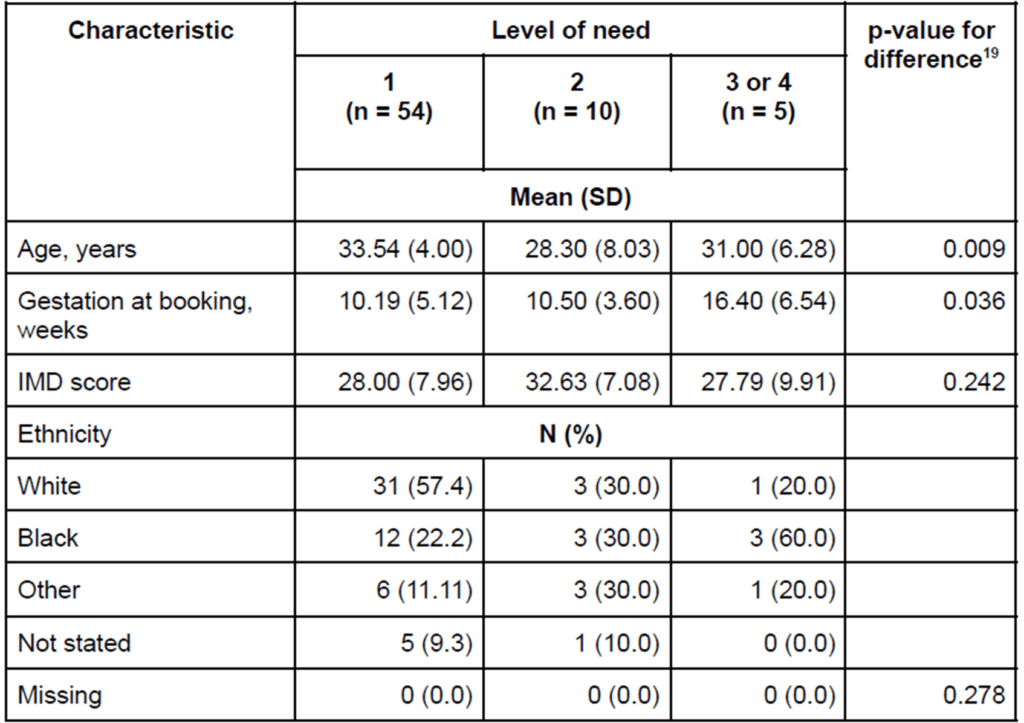

1.8 Which women received a MatVAT score?

Those women with a score (n=69) were assessed at the following levels:

- 78% at Level 1 (low social complexity)

- 14% at Level 2

- 4% at Level 3

- 3% at Level 4 (very high social complexity)

Their deprivation scores and ethnicity were similar across all levels of need. However, those that were categorised as 2 or higher tended to be younger and have later gestation at booking than those that were categorised as 1. In particular, those categorised as 3 or 4 booked 6 weeks later on average than those who were categorised as 1 or 2.

1.9 Summary of recommendations

The recommendations have focussed on the implications for future scale up and are summarised here. The full analysis is in the main report:

Liaison with partners and collaborators

- Liaise with Local Authority Safeguarding Boards in the future development of MatVAT to ensure an independent role for MatVAT away from LA thresholds

- Ensure that the relevant Local Authority agencies, Health Visitors, GPs and all midwifery teams are familiar with MatVAT

Implementation

- Consider other potential uses for MatVAT in future marketing and roll out

- Any Trusts that adopt MatVAT should ensure widespread roll out throughout their services, to provide continuity of use and to embed it within internal referral processes

- Future work could focus on providing MatVAT for those working in traditional clinics to support communication between many health professionals working with one woman

Training

- Ensure clear communication with Trusts and frontline staff about the practicalities of implementing MatVAT, including widespread training

- Develop sustainable, scalable training in the use of MatVAT as part of any future roll out

- Training in MatVAT could support newly qualified midwives’ confidence in working with safeguarding

- If a wider roll out goes ahead, consider implementing training into pre-registration or preceptorship courses, or in CPD/re-accreditation requirements to ensure widespread familiarity

Integration with IT systems

- Some automation of the tool would be valuable – for example for a system to automatically aggregate social information into one field along with the MatVAT score to avoid midwives duplicating information to record the reasons for their score

- LEAP should work with IT system developers to ensure the integration of MatVAT in the most commonly used NHS systems (e.g. Badgernet, Serner, EPIC)

Format and layout

- If MatVAT continues to be a paper document, LEAP could consider referring to it as something other than a ‘tool’ as for some, this implies an automated, electronic process

- Consider ways to reduce the amount of text on the main page or simplify the layout

- Continue the use of RAG colours and the four tier structure

2.0 Main Report (Introduction and background)

The Maternity Vulnerability Assessment Tool (MatVAT) was developed in 2018-19 as a bespoke, holistic tool for midwives to measure vulnerability in pregnant women and birthing people, and during the early postnatal period.

MatVAT was developed with the aim of enhancing interprofessional communication, and in recognition of the fact that safeguarding is an essential element of any framework.

2.1 Why is social vulnerability important in pregnancy and early parenthood?

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have been shown to increase the risk of adverse long-term health and social outcomes, including the parenting abilities of those affected1. In 2019, the Children’s Commissioner identified 2.3 million children in England who could be classed as ‘vulnerable’, potentially putting them at risk of long term negative impacts.

The Social Exclusion Task Force2 concluded that there is evidence of ‘a clear relationship between the number of parent-based disadvantages and a range of adverse outcomes for children’ and that identifying women and their families early offers the benefits of early intervention.

It is well established that women with multiple vulnerabilities are more likely to die in the perinatal period than others3. Interventions, such as those described in the Better Births report4 and the NHS Long Term Plan5 focus on the importance of personalised care and working across boundaries with a focus on the most vulnerable.

Previous evaluation of the Family Nurse Partnership programme and the Sure Start programmes have shown the benefits of these types of early intervention, especially where interventions are targeted. The Sure Start programme has had significant benefits for children’s health, preventing hospitalisations throughout primary school. But these benefits are only felt in the most disadvantaged areas6.

2.2 Defining and measuring social vulnerability

Despite the attention given to identifying and addressing social vulnerability, there is no clear, consistent definition of ‘vulnerability’ that is used within different disciplines and their policies or research.

In their guideline on ‘Pregnancy with complex social factors’ (2010), NICE do not give an exhaustive list of vulnerabilities, instead using four categories as exemplars, which reflect the groups of women who may be offered additional support in the maternity services:

- women who misuse substances (alcohol and/or drugs)

- women who are recent migrants, asylum seekers or refugees, or who have difficulty reading or speaking English

- young women aged under 20

- women who experience domestic abuse.

