LEAP’s Community Activity and Nutrition service – learning journey

Learning journey, August 2024

LEAP’s Community Activity and Nutrition (CAN) service – full report

1.0 Purpose of this document

Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP) developed this Learning Journey to capture the story of LEAP’s Community Activity and Nutrition (CAN) service over its lifetime: from its inception to the end of its journey as part of the LEAP programme.

A key focus of a Learning Journey is on implementation: how the service was delivered and the different resources required to do this. Learning Journeys are service summaries, not service evaluations, and are part of a wider suite of LEAP research and learning projects designed to capture insights into our progress towards giving children in the LEAP area a better start in life.

Information contained within this report was taken from national policy and evidence as well as from a variety of internal LEAP documents including:

- service plans;

- theories of change;

- monitoring, evaluation and learning frameworks;

- quarterly narrative reports and service data reports;

- workforce and client feedback;

- minutes from service reviews and team meetings.

Learning Journeys were co-written between service leads and members of the LEAP team. The Key Messages were based on high-level reflections drawn from the available data and insights gleaned over years of service delivery.

We will share our Learning Journeys with key stakeholders including the National Lottery Community Fund; local early years commissioners and public health colleagues; service delivery partners; families; and via national public health networks as appropriate.

Our hope is that the learning from the LEAP programme can inform future commissioning and programming decisions and contribute to the wider evidence base about health improvement interventions in the earliest years.

2.0 Background

2.1 What is LEAP?

LEAP is one of five local partnerships which make up ‘A Better Start’ – a national ten-year (2015-2025) test and learn programme funded by the National Lottery Community Fund that aims to improve the life chances of babies, very young children, and families. LEAP is a collective impact initiative, which means that our services and activities link together and work towards shared goals to improve outcomes for very young children.

2.2 Why is addressing maternal weight in pregnancy important?

Maternal nutrition is critical for the health and well-being of women and their infants. Supporting pregnant women/birthing people with a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 25 or higher is important. BMI is a measure of whether a person has a healthy weight for their height.

Starting pregnancy with excess weight or gaining excessive gestational weight has both short- and long-term health problems for both the woman and the developing fetus, with subsequent wider public health implications.

During pregnancy the short-term consequences for women include a higher risk of developing pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, thromboembolism, and having an emergency caesarean delivery. There is also an increased risk of infection and breastfeeding difficulties.1

Complications such as gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia are associated with long-term morbidities post-partum for women, including type 2 diabetes.2 Additionally, excessive gestational weight gain is common during pregnancy and this weight gain is linked to being overweight and obese in later life.3 4

For the developing baby the short-time complications include congenital malformations, macrosomia and stillbirth. In the long-term, infant birth weight is linked to type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in adulthood.5

Maternal obesity has been cited as a major determinant of offspring health during childhood and later adult life, through changes in epigenetic processes. A systematic review, which included 79 studies from international settings, identified a 264% increase in the odds of developing childhood obesity when mothers are obese before conception.6

2.3 Causes of pregnant women starting pregnancy with a BMI ≥ 25

It is well established that the causes of women starting pregnancy with excessive weight are complex and multi-factorial. Of particular relevance for LEAP include the impacts of living in an obesogenic society and the impacts of living in a deprived area.

The term ‘obesogenic environment’ was coined in the 1990s and can be defined as a context of unhealthy sociocultural, physical, economic and political environments that impact upon the key drivers of obesity: physical activity and food intake.7 Post-industrial society has witnessed the rise of a ‘toxic food’ culture, with the availability of high-calorie processed food making excessive weight gain easy.8

Changes in food production and processing; the role of the media in advertising; the increasing popularity of fast-food restaurants; and reductions in physical activity, due to changing work environments and modes of transportation, have undoubtedly fuelled this transition.9

Alongside living in an obesogenic society, it is also important to consider the demands placed on women in everyday life. Women have become increasingly busier. Having to juggle the demands of work and domestic life has spilled over into family, exercise and leisure times in complicated ways.10

There is a deprivation gradient with maternal weight status. Women have increased odds of their BMI being above or below the recommended range as the level of deprivation increases. Furthermore, alongside increasing levels of deprivation and poverty in the UK, food insecurity is also increasing.

Women are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity due to working in low-income or part-time jobs in addition to acting as the main family carers. Women report restricting their own food intake in favour of their children and other household members.11

Food insecurity is linked with a nutritionally poor diet and the consumption of energy-dense processed food which further increases the risk of gaining excess weight. It has been argued that continuing increases in food insecurity, and the implications of this on maternal nutritional health and wellbeing, and the potential impact on fetal development, are severe.11

2.4 The implications of multiple inequalities through an intersectionality lens

It is important to consider the implications of multiple inequalities through an intersectionality lens.

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework used in public health which addresses the ways in which individuals’ experiences are shaped based on their intersecting social identities e.g., ethnicity, gender, economic position, age, etc.12 Thus, different inequalities such as deprivation, food insecurity, ethnicity and obesity, in addition to stigma and discrimination, collide and have a cumulative impact on pregnancy health.11

Disparities in relation to ethnicity in maternal mortality rates, stillbirth, preterm delivery and perinatal mortality are well established. A UK-national, population-based cohort study found that women of Black ethnicity remained at significant increased risk of maternal death compared with women of white ethnicity. Among women of White ethnicity, risk of mortality increased as deprivation increased, but women of Black ethnicity had greater risk irrespective of deprivation.13

Additionally, women of Black and South Asian ethnicity living in the highest deprivation quintile were at highest rate for stillbirth, preterm delivery and fetal growth restriction.14 The concept of intersectionality is important for the CAN service, which is delivered to pregnant women from diverse ethnic groups who live in areas of greater deprivation.

2.5 Understanding the level of need

The rise in people living with excess weight has been described as a global pandemic.

Worldwide adult obesity has more than doubled since 1990, and adolescent obesity has quadrupled. In 2022, 43% of adults aged 18 years and over were overweight and 16% were living with obesity. 37 million children under the age of 5 were overweight and over 390 million children and adolescents, aged 5–19 years, were overweight, including 160 million who were living with obesity.15

Within the UK, there has also been an increase in adults who are either overweight or obese and an increase in childhood obesity. In 2021, 38% of the adult population were overweight and 26% were obese.

Between 2019/20 and 2020/21, the prevalence of obesity in reception-aged children increased from 13% to 20% in the most deprived areas; in the least deprived areas this increased from 7% to 9%.

