April 2024

LEAP's oral health promotion service

April 2024

LEAP’s oral health promotion service

1.0 Executive Summary

This Learning Journey tells the story of Lambeth Early Action Partnership’s early years oral health service. Learn about the children and families we prioritised, the sectors and local professionals we involved, the barriers we overcame and the evidence that drove our planning and implementation.

Authors

Angharad Lewis, Public Health Officer, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

Claire Benzies, Oral Health Promoter, King’s College Hospital.

Carla Stanke, Public Health Specialist, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

Who is this for?

These learnings provide a blueprint for those responsible for improving oral health outcomes in their communities. This report will be useful for anyone with a professional or academic interest in dental public health and early childhood development.

The background

Despite improvements over the past 20 years, almost a quarter of 5-year-olds in England have tooth decay. Children are at more risk of developing tooth decay if they:

- eat a poor diet;

- brush their teeth less than twice per day with fluoride toothpaste;

- reside in areas of greater deprivation.

Poor oral health can have negative impacts on general health, wellbeing, and attainment. Dental neglect may also indicate wider safeguarding issues.

LEAP works in areas in Lambeth that have greater inequalities for young children than the rest of the borough. Evidence demonstrates that the more deprived a community is, the higher the risk of tooth decay. There is also evidence that less well-off parents have more difficulty gaining access to an NHS dentist.

Before 2017, there was no structured, early years, oral health promotion service within the LEAP areas of Lambeth. The LEAP oral health service was designed to meet this need as part of our Diet and Nutrition work. We used a strong evidence base that was well-aligned with national policy and priorities. We also involved experts, parents and key community service providers along the way.

We focused on the provision of toothbrushes and paste, and supervised tooth brushing in childcare settings. We delivered training for local early years practitioners and oral health promotion at community events. We also worked with local dental practices to increase dental check-ups for children under one year old.

Headline numbers

Key statistics you can read more about in our full Learning Journey:

- 6,000+ toothbrush packs were distributed.

- 31 childcare settings were trained to deliver supervised toothbrushing.

- 818 children reached by our supervised tooth brushing service (78% age 0-3).

- 77% of those children were living in the most deprived areas we cover.

- 64% of those children were identified by their parents as Black, Asian, mixed race or other.

2.0 Purpose of this document

LEAP developed this Learning Journey to capture the story of LEAP’s oral health service over its lifetime: from its inception to the end of its journey as part of the LEAP programme.

A key focus of a Learning Journey is on implementation: how the service was delivered and the different resources required to do this. Learning Journeys are service summaries, not service evaluations, and are part of a wider suite of LEAP research and learning projects designed to capture insights into our progress towards giving children in the LEAP area a better start in life.

Information contained within this report was taken from national policy and evidence as well as from a variety of internal LEAP documents including:

- service plans;

- theories of change;

- monitoring, evaluation and learning frameworks;

- quarterly narrative reports and service data reports;

- workforce and client feedback;

- minutes from service reviews and team meetings.

Learning Journeys were co-written between service leads and members of the LEAP team, and the Key Messages were based on high-level reflections drawn not only from the available data but also from insights gleaned over years of service delivery.

We will share our Learning Journeys with key stakeholders including the National Lottery Community Fund, local early years commissioners and public health colleagues, service delivery partners, families and via national public health networks as appropriate.

Our hope is that the learning from the LEAP programme can inform future commissioning and programming decisions and contribute to the wider evidence base about health-improvement interventions in the earliest years.

3.0 Background

3.1 What is LEAP?

Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP) is one of five local partnerships which make up ‘A Better Start’, a national ten-year (2015-2025) test and learn programme funded by the National Lottery Community Fund that aims to improve the life chances of babies, very young children, and families. LEAP is a ‘collective impact initiative’, which means that our services and activities link together and work towards shared goals to improve outcomes for very young children.

3.2 Why is oral health in the early years important?

Tooth decay is the most common oral disease affecting children in England, yet it is largely preventable.1 It is well recognised that oral health is essential to general health, wellbeing, attainment and quality of life, and impacts on an individual’s life course.2 Pain and infection can affect sleeping, eating, speaking, learning and socialising with other children, leading to failure to thrive and school readiness.3

Children in pain or requiring treatment may be absent from school or early years provision, and parent/carers may have to take time off work to care for them. Evidence shows that poor oral health may also be indicative of dental neglect and wider safeguarding issues.3 Dental neglect is defined as “the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic oral health needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of a child’s oral or general health or development”.3 Furthermore, children who have teeth extracted in hospital are treated under general anaesthetic which presents a small but real risk to life.3

3.3 Causes of poor oral health

Children are at more risk of developing tooth decay if they:

- eat a poor diet;

- brush their teeth less than twice per day with fluoride toothpaste;

- are from areas of greater deprivation.3

PHE uses the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) to define levels of deprivation. IMD measures relative levels of deprivation at a small-local-area level across England based on seven domains to produce an overall relative measure of deprivation. Deprivation is measured in a broad way to encompass a wide range of aspects of an individual’s living conditions.4

Eating a poor diet

At a tooth level, dental decay results from the destruction of the hard tissues of the tooth by acids produced in the mouth when bacteria in dental plaque metabolises dietary sugars.