The lack of clarity on what ‘counts as vulnerable’ has the potential to lead to inconsistencies in the way that practitioners assess vulnerability. Without clear frameworks and guidance, practitioners’ understanding of vulnerability and its impact can easily be influenced by social stigma and by their own (unacknowledged) bias or prejudices.

2.3 Assessing social vulnerability

In 1995, the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) introduced the regular use of 4-tier models to assess and categorise social vulnerability. This multi-agency approach to identifying vulnerability and support safeguarding was integrated into Every Child Matters in 2003 and the 2004 Children Act.

Following the publication of ‘Every Child Matters’7, the 4-tier model was widely adopted by practitioners including social workers, GPs and Children’s Centre outreach workers. A similar, 3-tier programme, based on the principles of progressive universalism, has since also been in regular use by Health Visitors, incorporating ‘Universal, Universal Partnership and Universal Partnership Plus’ vulnerability assessment tool (U, UP, UPP). This has recently been updated to ‘Universal, Targeted and Specialist’.

A review of the child protection system in England8 recommended a move away from prescription and compliance using regulation towards one which supported professionals’ analytic and decision-making skills. Most threshold documents used to assess and categorise women, children and families according to social vulnerabilities use this kind of 4-tier system, corresponding to universal, ‘children in need of early help’, ‘children in need of targeted support’ and ‘children at risk’, or similar.

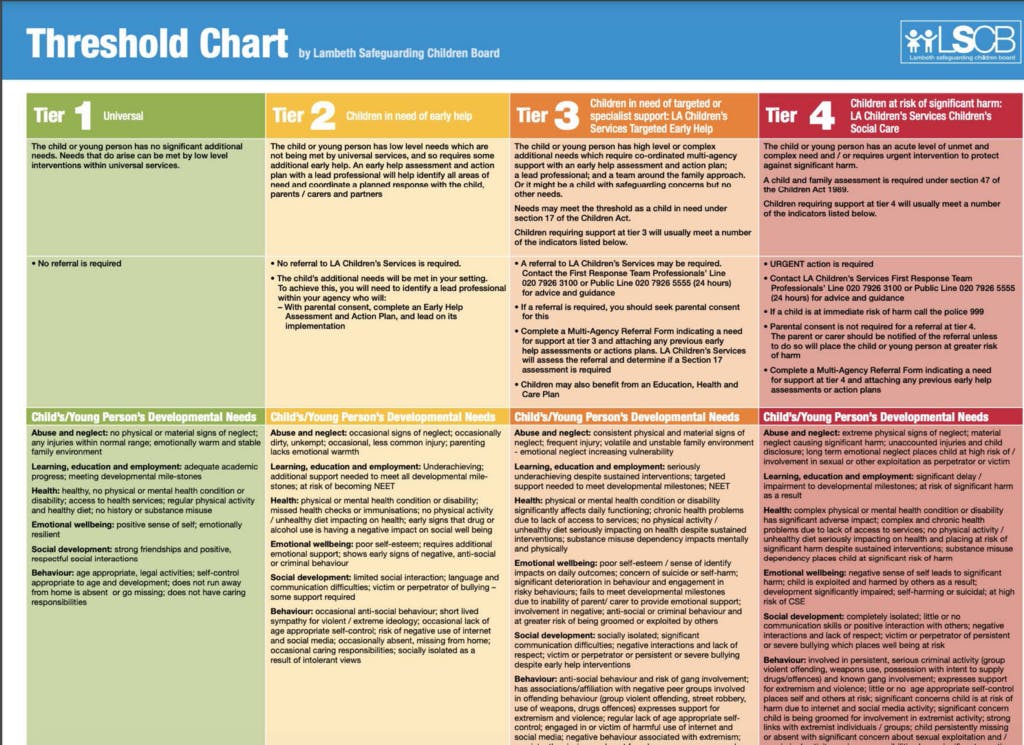

As an example, the Lambeth Threshold Chart9 uses these 4-tiers over three different assessment areas: Child’s/Young Person’s Developmental Needs, Environmental Factors and Parental and Family Factors. These existing 3-tier and 4-tier programmes have a focus on directly safeguarding the child, which makes them difficult to utilise in an antenatal care setting, where interventions are identified and implemented with parents. They also focus on much broader time periods than those covered by maternity services (i.e. 0-5 years for Health Visiting thresholds and 0-18 years for safeguarding thresholds). Some of them do attempt to take into account the needs of pregnancy.

The London Safeguarding Children Partnership includes pregnancy in it’s ‘Threshold Document: Continuum of Help and Support’10, including parent/carers’ access to ante- and postnatal care, their postnatal emotional wellbeing and their capacity to respond to the basic needs of a baby as part of the assessment of ‘Parental and Family Factors’.

The Lambeth Safeguarding Children Partnership ‘Multi-Agency Pre-Birth Assessment Flow Chart’ guides midwives through actions taken in response to an assessment of vulnerabilities during pregnancy, but does not include criteria for allocation to tiers.

2.4 Assessment in maternity services: what currently happens

In practice, most midwives gather evidence using a range of questions at the booking appointment, including the Whooley Questions and GAD-2 which focus on mental health, as well as questions about domestic abuse and the women’s physical health and life circumstances. Midwives use their experience, professional expertise and ‘gut feeling’ to assimilate the answers to all the information they are given to develop a care pathway.

Why is this a problem?

MatVAT was developed in consultation with safeguarding, mental health leads in Lambeth, service users and two local Trusts. The LEAP Health Team11 approached the development of MatVAT in response to concerns by midwives on the health team that, unlike GPs and Health Visitors, midwives did not have an existing system for assessing and recording vulnerabilities. LEAP found that having no formal framework to assess maternal vulnerability meant midwives:

- May not consistently identify lower levels of vulnerability (Tier 2-3)

- Have no clear referral pathways for care planning for mild-moderate vulnerability

- Must rely on tacit knowledge which we describe as ‘gut instincts’ or proxy measures (e.g. immigration status, language needs, ethnicity, age), to measure the vulnerability of their population

- Don’t have a shared language to discuss vulnerable women with other disciplines, leading to poor interprofessional communication around assessment and referral

- Managers cannot quantify the vulnerability (and hence the needs) of the population they care for

For women, children and their families, having no formal framework to assess maternal vulnerability means they may be less likely to receive timely and appropriate preventative support.

3.0 What is MatVAT?

MatVAT is an A3 document with two parts. The first part acts as a threshold document to support referrals for additional support for pregnant women. A higher resolution image is available in Appendix 1.