Similarly, the prevalence of obesity in children in Year 6 increased from 22% to 32% in the most deprived areas, and from 13% to 16% in the least deprived areas. The increase in prevalence was disproportionately higher for children in the most deprived areas.16

Currently, half of women in the UK have a BMI of 25 or higher when they start their pregnancy. In England, the overweight prevalence in pregnant women is 28% and obese prevalence is 21%.11

In England there is variation between ethnic groups when looking at BMI status in maternity booking data (data collected at a woman’s first midwife appointment). In 2017 two-thirds (66.6%) of Black women were overweight or obese. Women of Asian (51.8%), mixed (51.2%) and White (48.6%) ethnicities also had high rates of being overweight and obese.17

The data for Lambeth demonstrates that maternal weight is also a problem for the LEAP population. In 2017/2018, 780 women living in the LEAP geographic area booked with Guy’s and St Thomas’ (GSTT) and King’s College Hospital’s (KCH) maternity departments. Of these women, 23% had a BMI between 25 to 29.9 (overweight) and 18% had a BMI ≥30 (obese).18

Within Lambeth, children are more likely to be overweight or obese at school entry if they live in areas of higher deprivation. The prevalence of overweight and obese children in reception in Lambeth in 2022 was 23%. In the LEAP area, 29% of children in reception were overweight or obese.19

2.6 Recommendations and evidence-based approaches

The last NICE guidelines on weight management in pregnancy and management of obesity during pregnancy were published in 2010. The guidelines focused on beginning pregnancy at a healthy BMI; providing information and advice on a balanced healthy diet and physical activity during pregnancy; and a return to a healthy BMI in the postnatal period.20

They also advised that women within the obese category should be educated about the risks associated with maternal obesity, both to their own health and that of the developing fetus. The same recommendations were also made in the 2018 Royal College Obstetricians Gynaecologists Green Top guideline.21

A World Health Organization (WHO) report stated that interventions that improve maternal nutritional status are both an effective and sustainable means of achieving positive impacts on health and reducing inequalities in health across the next generations.22

In relation to ethnic disparities, a recent study highlighted the challenges that African migrant women face in balancing their cultural heritage with the UK food environment and dietary recommendations. This included potential implications on their health and pregnancy outcomes and argued the importance of addressing these challenges through culturally sensitive approaches and tailored interventions.23

The UPBEAT study was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) carried out at antenatal clinics in eight hospitals in multi-ethnic, inner-city locations in the UK. It aimed to investigate whether a complex intervention addressing diet and physical activity could reduce the incidence of gestational diabetes and large-for-gestational-age infants. The UPBEAT model involved different components:

- Prioritising pregnant women with a BMI ≥ 30 who lived in deprived areas

- Swapping foods to lower GI options and increasing physical activity

- Running 8 sessions delivered by a health trainer24

Whilst the intervention showed no effect on preventing gestational diabetes, there was a significant reduction in gestational weight gain. There were also improvements in diet and physical activity levels.

From a long-term perspective, results from a secondary analysis of UPBEAT data suggested that a low-GI diet may have had an effect at epigenetic level, therefore, having a life course impact beyond pregnancy.25 A follow up study at three years found lower offspring pulse rate and sustained improvement in maternal diet.26

3.0 LEAP’s Community Activity and Nutrition (CAN) Service

The LEAP CAN service was based on the intervention used in the UPBEAT randomised control trial, with some adaptations to ensure the service would be acceptable to the local LEAP population. CAN was commissioned by LEAP in 2015 and recruitment to the service commenced in January 2016. The service delivery process is described below.

3.1 Focus groups/ initial adaptations

From Spring 2015 until January 2016 the LEAP CAN team arranged focus groups and attended community events with local LEAP women and families. At these groups, the proposed CAN service was presented. The overwhelming response was positive, and it was felt that CAN would be beneficial for the LEAP area.

Following these consultations the main adaptation made was to expand the service to women starting pregnancy with a BMI ≥ 25, rather than ≥30 as in the UPBEAT model. This decision was based on feedback in support of making the service available to more women.

Another important adaptation from UPBEAT was to offer the programme to non-English-speaking women using translators. This was an important change as there is evidence that limited English proficiency is a key factor associated with poorer maternal and neonatal outcomes.27

3.2 Team structure/ responsibilities

The LEAP CAN delivery team consisted of one full-time, band 7, project midwife (this was one Whole-Time-Equivalent job shared between two band 7 midwives) and three Band 4 health improvement facilitators (HIFs). All were based within/employed by Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (GSTT). Line management for the team was provided by the Consultant Midwife at GSTT.

The project midwife was responsible for the operational aspects of the programme which included recruitment; undertaking midwife appointments; providing quarterly reports and data for the commissioners; and supporting the HIFs with their case load. The midwife appointments included overseeing the completion of questionnaires, such as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), a validated tool that health-related physical activity in populations, and service feedback forms.

The HIFs were responsible for delivering the intervention. In the UPBEAT RCT, the intervention was delivered by health trainers. The health-trainer model was developed as a lay role for improving health among deprived communities and thereby reducing health inequalities.28 Within this model, the emphasis was on lay individuals/practitioners being trained to improve the health of members of their own communities, by signposting clients towards services.

In the UPBEAT study, the health trainers received study-specific training in all aspects of the intervention. Health trainers were also employed/trained for the CAN service – however, their title was changed to health improvement facilitators during the programme, in line with changes to the other health trainers working within GSTT.

3.3 Recruitment process

The CAN midwife was responsible for the recruitment process. A literature review identified the challenges that midwives encounter when supporting women with their weight. These included midwives’ level of expertise, perceptions of their ability to influence and an awareness of their own weight.29 For effective recruitment, it is important that the professionals involved are confident in discussing weight with pregnant women. Eligibility criteria for being offered the CAN service were:

- Living in the LEAP geographic area

- Being pregnant and having the baby at GSTT or King’s College Hospital (KCH)

- Having a BMI of 25 or higher at the first booking appointment with midwife

The maternity IT systems at GSTT and KCH allowed the CAN midwife to identify all pregnant women who met the eligibility criteria. Woman who had a documented eating disorder on their booking history were not contacted.

The recruitment process involved three steps:

- Invitation letter and leaflet sent (see appendices A and B) to the woman in the post. From this letter, women could sign up to the service directly. Invitation letters were not sent out until after a woman had her first trimester scan to ensure that the pregnancy was still viable.

- If a woman did not sign up to the service after receiving the recruitment letter, up to three phone calls and/or text messages were sent. The telephone call was an important part of the recruitment process, as although women may have received the invitation letter in the post, a thorough one-to-one conversation with the midwife addressed any queries/concerns. The text message included a link to the service description on the LEAP website (see appendix C).

- For women who agreed to participate, the first appointment with the CAN midwife was scheduled for a time that suited the woman.

3.4 Service delivery process

1st midwifery appointment

The first appointment, at up to 20 weeks gestation, provides an introduction to the service by the midwife. The topics discussed include the health benefits of the service, explanation of Glycaemic Index (GI) and the impact of foods on sugar levels and energy. A health history is taken, and baseline physical activity is measured using the IPAQ.

A CAN Participant Manual and pedometer watch are given if this is a face-to-face visit; otherwise, these items are sent by post if the first appointment is via telephone. The first session with a HIF is also scheduled.