Repeated and prolonged acid attacks will eventually cause the tooth surface to weaken, and a hole or cavity will form which may lead to pain and infection. The risk of tooth decay increases if a child’s diet includes foods and drinks (other than breast milk or infant formula), depending on the free sugar content. Free sugars include all added sugars in foods and drinks, and the sugars present in honey, syrups, fruit juices, smoothies and fruit juice concentrates.

Every child who has teeth is at risk of tooth decay, and children with a poor diet are at increased risk. In England, half of children’s sugar intake, around 7 sugar cubes a day, comes from unhealthy snacks and sugary drinks, leading to obesity and dental decay.5

A significant barrier to reducing sugar consumption is the obesogenic environment. An obesogenic environment refers to the role that environmental factors may play in determining both nutrition and physical activity; it is an environment that promotes high energy intake and sedentary behaviour. Factors that contribute to an obesogenic environment include the foods that are available, affordable, accessible and promoted; physical activity opportunities; and the social norms in relation to food and physical activity.6

Toothbrushing

It is well established that increasing the availability of fluoride for people and communities is effective at reducing tooth decay levels.7 Daily toothbrushing is the most common delivery system for fluoride.

A systematic review was conducted to determine the effectiveness and safety of fluoride toothpastes in prevention of dental decay in children and to examine factors potentially modifying their results. In this review, one study involving 2,008 children aged 6-9 showed a 37% reduction in dental decay in primary (baby) teeth.8

There is some evidence 9 10 that shows barriers to toothbrushing may include:

- false beliefs about the benefit of brushing teeth twice a day;

- lack of a social norm or other support for twice daily brushing;

- lack of time and emotional reaction from children;

- lack of knowledge of how to overcome the barriers;

- and parent concern about ingestion of fluoride toothpaste.

Deprivation

Poor oral health disproportionately affects socially disadvantaged people and groups. The risk of dental decay increases for those living in more deprived areas where the imbalance in income, education, employment and neighbourhood circumstances affect the life chances of children’s development.3

There is clear and consistent evidence for social gradients in the prevalence of dental decay, where children living in the most deprived areas experience more dental caries than children living in the least deprived areas.11

3.4 Understanding the level of need

While children’s oral health has improved over the past 20 years, almost a quarter (23.4%) of five-year-olds in England still had tooth decay in 2019; in 2022 this raised slightly to 23.7%.12 Moreover, each child with tooth decay will have on average 3.5 teeth with dental decay affected.12

A survey of three-year-olds in 2020 found that by age three, 10.7% had already experienced tooth decay, with on average three teeth affected.13 Furthermore, significant regional inequalities remain between and within boroughs.14

In 2019 to 2020 three-year-olds in the most deprived areas of the country were nearly three times as likely (16.6%) to have experience of dental decay than those in the least deprived areas (5.9%).13 It is of concern that inequalities in oral health are stark even by age three.

LEAP delivers services in parts of Lambeth based on local need, drawing on a range of local evidence that illustrates greater inequalities for young children in the LEAP area compared with the rest of Lambeth. In the LEAP geographic area, 43% of neighbourhoods are classified as most deprived and 68% of children live in very deprived households.4

Data for three-year-olds in Lambeth shows that 10.1% of children have experience of tooth decay, which is better than for London (12.7%).13

Hospital Episode Statistics data (a dataset that contains details about admissions, outpatient appointments and historical accident and emergency attendances at NHS hospitals in England) shows between 2018/19 and 2020/21, 300 per 100,000 children aged 0-5 years old in Lambeth were admitted to hospital for dental decay, compared to 221 per 100,000 in England.15

There is also evidence of a socioeconomic divide in terms of access to dentists. Nationally, the percentage of parents that had difficulty finding an NHS dentist was substantially higher among those with children eligible for free school meals (18%) than those whose children were ineligible (11%).16

Although there is currently no breakdown of oral health outcomes by ward in Lambeth, evidence demonstrates that deprivation is an indicator of increased risk of tooth decay.14 11 This could suggest that the LEAP areas have higher rates of tooth decay than the rest of Lambeth.