Like other threshold documents, it includes a list of criteria for assessment across 4-tiers in three categories:

Pregnant women and family developmental needs

- Abuse and neglect

- Employment, Education and Benefits

- Physical Health

- Mental Health

- Emotional Wellbeing

- Social Development

- Behaviour

Environmental Factors

- Social isolation

- Migration status and language needs

- Membership of underserved communities

- Physical needs of the family

- Domestic or other violence

Parental and Family Factors

- Basic care, safety and protection

- Emotional warmth and stability

- Perinatal period

- Protection from harm – physical or sexual abuse

- Neglect

- Domestic abuse

- Extremism

- Drug and Alcohol Use

- Impact of ill health or disability within the family

- Criminal or anti-social behaviour

Women are then categorised as Level 1, 2, 3 or 4, coloured green, yellow, amber and red respectively.

The second part of the document is a care planning guide that references possible local sources of support for a woman at each level, including:

- What women and partners can do

- Midwifery

- Health Visitor

- GP

- Local Authority Children’s Services

- Mental Health

- Obstetric Services

There is also an accompanying reference sheet with contact details for local services that can be developed by individual maternity services about their own local resources.

How was MatVAT intended to be used?

MatVAT was intended to support midwives’ intuitive decision in response to already existing, routine questions asked at antenatal appointments (i.e. it was designed to minimise additional work by utilising existing information).

The document itself was meant only to be referred to directly in a complex case where a woman might fall between two Levels. It was intended to take a holistic, strengths-based approach, balancing risks with protective factors in families, and to prompt practitioners to work in partnership with service users.

It was not meant to be used prescriptively or quantitatively (i.e. counting how many vulnerabilities a woman might have). MatVAT was intended to be flexible and to be changed to fit with local safeguarding thresholds.

As with other tools, a safeguarding referral is triggered when a family is assessed at MatVAT Level 4, and may be relevant at Level 3. But in addition, one of the main purposes of MatVAT is to support the care of women with ‘low-grade’ vulnerability (those at Levels 2 and 3) who do not reach the threshold for social services or perinatal mental health referral but would benefit from preventative care and support to reduce escalation of risk.

4.0 Theory of Change

Before the start of this evaluation, the LEAP Health Team developed a working Theory of Change for MatVAT.

Context

- Different healthcare professions are using no or different tools to assess and measure social vulnerability across maternity and early years.

- The Health Team found that although midwives are good at identifying safeguarding cases (Tier-4), very few midwives were aware of existing vulnerability assessment tools outside of maternity.

- For women, children and their families, having no formal framework to assess maternal vulnerability means they’re less likely to receive timely and appropriate preventative support.

- To address this gap, the Health Team, in partnership with King’s College and Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital Trusts, designed and produced the Maternity Vulnerability Assessment Tool (MatVAT) in 2018/19 – a holistic tool to measure vulnerability in maternity.

Assumptions

- MatVAT will be acceptable to midwives.

- MatVAT will trigger more, and more appropriate, referrals at Level 2 & 3.

- The existing system can manage additional referrals.

- Pregnant women will welcome referrals and that these will lead to an improvement in outcomes for women and their families.

- Changes to services due to the Covid-19 pandemic and evidence of poorer outcomes for women from BAME groups increases the relevance of the MatVAT which will support the identification of vulnerability and the development of individualised plans.

Evidence

- No formal evaluation of existing tools (4-Tier; U, UP, UPP), was identified.

- Government-based policies identify the need for disciplines to undertake an assessment of vulnerability as evidence of the long-term impact of early trauma and complexity grows.12

- A growing body of evidence suggests that early intervention reduces the need for downstream acute services, with associated cost savings.2

- Supported by national and local maternity guidelines – NICE, NMC, RCM, KCH and GSTT

- Better Births – Using common thresholds for assessment of vulnerability across different services and Trusts fit in with the priorities for maternity care outlined in Better Births.13

5.0 Intended Impacts

The Theory of Change also included some intended impacts of MatVAT relating to three areas: midwives, the maternity/early years system and women and families.

These were developed through the LEAP Health Team’s initial Public Involvement work, which included a discussion group with women from the LEAP area. This report looks specifically at the impacts for midwives.

Midwives

- When guided by the MatVAT, midwives feel more confident asking women and their families questions formally and acting on their intuition.

- Midwives have increased understanding of other systems (4-tier and Universal/Targeted/Specialist) for assessing vulnerability and can ‘speak the same language’, improving communication between the primary care team (Health Visitor/GP/Midwives) and beyond.

- Midwives’ increased awareness of local support services in place for vulnerable women, (including the LEAP offer) will help them plan early intervention especially at levels 2-3.

- Midwives and managers can formally quantify the social complexity of their caseloads. This could feed into appropriate resource allocation.

Maternity/Early Years System

- Increased identification of lower level vulnerability in pregnancy and postnatal period.

- Increase in appropriate early intervention referrals/focus on preventing escalation of problems reduces the need for acute services.

- Being able to quantify vulnerability in different areas enables more appropriate allocation of resources across the early years system.

- Referral assessment pathways for serious mental illness and safeguarding continue to be effective.

Women and families

- Women perceive themselves and their families to be listened to and feel like they are receiving more individualised care.

- Women and families receive more appropriate signposting and referrals to services and support (e.g. CC, outreach, Better Start workers, early help, IAPT, GP)

- Women will take up referrals and benefit from improved support.

6.0 Methods

6.1 The pilot

The MatVAT pilot was designed to run for six months. Community midwives working in caseloading and traditional teams in three London NHS trusts were asked to use it during routine community midwifery care.

6.2 Aims of the evaluation

The evaluation of the tool would take place concurrently with the pilot within the three sites. Its original aim was:

To explore the feasibility of MatVAT in the context of routine community maternity care and its potential for roll out to other services. To explore whether midwives perceive the MatVAT to support improved care for women (i.e. triggering an increase in early referrals), an increase in midwives’ confidence in their own practice, and improved interprofessional communication. Negative perceptions will also be explored. To establish the internal validity of MatVAT by assessing how far it is used consistently by different health professionals.

6.3 Proposed methods

The project started in autumn 2020 during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. It was designed to be remote (to account for social distancing regulations and predictions of further waves of Covid in winter and spring 2020-21) and to demand as little as possible from frontline midwives. Three Trusts were chosen to participate in the pilot.

Two of these trusts cared for women within the LEAP area and had close links with LEAP. A third Trust was recruited and was intended to act as a ‘control’ to assess the success of implementation within an ‘unfamiliar’ trust and one without personal and professional links to the LEAP health team.

The original protocol was as follows:

- Community midwives in two teams (one traditional; one caseloading) from each site would be trained by the LEAP health team to use MatVAT.

- MatVAT-trained midwives would then be invited to join a WhatsApp group with colleagues within their Trust. The group would offer peer support and be asked to respond collectively to a small number of questions about their experience with the tool. The group would be deleted immediately following the end of the Pilot.

- The midwives would also be asked to send a voice memo of their experience of using the tool after a clinic.

- Community midwives in the two teams would be invited to attend one online discussion group with their peers to discuss their experience of MatVAT.