Eight sessions with Health Improvement Facilitator

The next part of the service consists of eight one-to-one sessions delivered by HIFs.

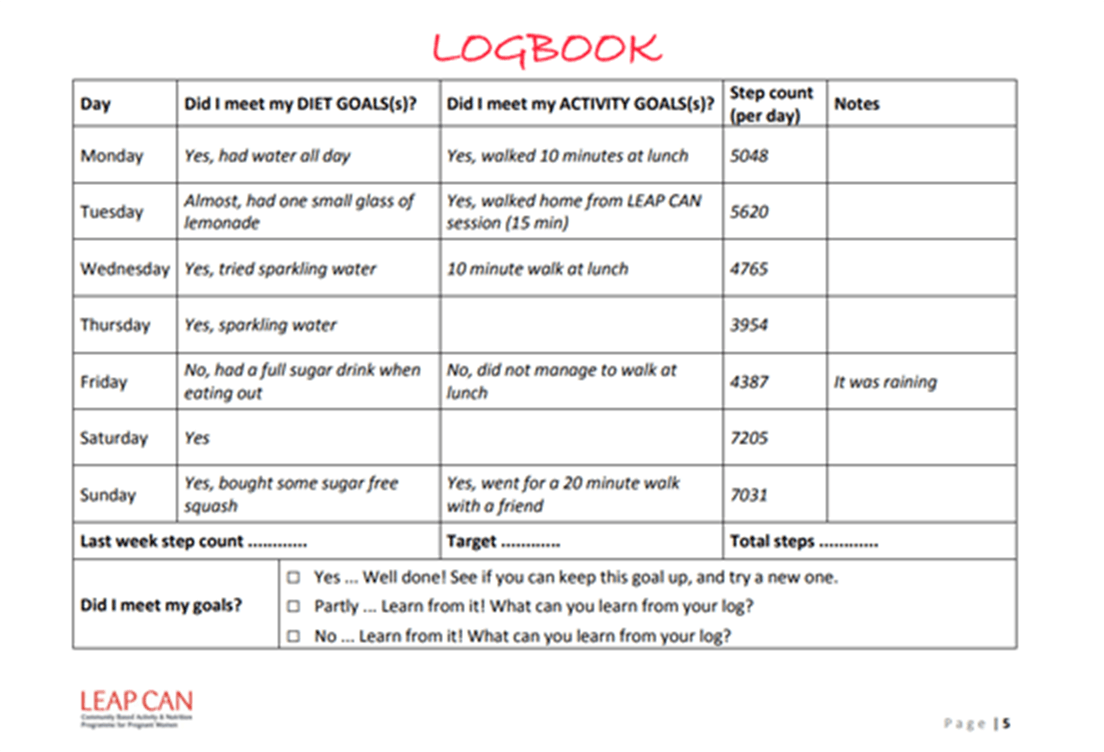

Each session consists of setting SMART goals (i.e., specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-specific) to support women to make changes to their diet and physical activity levels. Women document the set SMART goals and their weekly progress in a logbook that is given at the beginning of the programme.

At each session the previous week’s goals are reviewed, and HIFs encourage women to build on changes made week by week. As a behaviour change intervention, the sessions aim to improve glucose tolerance through dietary and physical activity changes.

For the dietary component, a healthy pattern of eating was promoted with an emphasis not to restrict food intake (dieting during pregnancy is not recommended as it may harm the health of the unborn child).

Importantly, recommendations were tailored to women’s cultural foods, with an emphasis of exchanging carbohydrate-rich foods with a medium-to-high glycaemic index for those with a lower glycaemic index along with restricting dietary intake of saturated fat.

Sensitivity was given to both women’s previous relationship with food in addition to recognising the difficulties they may experience in pregnancy, e.g. nausea or food aversions.

For the physical activity component, the main emphasis was on incremental increases in walking, monitored through the use of a pedometer watch. Depending on the woman’s prior exercise activity, other forms of activity were also recommended, especially those already on offer within the LEAP area, e.g., pregnancy yoga, Zumba or walking groups.

Content of sessions with HIFs (each session lasts about an hour)

Session 1: Sugary drinks and added sugar to food

The first session enables the pregnant woman to meet her HIF so they can begin establishing a relationship.

The HIF asks questions about the woman’s life (e.g., her family and living situation, current physical activity levels, dietary preferences, etc.) and uses this information to ensure that ongoing support is tailored to her specific needs. The overall aim of CAN – for a woman to make small changes around physical activity and diet – is reiterated.

This session also introduces the idea of goal setting and using the logbook to record progress. Each week, between sessions, a woman is asked to work on her goals and the target she has set for herself.

In relation to nutrition, women are encouraged to think about dietary swaps they could make. These swaps are very individual and dependant upon current eating habits. In relation to physical activity, women are encouraged to increase the amount of physical activity they do. This will be about making small but important changes such as increasing the amount of walking and reducing the amount of time sitting down. This will involve setting step targets and using a pedometer watch.

The first swap involves swapping soft drinks for sugar-free alternatives, including water, herbal or fruit teas and semi-skimmed or skimmed milk. The HIF reviews food labels with the woman and discusses how to determine the sugar content of a drink. The dietary goal for this session is about swapping soft drinks for sugar-free alternatives, and the physical activity goal is to increase walking. Women are asked to record their daily step counts in their logbook.

Another swap this week involves cutting down on the sugar added to foods, e.g., using fruit to sweeten food (like porridge) instead of sugar.

Session 2: Carbohydrate and portion size

The swap this week involves swapping white or brown bread for multigrain or granary bread. This type of bread is the best choice for CAN clients because it does not affect blood sugar levels as much as other types of bread.

HIFs advise women who eat rice and potatoes on a regular basis to choose the types carefully because certain types of rice and potatoes can affect blood sugar levels more than others. Basmati rice, steamed or boiled sweet potato and yam are recommended. Teff injera and grilled plantain are also recommended carbohydrates.

HIFs emphasise the importance of correct portion size/low GI foods and a healthy balanced diet. They explain that eating the right amount of food regularly and not skipping meals may help reduce blood sugars rising quickly and spiking. In addition, this approach also helps to reduce excessive weight gain in pregnancy.

Session 3: Snacks and reading food labels

This swap involves swapping sugary snacks like chocolate, biscuits, puff puff, chin chin or achomo for healthier snacks like fresh fruit, unsalted nuts, low-fat yogurt or lentil crisps. Women are encouraged to be prepared for snack attacks and keep some fresh fruit and healthy snacks handy at all times. Sugary snacks like chocolate and biscuits should be an occasional treat.

CAN participants are supported to better understand the nutritional information on food labels, specifically the information about fat and ‘carbohydrates, of which sugars.’ HIFs support women to understand the thresholds for determining if a food has low, medium or high sugar/fat content and encourage women to consider the frequency with which they eat food with higher sugar/fat content.

Session 4: Breakfast choices

This swap involves swapping cereal containing added sugar with porridge (rolled oats or cornmeal), lower sugar cereals or no-added-sugar granola.