- Further one to one interviews would be carried out with a small number of midwifery managers and stakeholders at each site.

- A validation exercise required a small number of midwives, health visitors and GPs to assess a series of fictionalised case studies using MatVAT to test whether the tool was used consistently within and between professional groups.

- We planned to collect anonymised routine patient data for all women booked by the six teams (one caseloading, one traditional per site). This included the following, for all women booked across a one month period with these two teams:

- MatVAT score

- Demographic details (maternal age, gestational age at booking, IMD score, Ethnicity)

- The anonymised ID of the midwife taking the booking

For the same women at their 28 week appointment:

- MatVAT score

- The anonymised ID of the midwife

The MatVAT score for a new cohort of women booking for care at the same period that the original cohort had their 28 week appointments (to see if midwives continued to use MatVAT at booking appointments over time).

6.4 Background and context to the evaluation

This evaluation project was commissioned in October 2020 with an original end date of April 2021.

The years 2020-2022 have been some of the most demanding in the history of the NHS maternity services. The Covid-19 pandemic brought a rapid reorganisation of services, widespread staff absence and an increase in both social and clinical need. At the time this project was commissioned, the 2020 Covid-19 lockdowns and other social distancing regulations had halted most clinical research, creating backlogs in R&D approvals when research was permitted to restart.

Initial approval for this project was granted by the HRA in early January 2021, R&D approval was then granted by two sites in May 2021. The third site did not issue approval until March 2022, and so was excluded from the pilot and evaluation due to this delay.

Through 2020 and 2021, the workload in clinical settings was becoming increasingly intense. The social impact of the pandemic was especially marked within community services, with a rise in referrals to safeguarding, and a corresponding increase in Local Authority thresholds for referral to try and manage caseloads.

This social and clinical context had a significant impact on this project from the start. It became clear early on that the health system and the community midwives were struggling to engage with us, within the context that they were working. For some time, the regular project meetings with the Trusts had few or no midwives attending. No community midwives joined the WhatsApp group on invitation and very few responded to repeated email requests for short online/telephone interviews. Interventions from senior midwifery staff appeared to have little impact. Notes from the project meetings record these challenges:

(The LEAP health team midwife) reported that all (caseloading team) midwives have been trained and that all but four (traditional team) midwives have been trained, but that it has been a struggle for the midwives to find the time to undertake the training, and although feedback has been very positive, they appear to be struggling to prioritise implementing the tool. The stresses on services due to staffing issues are a major part in these challenges. The fact that the team leaders did not attend this meeting, and nor did (two senior midwifery staff who had accepted it), is symptomatic of these demands.

I don’t feel that staff have capacity to do more than get out of bed and put on some scrubs.

Unfortunately no clinicians from (either teams) present so no report about how implementation is going.

None of this was surprising considering the crisis they were, and continue, to be working within.

6.5 Actual methods used

The pilot and evaluation team recognised the pressures midwives were under and did not want to add to their workload. In November 2021 we adjusted the plans to try and reduce the burden on midwives, improve engagement and to help make any data collection feasible.

The revised protocol was as follows:

Training: Community midwives in two teams (one traditional; one caseloading) from each site would be trained by the LEAP health team to use MatVAT.

Choice: The Trust were free to use the tool in whatever way they found most useful.

Interviews: Community midwives and any other relevant stakeholders would be invited to a short telephone/online interview.

Routine data: Anonymised routine patient data would be collected for all women booked by the now four teams (one caseloading, one traditional per site) as per the original protocol.

The final dataset is significantly smaller than we had planned for, due to the ongoing difficulties in recruiting clinical staff to interviews and discussion groups and the fact that one site could not be included in the evaluation. Multiple interviews were not attended or attended so late they had to be cancelled; staff often did not respond to requests.

At Site 2, one of the participant teams was disbanded during the project. Site 2’s decision to use the tool outside of routine antenatal care is discussed further in the report. We did not have approvals to go to the site in person for data collection as this was impossible for most of the project period due to Covid restrictions.

Data reported here is taken from the following:

Written feedback from training session participants

Observation of one online training session

Four discussion groups and one 1:1 interview with community midwives, specialist Safeguarding Midwives and members of the project steering group

Minutes from 24 project meetings

Electronic Patient Record data (Site 1), June 2022

6.6 Limitations of reporting

Women’s perspectives

As MatVAT is a ‘behind the scenes’ tool for midwives, using routine questions, women using the maternity services should not be aware of any changes to their care.

MatVAT would simply change the way midwives categorise women in response to standard questions, conversations, assessments and disclosures throughout antenatal care. Because of this we made the decision not to include women’s perspectives on MatVAT in this evaluation and will not report on the Intended Impacts for women.

Women’s views fed into the initial development work undertaken by LEAP in 2018-19.

Midwives’ perspectives

The ongoing difficulties with implementing this project during a period of crisis and the low uptake of MatVAT in practice, means we do not have enough data to be able to reliably report on the quantitative Intended Impacts for the Maternity/Early Years Systems: for example the impact of MatVAT on referral incidence and quality. For this reason, this report focuses on the experiences of midwives.

The report here relies on the views of a small sample and caution should be taken in extrapolating the findings beyond this sample.

7.0 Findings

The findings are divided into four sections. The first part describes existing processes that the services used to assess vulnerability, before the introduction of MatVAT. The second part outlines the benefits and challenges for MatVAT against each of the four Intended Impacts for midwives, the third part presents the analysis of routine data on the use of MatVAT over a two month period and the fourth part looks at the factors that affected its everyday use.

7.1 Existing processes

Community midwives described existing processes for assessing social vulnerability as a combination of clinical expertise and intuition:

Usually we would meet the couple and then, as we work through the booking questionnaire, we would then make our own judgment call as to whether we needed to refer to social services or refer on to the perinatal mental health team, or, like this morning, refer on to female genital mutilation clinic.

These sorts of informal measures for assessing women’s needs were seen as effective, but they were supported by more formal ‘safety nets’, such as routinely emailing the Safeguarding Midwives for further advice about women they were concerned about.

Specialist Safeguarding Midwives described Community Midwives as often ‘scared of safeguarding’. Worries about inadvertently missing something important had an impact on the cases that reach second tier support within the Trust, as this Safeguarding Midwife described:

People become defensive because they’re not sure what to do, so they refer it to the safeguarding team – put her on the socially complex list to discuss at the meeting. We’re finding cases that would be green (MatVAT Level 1) in that meeting that shouldn’t really be there.

Teams had developed their own systems for flagging women who needed additional support. For example, at least one team used ‘flags’ within Badgernet, which would then highlight ‘social issues’ to other midwives who saw that woman. This system was reported to work well enough, except that it did not distinguish between different levels of need:

Amber flags can range from somebody who smoked cannabis at Uni to somebody who’s, you know, really high risk of, you know, harm.

Another team had historically developed an ongoing bespoke spreadsheet to keep a record of the women in their caseload, as they found Badgernet was not fit for their purposes, beyond a basic record-keeping tool. This was used to communicate between team members and as a way of checking that all follow up appointments and referrals had been made. At the time of the interview they recorded postcodes as a proxy for social deprivation in an effort to monitor the needs of their caseload and ensure an even spread amongst the team. (Notes from interview with Community Midwife, Site 1)

- Relying on ‘gut feeling’ to assess vulnerability introduces inconsistency in internal thresholds;

- Existing ‘flagging’ systems do not distinguish levels of need;

- Articulating intuitive concerns to others can be difficult;

- System relies heavily on Safeguarding Midwives as the ‘safety net’ and to uphold thresholds for internal triage;

- Understandable caution can result in inappropriate escalation for some women

7.2 Using MatVAT

Intended Impact 1

When guided by the MatVAT, midwives feel more confident asking women and their families questions formally and acting on their intuition.

Following the change in the project protocol in November 2021, both sites found new uses for the tool, which included booking assessments, but also internal triage into multidisciplinary case review meetings.

MatVAT was used by both Trusts to introduce structure and consistency around criteria in order to support the ‘gut feeling’ traditionally used to determine thresholds for safeguarding interventions. Both Community Midwives and specialist safeguarding midwives described using MatVAT to both question or confirm their intuition:

When I saw it (MatVAT) the other day when I then went away and looked at it, it was extremely helpful because the woman that I had just booked was really quite vulnerable. I was trying to assess her level of vulnerability, like you were saying, just based on your sort of like, well, experience isn’t it; and also you know, actually it was helpful from that point of view because I was like, actually, yes – she’s probably a higher level than I might have put her at actually. So that was really helpful.

There was some evidence that by formalising a midwife’s gut feeling, MatVAT facilitated joint decision-making about how to support a woman:

It’s really good for conversations between ourselves. It would be quick to do a referral but using the tool means you can record why you haven’t made a referral – we looked at MatVAT and this is why we haven’t done it’; it’s a sense-check.

There was a feeling that if it was widely embedded within community teams, that having set criteria would help to support cautious Community Midwives to make decisions about referral, before coming to the specialist safeguarding team:

It’s a training tool in itself. You start looking at this (MatVAT) and then you start thinking ‘oh we should do a referral for this’. It’s an aide memoire. Even if they don’t put a score, just getting used to the score and using the levels as something we need to be concerned about. People are interested in this and in safeguarding. People get scared of safeguarding that they might miss something, at the weekend when they’re not sure what to do. It’s useful in and of itself.

Key findings

- MatVAT has value as an internal threshold document for referral to MDT meetings and specialist pathways, as well as communication with external agencies.

- MatVAT supported midwives to check their intuitive response and to facilitate joint decision-making.

- MatVAT has potential to support inexperienced or cautious midwives to make decisions about safeguarding.

Recommendation

- Consider other potential uses for MatVAT in future marketing and roll out.

Intended Impact 2

Midwives have increased understanding of other systems (4-tier and U/UP/UPP) for assessing vulnerability and can ‘speak the same language’, improving communication between the primary care team (HV/GP/MW) and beyond.

Midwives in Site 2 were encouraged to use the score as part of their presentation of cases within MDT meetings. Uptake was extremely variable, depending on their team and their personal engagement with MatVAT – as most teams were not trained in MatVAT or part of this evaluation. Site 2 also saw potential for MatVAT to be used to triage women for caseloading care after the initial booking appointment:

I think at the moment, we’re missing lots. Because I think just everybody’s, like you said, everyone’s time, they perhaps don’t answer (ask) the right questions. So we’re going to start using it (MatVAT) for the criteria to go into that team (caseloading for vulnerable women) and I am going to use the two top tiers in there and just have that as the criteria.

Whilst staff at Site 1 saw the potential for MatVAT to help select women for their monthly meetings with the Safeguarding Supervisor, they did not adapt it for use in their MDT meetings because of the conflict between MatVAT and the local safeguarding thresholds. Others suggested that it might have use in other areas of the service in particular Maternity Triage or Maternity Assessment Units.

Whilst they had not yet implemented this, one community midwifery team in Site 1 spoke about the potential benefit for MatVAT to replace the use of ‘flags’ in Badgernet, in order to improve communication within the team:

If I was doing an appointment for you just for me to know what the MatVAT score is before I go in, before having to read all the history to get an idea, that would be really useful. Because it is more information having a score than it is just an amber flag, which actually could be for anything, you know(…). So this would be definitely more useful than the flag in that sense.

Intersection with other threshold documents

Local authority threshold documents lay out the criteria for families to be accepted for different levels of support. The details of the criteria differ for every Local Authority, but the documents are usually similar – providing four tiers (‘Universal’, ‘Child in need of early help’, ‘Child in need of targeted support’ and ‘Child at risk’ or similar), using the RAG colours of green, yellow, orange and red.

Visually, MatVAT was designed to reflect other threshold documents. It closely resembles the threshold document for the Lambeth Safeguarding Children Board, with the same 4-tier structure, colours and the same categories for assessment – Environmental factors, Parental and Family Factors – with Lambeth’s ‘Child’s/Young person’s Developmental Needs’ changed to ‘Pregnant women and family Developmental Needs’ in MatVAT. This was noted by a Safeguarding Midwife:

I said, “You’re showing me the threshold document for Lambeth,” and the only difference was the wording. So I think they changed ‘child’ to ‘baby’. It’s pretty much identical. So it’s not a new piece of work. I know it was new to them. (…) Their assessment was that midwives were not aware of the tiers, but the difficulty is that they’re different for different boroughs.

Discussions raised questions about whether there might be a tension between MatVAT and other threshold documents. One participant was concerned that any kind of cross-borough ‘threshold document’ would be unworkable:

They could use MatVAT for Lambeth, but not for any other borough. And as I say, we work with so many, it’s not feasible to say, ‘You have to use this document only,’ because they do need to consider the other documents.

Others disagreed – seeing MatVAT primarily as a tool that could offer a consistent approach to internal triage, without conflict with other thresholds.

Unlike the specialist Safeguarding midwives, the small number of community midwives we spoke to appeared to have little knowledge of Local Authority thresholds and did not use threshold documents as part of their day to day work. It is difficult to come to any firm conclusions based on our small sample, but it appears that the use of MatVAT as an internal triage tool, particularly by community midwives, does not necessarily conflict with threshold documents that are used to refer to Local Authority services by the specialist team.