Session 5: Dairy and non- dairy sources of calcium

This swap involves swapping higher fat foods like full-fat cheese, whole milk, butter, ghee, coconut cream or palm oil with lower fat dairy products like reduced-fat hard cheese, skimmed or semi skimmed milk, olive oil, sunflower oil or low-fat yogurt.

Session 6: Fat/meat/protein rich foods

For women who eat meat, this swap involves choosing meat and meat products carefully to lower intake of unhealthy or saturated fats. Women are encouraged to choose leaner cuts of meat and trim fat and skin off meat and chicken, and to drain the fat off mincemeat before adding other ingredients when cooking.

Women are also encouraged to include pulses like beans, lentils, peas and chickpeas as an alternative to meat.

Session 7: Eating out and take away food

Women are encouraged to reduce their consumption of takeaways or fast foods . For women who do eat out, they are encouraged to try to apply the CAN suggestions (e.g., swapping high glycaemic index foods for lower glycaemic index foods, choosing foods with lower saturated fats) and make healthier choices where possible.

Session 8: Review and feedback

During the final session, the HIFs review all the SMART goals set in the previous seven sessions. This allows women to consolidate their learning and reflect on their achievements. Women are also encouraged to reflect on which aspects of the programme they had found easier and which they had found more difficult.

2nd midwifery appointment

The second midwifery appointment happens after a woman completes all 8 sessions with a HIF (around 28 weeks gestation). At this point, feedback about the service was obtained using LEAP’s Family Feedback Questionnaire and physical activity was measured using the IPAQ.

Women were also signposted/referred to other LEAP services as appropriate. Examples of LEAP services signposted/referred to included LEAP Breastfeeding Peer support service, Baby Steps (a perinatal education programme), Healthy Living Platform (for community food support) and PAIRS (a parent-infant mental health service). Referrals were also made to non-LEAP services such as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT).

3rd midwifery appointment

The third midwifery appointment occurred at 6 months postnatally. At this appointment physical activity was measured again using the IPAQ.

Further signposting/referrals to wider LEAP services occurred, in addition to any GP/IAPT referrals if mood change were disclosed. Additionally, participants were signposted to Introduction to Solids Workshops as their babies were now old enough to eat solid food.

3.5 Resources

All women taking part in the programme received a participant manual, pedometer watch and a logbook.

Participant manual

The participant manual is a comprehensive guide to participating in the CAN service. It includes an explanation about Glycaemic Index and how different foods can affect blood sugars, as well as examples of food swaps, healthy recipe suggestions and suggestions for physical activities in the local area.

The manual also includes general advice on foods to avoid and restrict during pregnancy, the benefits of breastfeeding, top tips for oral health in babies, top tips for introducing babies to solid food and general maternal wellbeing. Examples from the participant manual are in appendix D.

Logbook

A logbook was given to women to record their weekly SMART goals in relation to both dietary changes and increasing physical activity (see appendix E).

Pedometer watch

Each woman was given a basic pedometer watch to encourage walking and to support setting goals for increasing physical activity each week (see appendix F).

3.6 Venue settings

The service was initially offered in either local children’s centres or at a woman’s home. The benefit of offering the service in a children’s centre meant that women were introduced to other local services also delivered there.

Some women opted for home visits as this suited them better, especially if they required an evening visit. During the pandemic, the service was delivered via telephone. When restrictions associated with the pandemic were lifted, positive feedback was given about the telephone sessions, especially about how they fitted into women’s busy schedules. As a result, the service adopted a hybrid model of delivery with both face-to-face sessions in the children’s centres and telephone sessions.

3.7 Timing/groups

In the UPBEAT RCT, most sessions were delivered one to one as it was very difficult to form groups due to women’s busy schedules.

The CAN service was developed so that it could be undertaken either in groups or via one-to-one sessions. When it was initially rolled out in the LEAP area, groups as well as individual appointments were offered. However, the demand for individual appointments was high and group delivery was discontinued.

The timing of the appointments needed to be flexible. Women could request evening appointments and sometimes Saturday appointments.

3.8 Adaptations during the lifetime of the service

A number of adaptions were made over the lifetime of the service, to ensure the service remained relevant and inclusive for the LEAP population.

Eligibility criteria

As previously highlighted, during initial local consultations, the service’s eligibility criteria were changed from offering it to women with a BMI of ≥30 to ≥25 and also included non-English speaking women. These changes were implemented so that more LEAP pregnant women could benefit from the bespoke diet and physical activity support offered by the service.

Resources

The participant manual was regularly reviewed to ensure that the recipes represented the local LEAP community. For example, East African and South American recipes were included in the last edition after an increased take up of the offer from women from these communities.

Some resources were translated into Spanish. This was following a review of the data which demonstrated that Spanish was the main language spoken in the non-English speaking group of participants.

Service delivery

A weekly walking group, led by the HIFs, was introduced so that CAN participants could meet each other and exercise together in a social, casual way.

An email version of the service was developed following feedback that women declined participation in CAN because of lack of time. The email version consisted of weekly emails sent to women by the HIFs with the expectation that women would make diet and physical activity changes on their own, without personalised support, along with an offer of a 15-minute phone call with a HIF to answer any questions.

The rationale for trialling an email offer was that women could undertake the service in their own time, thus appealing to women who refused due to time constraints. However, after this element was introduced, women who cited time as a reason for refusal continued to decline the offer.

Women who had started the face-to-face service, but were thinking of leaving due to time, were switched over to the email version. However, only 9 women ever used the email version of the service.

Other innovations

In 2022 the HIFs were trained by HENRY30 to deliver workshops about introducing babies to solid food. The service aimed to help babies have the best possible start to their lifelong food journey. It did this by supporting parents to introduce solids in a way that established healthy eating habits and preferences.

CAN women were invited to these workshops, and they were also freely available for any parents/carers living in Lambeth. This service filled a local gap and complemented the CAN service.

LEAP developed a sister service of CAN called Pregnancy Information on Nutrition and Exercise (PINE). PINE was a service for pregnant women between 12 – 24 weeks gestation with a BMI of 18.5–24.9 who lived in Lambeth and booked to have their babies at one of the two LEAP-area NHS trusts (GSTT or KCH). Via one-off workshops, PINE aimed to provide light-touch support to increase women’s knowledge and awareness of nutritional needs and the importance of physical activity during pregnancy.