Caution around safeguarding has likely been exacerbated by a reduction in support available from Local Authorities during the pandemic, leaving the maternity services with lead oversight of some more challenging cases:

Those cases that meet child protection thresholds are much, much higher… For example, there is a case that we’re currently dealing with where the mum has a significant history of psychiatric admissions, she has a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. She’s not engaging with the mental health team, she’s not sticking to her medication regime. She has a significant substance misuse issue with cocaine and increased alcohol levels within pregnancy (…) and Social Care wants to close the case. So this is the level of challenge we are having to… So the early help is very much being pushed to the side, dare I say.

As increasing numbers of cases were being declined by the Local Authorities, MatVAT could be used to support pushback and escalation. This was because MatVAT offered a consistent approach from the Trust, even within a very variable Local Authority landscape:

Some LAs are getting such complex cases through their doors now that their thresholds have gone up. If the Trust is using a consistent approach then it gives you ammunition to escalate it (…): “This has been assessed as a high risk red (Level 4) and we’re really concerned.

Key findings

- There is potential for conflict between MatVAT and other safeguarding threshold documents.

- MatVAT offered standardisation for internal Trust thresholds.

- MatVAT supports midwives to escalate concerning cases back to Local Authorities.

Recommendations

- Liaise with Local Authority Safeguarding Boards in the future development of MatVAT to ensure an independent role for MatVAT from LA thresholds.

- Ensure that the relevant Local Authority agencies, Health Visitors, GPs and all midwifery teams are familiar with MatVAT.

- Any Trusts that adopt MatVAT should ensure widespread roll out throughout their services, to provide continuity of use and to embed it within internal referral processes.

Intended Impact 3

Midwives’ increased awareness of local support services in place for vulnerable women, (including the LEAP offer) will help them plan early intervention especially at levels 2-3.

Specialist Safeguarding midwives saw MatVAT’s referral ‘checklist’ as particularly helpful to remind community midwives of next steps, beyond a referral to social services. A number of people described the ‘checklist’ as the most useful part of MatVAT:

I think a lot of the time what we’re finding, or I’m finding, day-to-day is that the expectation is midwives are CCing us into the referrals they’re sending so that we can audit the quality of them and just keep a track of the cases that are coming through. And quite often, a lot of that conversation is continuously going back and saying, ‘Have you notified these people? Have you considered these next steps?’. It’s when we’re looking at really tightening our communications with our external partners, this is where this can be really beneficial because there’s less delay in that communication if they’re referring to the Mat Vat tool.

This view was supported by a Community Team Leader in Site 1 who reported that her team “are finding the MatVAT tool very useful – it’s a really good guide for what support they can put together for the women”. (Meeting notes, March 2022) and also a member of 29 the steering group who saw the potential for the checklist to support newly qualified midwives, or those less familiar with working in Community.

In contrast, the group of caseloading Community Midwives we spoke to in Site 1 felt that the tool didn’t offer as much added value to them as it might to those working in a traditional team:

CMW 2: We’re very privileged working in caseloading because, you know, if we pick up somebody who falls into category 2, we’re going to be seeing them again right through the pregnancy, so we can (…) keep an eye on them. You know, we might offer them another appointment, you know, or we might do an unexpected, you know telephone call or would… CMW1: I mean I have to say that I personally, and I’m sorry to say this really because I don’t want to be negative, but I think that the way that we work already, if I’m honest doesn’t make this format really very helpful, because I think that we’re already doing it. But that’s because we’re very privileged at working the way that we do, and I think that this would be incredibly helpful if I were doing a booking clinic, say, booking four people in one day and doing that three days a week. I think that could become my lifeline.

This raises the question of whether MatVAT is in effect compensating for the shortcomings of traditional community clinics over continuity of carer models. Caseloading midwives would also have less need to communicate between each other than those sharing information about one woman between different midwives for each appointment.

Key findings

- MatVAT can act as a prompt for midwives of possible referrals in response to Level 2 or 3.

- MatVAT may have less value for caseloading midwives than for those working in traditional clinics.

Recommendations

- Training in MatVAT could support newly qualified midwives’ confidence in working with safeguarding.

- Future work could focus on providing MatVAT for those working in traditional clinics to support communication between many health professionals working with one woman.

Intended Impact 4

Midwives and managers can formally quantify the complexity of their caseloads.

Neither site had yet implemented MatVAT as a way to quantify complexity for individual teams, during the pilot period. However, there was enthusiasm for this. One Community team was considering adopting MatVAT to replace postcodes as a proxy for social deprivation in their bespoke spreadsheet. They were keen to use this to help ensure individual midwives had women at different levels within their caseload and were not overburdened by too many women with high needs.

Key finding

- There is potential for MatVAT to be valuable in quantifying the demands of team caseloads to ensure even distribution of caseloads and to compare acuity between teams.

Recommendation

- Promote the role of MatVAT in monitoring acuity during future role outs.

7.3 How much was MatVAT used?

Key figures

Data was taken from Badgernet for patients who booked with any team from Site 1 between April 2022 and June 2022 (inclusive)15. Site 2 was excluded from this because they had moved away from using MatVAT during booking appointments in favour of internal triage.

Assessment details are from the first appointment in pregnancy. There were 2112 records (booking appointments) in total, of which 69 (3.3% of all records) had a MatVAT score recorded. This was expected as only two teams were implementing the MatVAT.

We wanted to know specifically about the use of MatVAT by those working in the two participating teams, which here we call ‘Traditional’ and ‘Caseloading’.

To do this, we conducted a sub-group analysis of those booking appointments carried out by a midwife from these two participating teams. However, as there have been very frequent moves between teams, we counted within these cohorts all bookings made by midwives who had ever booked for the two participating teams (Traditional and Caseloading), even when the current booking may not have been under that team16.

105 booking appointments were done during the period by midwives who had ever booked for ‘Traditional’ or ‘Caseloading’. Of these, 46 (44%) included a MatVAT score.

Which midwives used MatVAT?

There were 184 midwives undertaking bookings across the whole maternity service in the initial dataset. Nine midwives were included in the sub-group analysis and had ever taken a booking appointment as part of either of the participating teams.

Fifteen (8.2% of all midwives) used the MatVat tool at least once, which implies that some midwives used the tool outside of the pilot. The number of uses amongst all midwives ranged from 1 to 17 times during the two months.

| Team | Number (%) of MatVat scores recorded |

| Caseloading | 27 (39.13) |

| Traditional | 21 (30.43) |

| Other teams | 21 (30.43) |

The midwives who used the tool at least once did so in a high percentage of their total bookings (mean = 59.3%). However, some of these midwives did not have many bookings during that period. After they had used the MatVat tool for the first time, midwives went on to use it in an average of 51.0% of their subsequent bookings – showing that they continued to use it after the first time.

*Tradional1 / After first use = 0.0017

Together, these results show that all midwives who had been trained in MatVAT (as part of the two participating teams) used MatVAT at least once. Once MatVAT had been used once, amongst all midwives, the uptake was moderately good (midwives went on to use it in an average of 51% of their bookings).