3.9 LEAP Theory of Change

LEAP developed a theory of change for CAN (Figure 1). The key desired outcomes were an improved diet and increased physical activity during pregnancy and beyond, including subsequent pregnancies, and babies being born with a healthy birth weight. LEAP aimed to achieve this with the following medium-term outcomes:

- CAN women have increased knowledge, confidence and motivation to adopt a healthy diet and lifestyle

- Health improvement facilitators feel confident and competent to deliver the sessions with CAN women

- Women from our priority population have increased knowledge, confidence and motivation to adopt a heathy diet and lifestyle

- Participants from other services hear and respond positively to the key CAN messages

- Families access Breastfeeding Peer Support and HLP

4.0 Outcomes, reach and feedback

Since the LEAP CAN service began service delivery in 2016, data has been collected on different elements of the service:

- Demographic data about service users

- Data about birth outcomes for service users

- IPAQ scores collected at three time points as described in section 3.4

- Feedback from service users about changes to their knowledge and confidence as a result of the service, collected upon completion of the service (Family Questionnaire form)

- Feedback from services users about their experience of CAN, collected upon completion of the service (Family Feedback form)

- Service user data about Starting Solids participants

Based on the data collected, it is possible to reflect on two medium term outcomes from the Theory of Change (ToC):

Medium term outcome 1: CAN women have increased knowledge, confidence and motivation to adopt a healthy diet and lifestyle

Family Questionnaires about CAN measure knowledge, confidence and motivation to eat more healthily and exercise more. They are completed at the 28-week appointment, which marks the end of service delivery. Overall, participants report high levels of knowledge, confidence and motivation:

Knowledge

- 93% report high or very high knowledge of recipes to cook at home

- 91% report high or very high knowledge of the types of exercise that fit well with their current lifestyle

- 46% report high or very high knowledge about where to find help or support with breastfeeding

- 89% report high or very high knowledge about where to find help and advice about diet

Confidence

- 83% report high or very high confidence in choosing healthy foods even if tired or busy

- 81% report high or very high confidence in choosing healthy foods even if family/friends are choosing unhealthy foods

- 68% report high or very high confidence in exercising regularly even if tired or busy

- 71% report high or very high confidence in meeting their exercise goals

- 88% report high or very high confidence in meeting their healthy eating goals

Motivation

- 88% report high or very high likelihood to breastfeed their baby

- 85% report high or very high likelihood to choose healthy snacks

- 94% report high or very high likelihood to cook healthy meals at home

- 90% report high or very high likelihood to exercise for 30 minutes at least three times per week

Medium term outcome 3: women from our priority population have increased knowledge, confidence and motivation to adopt a heathy diet and lifestyle

Using descriptive analysis, it is possible to understand more about the characteristics of CAN participants.

From 2016 – 2023, CAN supported 734 pregnant women. 70% lived in areas of deprivation in Lambeth (locally calculated IMD quintiles 1 and 2*) and 80% were from Black, Asian and Multiple Ethnic groups.

Weight categories

Using NICE definitions of overweight and obesity,31 participants were categorised into the following groups:

- Overweight: 51%

- Obesity class 1: 30%

- Obesity class 2: 12%

- Obesity class 3: 7%

Gestational diabetes

534 women were tested for gestational diabetes; of these 68 were diagnosed. Of those diagnosed, the ethnic distribution was as follows: 59% Black, 24% Other, 9% Asian and 7% White. More than 60% of those who were diagnosed were from IMD groups 1 and 2. The BMI categories for women diagnosed with gestational diabetes were: 43% overweight, 32% obesity class 1, 16% obesity class 2 and 9% obesity class 3.

Completion

Participants who attended 4 sessions with a HIF were considered to have completed the service. The maximum number of sessions is 8.

- 501 women (68%) attended 4+ sessions

- 331 women (45%) attended all 8 sessions

In the UPBEAT study, 83% of women attended 4 sessions or more and on average most women attended 7 sessions. 23

Other medium-term outcomes

Data was not collected on medium-term outcome 2 (‘Health improvement facilitators feel confident and competent to deliver the sessions with CAN women’) so we cannot report on this outcome.

Qualitative feedback from participants (summarised further down in this section) reflects very high levels of satisfaction with the service, with specific comments about practitioner knowledge and support provided. This indicates that the CAN team carried out their work with skill and confidence.

Data was not collected on medium-term outcome 4 (‘Participants from other services hear and respond positively to the key CAN messages’) so we cannot report on this outcome. Data was not collected on medium-term outcome 5 (‘Families access breastfeeding peer support and Healthy Living Platform’ {a community food service}) so we cannot report on this outcome.

Throughout the lifetime of the service, the CAN team developed strong links with several other LEAP services, including breastfeeding peer support, the Healthy Living Platform and Baby Steps. While data was not collected about onward referrals/signposting, the team prioritised providing integrated, holistic support for women as part of their routine practice.

Physical activity levels

Physical activity levels were measured three times using the IPAQ: at registration in the early 2nd trimester, at 28 weeks and again at 6 months postnatally. A total of 699 unique participants completed an IPAQ questionnaire for at least one time point, with 1,409 assessments completed overall. The breakdown below reflects participants (not unique individuals) who have assessments recorded at each of the three time points:

- 693 at registration

- 357 at 28 weeks

- 243 at 6 months post

Using descriptive analysis, it is possible to understand average changes in physical activity levels in CAN clients.

Activity levels

For those participants who had an IPAQ assessment, 45% of participants had low and 49% had medium activity levels at registration, which improved by 28 weeks (24% low and 69% medium activity). The proportion of people who had high activity levels increased by each assessment point; this figure nearly doubled between registration (5.7%) and 6 months (10.0%). This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Activity time

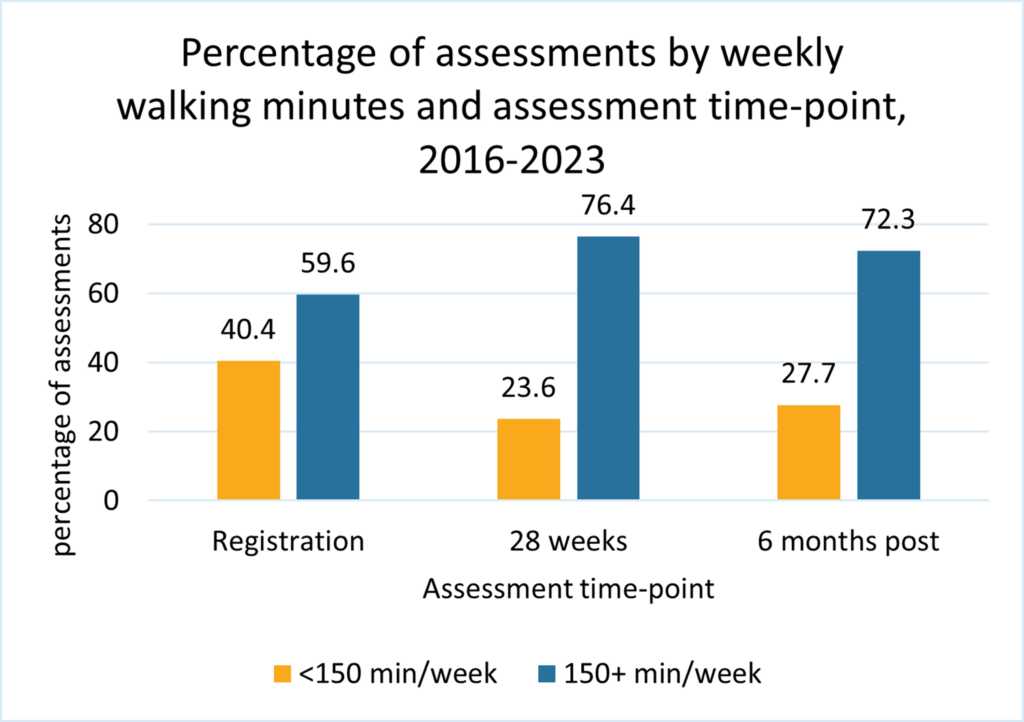

The proportion of participants, who walked more than 150 minutes per week, increased from 59.6% to 76.4% between registration and 28 weeks, and decreased slightly between 28 weeks and 6 months. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

The proportion of participants, who did more than 150 minutes per week of moderate or vigorous activity, increased from 9.4% to 13.3% between registration and 6 months postnatally. This is illustrated in Figure 4.