Which women received a MatVAT score?

Those women with a score were assessed at the following levels:

| MatVAT level | N (%) |

| 1 | 54 (78.26) |

| 2 | 10 (14.49) |

| 3 | 3 (4.35) |

| 4 | 2 (2.90) |

We compared the women who did and did not have a MatVat score recorded to try and see whether the tool was only being used in particular populations18.

*p-value for difference19

The results suggest that deprivation score and ethnicity were similar across the level of need categories. However, there were significant differences in terms of age and gestation at booking.

Those that were categorised as 2 or higher tended to be younger and have later gestation at booking than those that were categorised as 1. In particular, those categorised as 3 or 4 booked 6 weeks later on average than those who were categorised as 1 or 2.

Safeguarding referrals

Only two service users were referred to a safeguarding midwife. One scored as 3 on the MatVat and the other scored as 4. The latter individual was also referred to the safeguarding lead. There were no other referrals to the safeguarding lead.

7.4 Factors affecting its use

The routine data shows that the use of MatVAT was variable between different midwives. There are many possible reasons for this and the final section of the report outlines some of the barriers to use that arose in the data collected.

Staffing and workplace demands

Some midwives perceived MatVAT as burdensome but this was in no small part because of the wider context within which it was operating. One community midwife described the impact of what she called a culture of ‘excessive documentation’ within the maternity services, which MatVAT played into:

She sees the main problem is that it’s yet another thing added to the documentation. At the moment they’re working in a culture with ‘excessive documentation’ that she feels doesn’t appear to be improving women’s experience or their outcomes, so she thinks it’s not surprising that MatVAT gets forgotten. She doesn’t think this is the case with MatVAT – she thinks it’s a useful tool – but it’s not surprising that it’s not being used in that broader context.

The pressures of time, particularly in traditional clinics, were also likely to make it difficult for midwives to engage with the tool, beyond what they would routinely currently do. These pressures were clear due to the difficulty for community midwives engaging with the project at all. Whilst MatVAT did not require any additional questions, initial reactions from those who had not received the training were that it was potentially time consuming. The dense layout appeared to be off-putting:

At first, I think there was a bit of pushback because it’s like, ‘Oh, this is really long.’ But I think they are really seeing the value of it now about, ‘Oh, what do we do with this? And what do we do with that?’ (Safeguarding Midwife, Steering Group). ‘Initial impression just looking at it, it’s very wordy and if you’re not overly familiar with it or have looked at it to make an assessment on something, that’s quite a lot to get through, but I suppose the more you use it…’

The small number of community midwives we spoke to who had used it did not raise this as a key problem:

(Community Midwife) said that the MatVAT does not take too much extra time to use. They use it at booking and refer as usual. Some of the referral pathways in the care planning document are good.

The high turnover of community midwives during the study period also had an impact, as midwives who were trained in MatVAT were then deployed to other teams, or left their posts.

Key findings

- Documentation is an unwelcome demand within services. MatVAT can be perceived as adding to that burden.

- Implementation is challenging within the current maternity crisis.

- Those who had received training in MatVAT and had used it were more positive about its use than others.

Recommendation

- Ensure clear communication with Trusts and frontline staff about the practicalities of implementing MatVAT, including widespread training.

Integration with IT systems

IT systems are universal and used to record information and decisions, and to prompt midwives to ask particular questions or do certain tasks:

We’re using electronic drug rounds to flag for allergies, for alerts, for safeguarding, then my question is, why wouldn’t we also use it for this sort of vulnerability as well, to guide people?

It was clear from what we heard that integration with the IT system was key to the future success of MatVAT. The pilot was necessarily set up without full integration with either Badgernet or Serna. Instead at one site the team repurposed a pre-existing log for Level 1-4 to record MatVAT. At the second site, the level was added manually into the narrative care plan. From the start, concerns were raised that these methods might be significant barriers to MatVAT’s use because they asked midwives to record items beyond their current default:

If it’s not been put on Badgernet, then it’s not being used.

CMW1: Can I ask you, did you do a MatVAT score this morning? CMW 2: No, I didn’t – say I was just gonna say so… I am aware of this, but I wouldn’t know whereabouts it is on Badgernet to do it.

think the only way it’s going to work for all midwives is if we build it into whatever computer system we use, because I have to agree with (steering group member), midwives don’t have the time to read all that (the written MatVAT page), but the information is necessary, but midwives don’t have the time. And so, if you just give it to them as another added piece of paper, rather than integrated into whatever they’re already using, I think you are going to get a pushback because I think midwives at the moment are already saturated and Covid hasn’t helped their mood.

One steering group member suggested taking the integration further, building a system that would automatically generate a MatVAT score in response to information in the IT system:

Because we ask about neglect, we ask about education and employment, we ask about the Whooley questions about the mental health, we ask about emotional wellbeing and we ask about the social development. We ask if English is their first language. So, that’s why I feel, as long as they’re normally asked, you just develop it to pull it through. So by the time the midwife gets to that tool, actually this scoring is already done.

Two Community Midwives were interested in the potential for MatVAT to use tick boxes to generate a score:

I also think that it would be much more helpful if it was more bullet points, because this (points to the main MatVAT page) – we don’t have time. There is not time, and even more so for those doing – where it would really be useful – in a booking clinic, you don’t have time to read it all through. But sort of a tick box method where you just see how many ticks you’ve picked up at a booking as you’re going along and then it will score. I think that could be really helpful.

If I was asking the questions, perhaps at the end of the assessment a level could come up, maybe, I don’t know. Yeah, it would flag up, you know.

Others wanted the computer system to use the MatVAT score to automatically generate a referral:

(Community Midwife) said that if the score ‘means something’ it would make it easier to embed into practice. She said that the table (care planning guide) was 37 useful to make sure you haven’t missed something. It would be good if the score triggered something internally (i.e. referral to the Psycho-Social Meeting).

Midwives desired this kind of tick box approach as they felt it was time-saving under intense workplace pressure, but also more in keeping with other tools they were using that aimed to introduce objectivity to complex situations. One midwife suggested that describing it as a ‘tool’ implied that it was electronic and automated.

Using MatVAT as intended required a level of comfort with ambiguity, complexity and intuition in an environment where some midwives wanted certainty and a perception of ‘objectivity’.

Key findings

- MatVAT requires full integration with IT systems.

- MatVAT should be positioned in a prominent place on the system and require as little as possible in additional data input.

- There is an appetite for automating some elements of MatVAT.

- Using MatVAT requires a level of comfort with complexity and ambiguity that may be at odds with conventional ways of working in the NHS.

Recommendations

- Some automation of the tool would be valuable – for example for a system to automatically aggregate social information into one field along with the MatVAT score to avoid midwives duplicating information to record the reasons for their score.

- If MatVAT continues to be a paper document, LEAP could consider referring to it as something other than a ‘tool’ as this implies an automatic, electronic process.

- LEAP should work with IT system developers to ensure the integration of MatVAT in the most commonly used NHS systems (e.g. Badgernet, Serner, EPIC).

Format and layout

Four tier structure

Familiar RAG colours

Quick tool a useful reminder

“Very wordy”

You almost don’t need to know off the top of your head every category, but for me, if I see red, I see red.

Initial impression just looking at it, it’s very wordy and if you’re not overly familiar with it or have looked at it to make an assessment on something, that’s quite a lot to get through.

The quick tool is very good.

Recommendations

- Consider ways to reduce the amount of text on the main page or simplify the layout.

- Continue the use of RAG colours and the four tier structure.

Training

The LEAP Health Team trained most midwives in Autumn 2021 from the four participating teams through repeated visits to the sites, catch-up one-to-one sessions and online training. The training was positively received with participants describing the tool as ‘excellent’ and ‘overdue’.

Participants appreciated the resources, the knowledge of the trainers and the use of a case study to apply MatVAT to real life. Participants brought up the challenges of syncing MatVAT with Badgernet. They questioned the impact of a potential lack of engagement or understanding from others and the potential for MatVAT to duplicate workloads.

The delays between the training and some midwives using the tool, meant that refresher training was requested by Site 1 in February 2022.

The more positive responses to the tool from those who had been trained as compared to those who had not, suggested that training was useful and necessary to implementation of the tool.

Key findings

- Training was well received.

- There appeared to be some misunderstandings of the intended use of the tool amongst those who had not been trained and this showed the importance of training to its success.

Recommendations

- Develop sustainable, scalable training in the use of MatVAT as part of any future roll out.

- If a wider roll out goes ahead, consider implementing training into pre-registration or preceptorship courses, or in CPD/re-accreditation requirements to ensure widespread familiarity.

Fidelity and consistency

Some members of the steering group who came from outside of the participating Trusts suggested that amendments might need to be made for MatVAT to work in their area. This introduced questions around fidelity to the original model and what the limits might be for changes to suit local contexts.

Recommendation

- Consider the implications of local contexts and set parameters or guidance in adjustments to the tool to suit local need when rolling out.

8.0 Conclusion and next steps

This was a challenging project that highlighted the difficulties of implementing any kind of change in a crisis. The low engagement with the project is likely to have been due to the workplace context and not necessarily because people disliked the tool. However, the response to MatVAT was varied.

The small sample size makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions, but LEAP may find some of the tentative patterns in the data helpful.

In general, those with a more positive reception were amongst:

- More senior staff

- Those with specialist safeguarding roles

- Those trained in and some familiarity with MatVAT

The small number of community midwives we spoke to were more hesitant about the value of the tool, but in many cases they were seeing it for the first time and drawing on first impressions rather than lived experience of using it in practice.

Safeguarding is a complex area of midwives’ work, full of fuzzy thresholds and inevitably subjective assessments. In addition, any assessment of social vulnerability is open to the influence of stigma, judgement and personal prejudices. There appeared to be a tension between this type of work and the requirement for rapid, efficient, ‘objective’, tick-box systems to manage the constraints of a service in crisis.

MatVAT attempts to bridge this gap by introducing structure and consistency to the complex landscape of safeguarding. It does still, however, require a high level of comfort with complexity, fluidity, subjectivity and intuition. This can feel at odds with the need for clarity, structure, objectivity and automation – something that increases with the pressures on time and staffing.

Whilst this evaluation was also victim to these challenges, we have been able to identify some of the ways in which MatVAT worked as intended and others in which it didn’t. We are not able to draw firm conclusions on the validity of MatVAT, nor on an appetite for a wider roll out, but the findings show that MatVAT provided a number of benefits over conventional practice.

The recommendations have focussed on the implications for future scale up and are summarised here:

Liaison with partners and collaborators

- Liaise with Local Authority Safeguarding Boards in the future development of MatVAT to ensure an independent role for MatVAT away from LA thresholds.

- Ensure that the relevant Local Authority agencies, Health Visitors, GPs and all midwifery teams are familiar with MatVAT.

Implementation

- Consider other potential uses for MatVAT in future marketing and roll out.

- Any Trusts that adopt MatVAT should ensure widespread roll out throughout their services, to provide continuity of use and to embed it within internal referral processes.

- Future work could focus on providing MatVAT for those working in traditional clinics to support communication between many health professionals working with one woman.

Training

- Ensure clear communication with Trusts and frontline staff about the practicalities of implementing MatVAT, including widespread training.

- Develop sustainable, scalable training in the use of MatVAT as part of any future roll out.

- Training in MatVAT could support newly qualified midwives’ confidence in working with safeguarding.

- If a nationwide roll out goes ahead, consider implementing training into pre-registration or preceptorship courses, or in CPD/re-accreditation requirements to ensure widespread familiarity.

Integration with IT systems

- Some automation of the tool would be valuable – for example for a system to automatically aggregate social information into one field along with the MatVAT score to avoid midwives duplicating information to record the reasons for their score.

- LEAP should work with IT system developers to ensure the integration of MatVAT in the most commonly used NHS systems (e.g. Badgernet, Serner, EPIC).

Format and layout

- If MatVAT continues to be a paper document, LEAP could consider referring to it as something other than a ‘tool’.

- Consider ways to reduce the amount of text on the main page or simplify the layout.

- Continue the use of RAG colours and the four tier structure.

9.0 Acknowledgements

Dr Danielle Bodicoat, Simplified Data (www.simplifieddata.co.uk) provided the quantitative analysis and statistical support.

Thanks to:

Octavia Wiseman, LEAP

Claire Spencer, LEAP

Carla Stanke, LEAP

The project steering group were:

Dr Tracey Cooper, NHSE

Sophie Russell, University Hospitals Lewisham

Dr Sue Mann, Public Health England

Kirsty Kitchen, Birth Companions

Sarah Green, Chelsea & Westminster NHS FT

Nina Khazaezadeh, NHSE

Tracey MacCormack, King’s College Hospital

Dr Alison Little, Public Health Agency, Northern Ireland

Virginia Hewitt, Public Health Wales

Heather Innes, NHS Dumfries & Galloway

Professor Jane Sandall, King’s College London/NHSE

Sarah Scott, Guy’s and St Thomas’ MVP

Agnes Agyepong, Guy’s and St Thomas’ MVP and Best Beginnings

Clare Church, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS FT

Angela Ugen, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS FT

Gavin Moorghen, Social Work England

Mercy Ughwujabo, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS FT

Miriam Donaghy, Mums’ Aid

Gina Brockwell, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS FT

Shereen Cameron, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS FT

10.0 Appendix 1: MatVAT