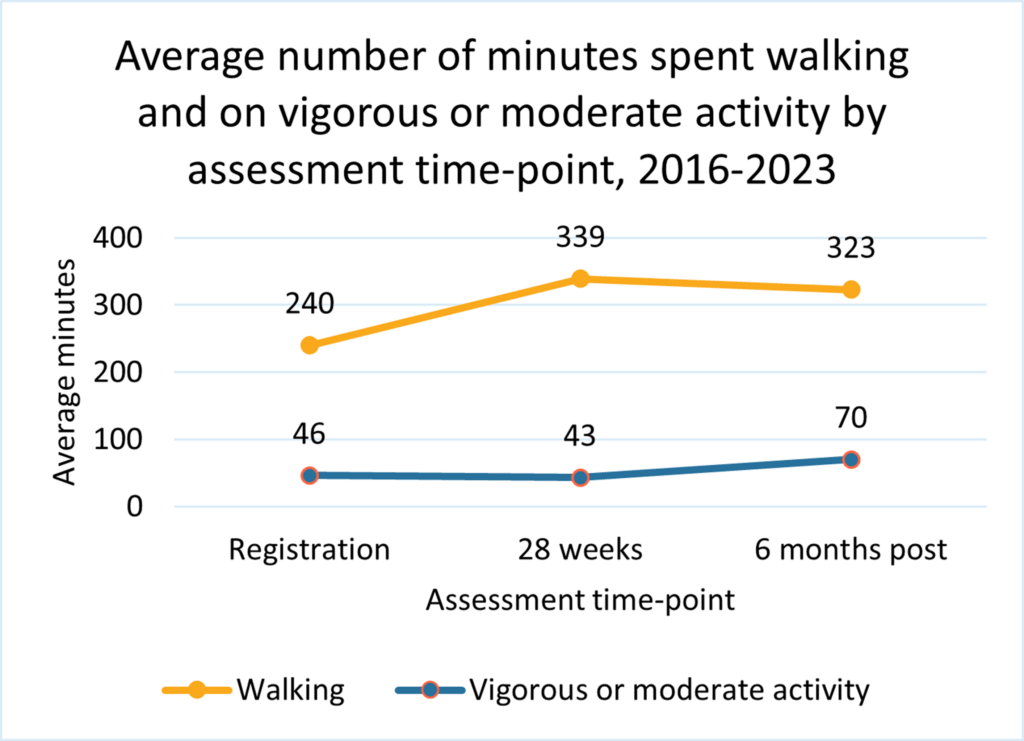

Average time spent walking increased from 240 to 323 minutes between registration and 6 months, which reflects an average increase of 35% overall. A slight decrease was seen between 28 weeks and 6 months. Moderate or vigorous activity minutes increased from 46 to 70 minutes between registration and 6 months, which reflects an average increase of 52%. This is illustrated in Figure 5.

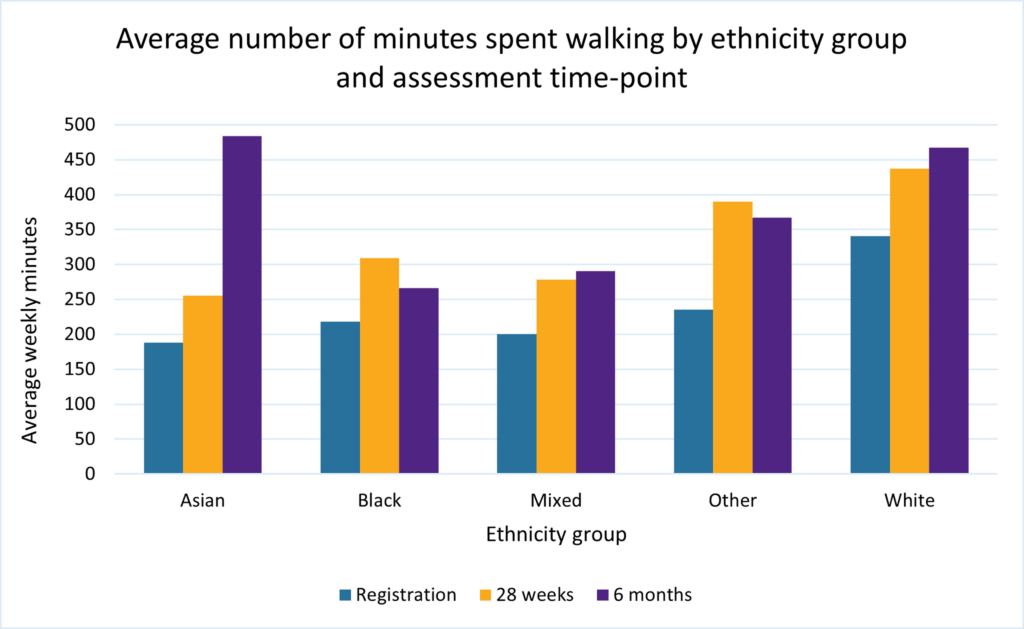

Activity time by ethnicity

Walking minutes increased most for Asian (from 188 to 484 minutes) and White (from 235 to 367 minutes) participants between registration and 6 months. Average walking time increased for Black and Other participants between registration and 28 weeks but decreased slightly between 28 weeks and 6 months. This is illustrated in Figure 6.

Moderate or vigorous activity time increased between all assessment points for Other ethnicity and White participants. Moderate or vigorous activity increased between registration and 6 months for all ethnic groups, however the time decreased slightly between registration and 28 weeks for Asian, Black and Mixed participants. This is illustrated in Figure 7.

Activity time by area deprivation

Average walking time increased between registration and 28 weeks for participants in all IMD groups but decreased slightly for all IMD groups* except from IMD group 3. This is illustrated in Figure 8.

*Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), 2019 locally derived quintiles. 1=most deprived 5= least deprived areas

Activity time by BMI group

Participants across all BMI groups walked around 1.5-2 hours more per week at 28 weeks compared to registration. Walking time decreased for those in obesity class I and II between 28 weeks and 6 months but increased for overweight and obese class III groups. This is illustrated in Figure 9.

Participants in obese class II did more moderate or vigorous activity at 28 weeks with a slight decrease between 28 weeks and 6 months. Moderate or vigorous activity decreased for those overweight, in obesity class I (both very marginally) and obesity class III between registration and 28 weeks, however increased at 6 months.

Those in the overweight category reported an average of 93 minutes of moderate or vigorous activity 6 months. This is illustrated in Figure 10.

Feedback from participants

Feedback from participants was overwhelmingly positive. Of the participants who completed the Family Feedback form:

- 100% strongly or very strongly agreed that they had a positive experience of the service

- 100% strongly or very strongly agreed that they could trust the staff

- 100% strongly or very strongly agreed that they felt welcome

- 96% strongly or very strongly agreed that the staff understood their family’s needs

Some examples of feedback include:

I enjoyed my time at CAN…the team was friendly, easy to talk to and I didn’t feel judged, which is important because women who are a bit big do feel judged.

The midwife was extremely kind & helpful and has been supportive since our first conversation regarding the classes. My practitioner was a great course provider & was very knowledgeable and supportive. I had very clear weekly targets that felt manageable and achievable. I could ask questions & got clear answers. I had a fantastic experience – thank you.

A lot of effort made to make session relatable to people of different backgrounds.

This service was excellent. It was tailored to my needs and was relayed in a way that allowed me how to use what I was taught practically.

The practitioner was very knowledgeable and explained every topic we discussed each day in detail. This helped me to understand how best to look after myself and my unborn baby by eating healthily, which is very important. Also with the programme, I have knowledge on the best food that is good for my family as well, by making a healthy choice.

She was very knowledgeable, and she encouraged me to reach my goals without putting pressure on me or making me feel bad if I don’t meet them. I learned a lot through this programme, and I was able to better my eating habits to lower my high blood pressure.

Starting Solids workshops

From October 2022 – March 2024, the HIFs delivered 54 starting solids workshops that 259 people attended. All workshops were delivered face to face. Of the participants who provided data about their ethnicity (n = 92), 58% were White, 12% were Black, 12% were Asian, 12% were Multiple, 5% were other and 1% preferred not to say. The number of attendees at each session ranged from 1 – 14.

Data was self-reported by participants who attended workshops. Participants were asked to answer a series of questions about infant feeding and starting solids before attending the workshop (baseline) and again after attending the workshop (completion).

Confidence

After the workshop, participants reported increased confidence on 11 topics related to starting their babies on solid food. Increased confidence scores were as follows:

- When to start solid foods: 60% increase

- Recognising signs of readiness: 75% increase

- How to keep my baby safe: 231% increase

- How much solid food to give: 360% increase

- Recognising signs of fullness: 248% increase

- Introducing finger foods: 314% increase

- Encouraging baby to try different foods: 56% increase

- Balancing milk and solids: 115% increase

- Preparing meals for baby: 83% increase

- Making mealtimes enjoyable: 84% increase

Knowledge

After the workshop, more respondents recognised all three clear signs of readiness. Increased scores were as follows:

- Baby can stay in a sitting position and hold their head up unsupported: 15% increase

- Baby can pick up food and put it in their mouth by themselves: 36%

- Baby can move food to the back of their mouth and swallow it: 70% increase

One participant said this:

The information given about when to start finger foods and when they have had enough, was what I found to be the most useful part of the course.

4.1 Successes

The LEAP CAN service aimed to achieve change by supporting women with a BMI of ≥25 with improved nutrition and increased physical activity during pregnancy. The service was well-established and developed close links with many other LEAP services, which was important for the LEAP programme overall.

Personalised and culturally appropriate support

Throughout the CAN service, the team ensured that the content was tailored to the woman’s everyday diet. Starting with the initial recruitment conversation, the importance of food and its cultural significance in everyday family life was acknowledged.

The main CAN message was not about altering women’s diets significantly; instead, the focus was on weekly incremental food swaps that complemented their normal diet. These messages were emphasised with examples of food swaps and recipes in the participant manual and through the tailored information given by HIFs in the individual sessions.

The content of the participant manual was regularly reviewed to ensure it represented the different cultures of women taking part. Women often commented that they particularly enjoyed this aspect of the service and found it useful as they felt it was suited to them and their families.

If a woman’s cultural food preferences were not found in the participant manual, the HIFs did additional research to ensure they could provide tailored, evidence-based information according to her needs.

The HIFs were sensitive to both women’s previous relationship with food in addition to recognising the difficulties they may experience in pregnancy e.g. nausea or food aversions.

Flexible appointments

Another success of the service was the high number of women who completed it. The one-to-one nature of the CAN sessions and the timings of the appointments to suit women’s busy schedules are important factors in contributing to this success. Since the offer of group sessions was not well-received, as described in section 3.7, many CAN appointments were delivered in the evening (home visit or phone), which women said fitted better into their schedules. The flexibility of the CAN team to adapt to times that suited women contributed to the successful completion rate.

Midwife/Health Improvement Facilitator delivery model

The midwife/HIF team model was another successful element of the CAN service, and the skill mix was important for the delivery of the service.

Women can often feel anxious in pregnancy and overwhelmed by the array of information given by families, friends and the internet. The first appointment with the midwife gave women the opportunity to ask questions. It provided reassurance and essential information about the benefits of the service before delivering individual tailored support by the HIFs.

By working together, midwives were able to advise and reassure the women and supervise and support the HIFs who were not clinically trained.

While a midwife is needed to oversee service delivery, it is not necessary for a midwife to deliver the individual sessions. This is therefore a more affordable service to implement and deliver.

Providing a joined-up offer to local families

As one of the first services to be commissioned and delivered by LEAP, CAN worked closely with other LEAP services, which is important as LEAP provides integrated support for families.

CAN referred/signposted women into the Breastfeeding Peer Support service, Healthy Living Platform (for community food support), Baby Steps (for parenting support) and PAIRS (for parent-infant mental health support). Additionally, the service also distributed oral health packs, containing toothbrushes, toothpaste and free-flow cups, at the 6-month postnatal visit.

Using the CAN team to deliver HENRY’s starting solids workshops to CAN clients as well as to parents/carers living in Lambeth was a logical complement to the aims of the CAN service, and the service was very well received.

Having sensitive conversations

Conversations about maternal weight need to be led confidently and sensitively. Women were identified at booking and contacted via letter, phone and text. As most women were recruited by phone calls, first conversations were very important.

During these first phone calls the CAN midwife acknowledged the difficulties that everyone faces in everyday life in relation to diet and activity. They explained that pregnancy symptoms can increase these difficulties. They also stressed that CAN is not an authoritarian service. Women will not be told what to eat. Instead, the service works within their everyday diet, celebrating and valuing cultural foods.

The HIFs used several approaches and techniques to engage women positively so that a trusting relationship could be established. These include:

- Re-emphasise that CAN is not a weight loss programme or a diet

- Use non-judgmental tone; avoid stigmatising language

- Encourage open conversations

- Provide women with information about Gestational Diabetes and BMI and explain the benefits of healthier eating and physical activity

- Emphasise that drastic changes aren’t required: break down into small steps

- Enable woman to own the process by asking, ‘are there any areas of your diet you would like to make changes to?’

- Use motivational interviewing, active listening and Make Every Contact Count (MECC) training and skills

- Understand the woman’s life e.g. by asking about her job, children, housing

This approach helps the woman feel understood and builds rapport. It also allows the practitioner to tailor the service to each individual woman’s circumstances.

In relation to engaging women positively about food, the HIFs:

- Celebrate healthy choices women already make

- Ask about personal preferences and typical diet

- Utilise African and South Asian Eat Well guides

- Give choices about portion size, healthier cooking techniques and healthy food swaps

- Give ownership to women: ask what they would like to focus on each week

- Celebrate changes that are made

In relation to engaging women positively about physical activity, the HIFs:

- Emphasise that women can do physical activity during pregnancy and provide information about safe exercise

- Celebrate physical activity woman is already doing

- Start where they are and build up from there: break down the goal into manageable weekly progressions and ensure it fits around their day-to-day life

- Help women see patterns by reviewing step count at each session*

*This helps to understand patterns of behaviour, e.g., if step count is related to weather or emotions

The HIFs were also aware of influence of the wider determinants of health, and supported women accordingly. Some examples of this include:

- If a woman lives without a kitchen, she can be supported to make healthier choices, e.g., walking to the shop

- If a woman has no autonomy over the kitchen or what she is given to eat, a bit of knowledge can help her to make better choices in an unhealthy situation

- If a woman cannot control the food she is given to eat, she can exercise more

- Being aware of religious practices, e.g., Ramadan, where a woman wakes up early to prepare food

- There is always something you can do, no matter how small – start & build from there

4.2 Challenges

Challenges in delivering the LEAP CAN service include:

Recruitment

Recruitment to weight management services and programmes in pregnancy can be difficult.

Addressing weight in pregnancy can be very sensitive for some women and conversations about the subject need to be approached with care. The initial recruitment telephone call was the most effective means of engaging women with CAN. However, there were many women who never answered the phone, so the team were unable to have an in-depth conversation about the benefits of the service with them.

Ideally, every eligible woman would have a conversation with their clinical midwife about the benefits of taking part in CAN. However, given that general midwives were not necessarily aware of which women lived in the LEAP geographic area, the CAN team took on the sole responsibility of recruiting women into the service. Rolling out a similar service in a wider geographical area would enable maternity staff to feel more confident about signposting women to the service.

Covid 19

As for all LEAP Services, the Covid 19 pandemic disrupted the delivery of CAN.

Four of five CAN team members (midwives and HIFs) were redeployed into the wider NHS from April 2020 to July 2020, which meant that service delivery was halted, and no new women were recruited during this time.

Existing CAN clients completed the service over the phone and no women had their 2nd midwife appointment during this time, which had impacts on data collection. New women were not offered the service during this time.

Women dropping out of sessions and /or follow up appointments

Pregnancy can be very stressful for some women, particularly if they have extra obstetric appointments, and women often cited external pressures for deciding to leave the service early.

Some women dropped out at the 28 week and 6-month postnatal appointments. This meant that for these women, we were unable to obtain IPAQ measurements, gain feedback about the service or signpost to other LEAP services.

5.0 Sustainability and next steps

Throughout the lifetime of delivering CAN, LEAP was asked to deliver different presentations about the CAN service model. These requests came from the Association of Directors of Public Health children and young people’s London network (two different presentations) and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (three different presentations).

Repeated interest in the LEAP approach to supporting maternal weight demonstrates an appetite for learning about this innovative service delivery model at the local and national levels. Future funding for CAN was not secured and the service closed in March 2024.

The materials developed for CAN’s sister service, Pregnancy Information on Nutrition and Exercise (PINE), have been adopted by Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and will continue to be available to all pregnant women on their website.

6.0 Key messages and reflections

- The CAN service was acceptable to women living in the LEAP area, and tailoring the service to women’s cultural preferences ensured that the service was culturally appropriate

- CAN successfully reached LEAP’s priority population as most participants were from Black, Asian or Multiple Ethnic groups and lived in areas of deprivation

- CAN participants increased both their physical activity levels as well as the time spent in physical activity during and after pregnancy

- Establishing trust, skilfully leading sensitive conversations about weight, and providing evidence-based information about the benefits of the service supported recruitment, retention and overall satisfaction with the service

- A flexible approach to delivering sessions, including offering evening and weekend appointments, was key for ensuring the service could fit into women’s busy schedules and supported enrolment and completion of the service

- Maternal weight has been identified as a high impact area, as well as a modifiable factor for preventing infant deaths in London

- There is system-wide interest in LEAP’s approach to implementing CAN. More work should be done to ensure funding is available for widespread implementation of this preventative model.

7.0 Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nina Khazaezadeh and Eugene Oteng-Ntim for their support in developing LEAP’s CAN service and for championing it over the years.

We would also like to thank Deborah Ricketts, Rebecca Heath, Sonia Laing and Deborah Iyinolakan for their years of dedication as Health Improvement Facilitators, and for sharing with us the different approaches and techniques they used to skilfully lead sensitive conversations about maternal weight.

8.0 Appendices

Appendix A, CAN invitation letter

Dear XXXXXXXX,

Congratulations on your pregnancy.

We are inviting you to join us in a free specialist Community, Activity and Nutritional programme which is part of your routine midwifery care.

This programme has been designed to enhance your nutritional needs and to support your physical activity during your pregnancy. It is only offered to women living within the Lambeth wards of Coldharbour, Stockwell, Tulse Hill and Vassall.

The programme aims to support you to make healthy lifestyle choices during pregnancy and beyond and to enhance both your and your baby’s health. This programme complements your usual diet and is suitable for all cultures. We are very flexible and can work around your and your family’s schedule.

Please call or email for further information and/or to book your appointment.

Best wishes

Shelia O’ Connor

LEAP CAN Midwife- KHP

King’s College NHS Foundation Trust

Guy’s & St. Thomas’ Foundation Trust

Appendix B, The Community, Activity and Nutrition leaflet

Appendix C, text message sent to participants

Hi,

I am following up on a letter/leaflet we sent you about the LEAP CAN programme.

LEAP CAN is a community nutrition programme for pregnant women in the LEAP area with a BMI of > 25.

The appointments can be face to face or over the telephone and can be arranged at a time to suit you.

If you are interested and/or would like further information, please text YES.

Appendix D, CAN participant manual

Example pages from the participant manual:

Appendix E, CAN logbook

Appendix F, example pedometer