3.5 Evidence-based approaches

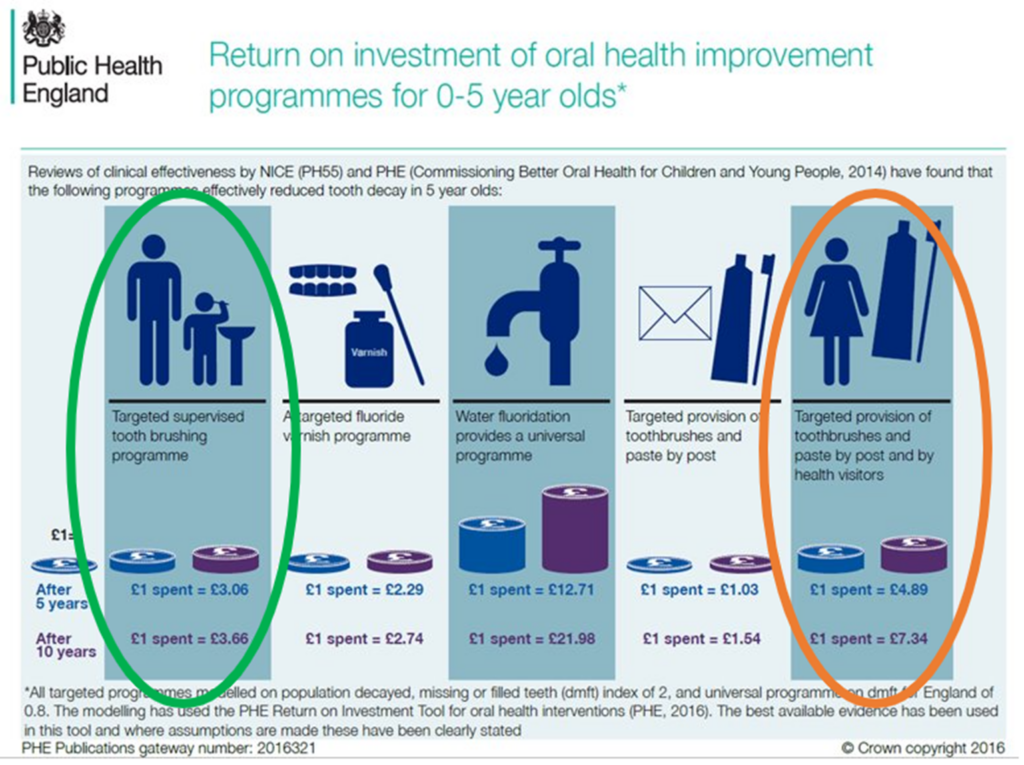

PHE published an evidence-informed toolkit for local authorities which includes an evidence review of population based oral health improvement programmes 17 as well as an oral health intervention return on investment tool.18

In addition, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) reviewed the clinical effectiveness of oral health improvement programmes.19 Both reviews found that the following programmes effectively reduce tooth decay in five-year-olds and represented a good return on investment (listed in order of greatest impact first):

- water fluoridation;

- targeted provision of toothbrushes and paste by post and by health visitors;

- targeted supervised toothbrushing (STB);

- a targeted fluoride varnish programme;

- and targeted provision of toothbrushes and paste by post.

4.0 LEAP’s oral health service

In 2017, when we were designing the portfolio of LEAP services, there was no structured, early years, oral health promotion within the LEAP area.

King’s College Hospital Community Specialist Dentistry team provided oral health advice to children in priority primary schools in Lambeth, but there was no universal early years oral health promotion locally. To respond to the identified gap in service delivery, whilst also taking into consideration the high rates of inequalities in the area, LEAP included an Oral Health Promotion service as part of its Diet and Nutrition strand of work.

LEAP commissioned King’s College Hospital (KCH) to deliver its early years Oral Health Promotion service, which consisted of one full-time NHS band 6 Oral Health Promoter based in the Community Special Dentistry team (CSDT), with strategic oversight provided by CSDT management.

A service design process was undertaken involving King’s Dental Health Institute, LEAP parents, Lambeth Children’s Centre workers and Health Visiting leads. Service design activities included:

- focus groups with King’s Dental Health Institute and LEAP parents to capture views about looking after children’s teeth and experiences of visiting the dentist;

- a workshop with practitioners to test the service idea, including service outcomes;

- and face-to-face meetings with the Local Dental Committee (which consists of local NHS General dental practitioners as well as secondary care and community representatives) and members of the Lambeth community dental team to gather expert views on what works locally, how dental practices link with the community and how the LEAP enhanced service will sit alongside and enhance oral health for the early years.

Co-production activities gathered insights which informed the design of the service. For example, local parents felt that dentists needed to be more child friendly; family information sessions about oral health should be held at community events; and dentists should have more direct links with other health professionals like health visitors.

Based on PHE’s return on investment calculations 18 and insights gathered during the service design phase, LEAP’s oral health service focused on:

- Targeted provision of toothbrushes and paste by post and by health visitors

- Targeted supervised toothbrushing

To address the barriers to toothbrushing mentioned in section 3.3, the service also delivered the following activities:

- Workforce training for local early years practitioners

- Oral health promotion at local community events

- Partnership working with local dental practices to increase dental check-up for children under one year old

We will now expand on each of these elements of LEAP’s oral health service.

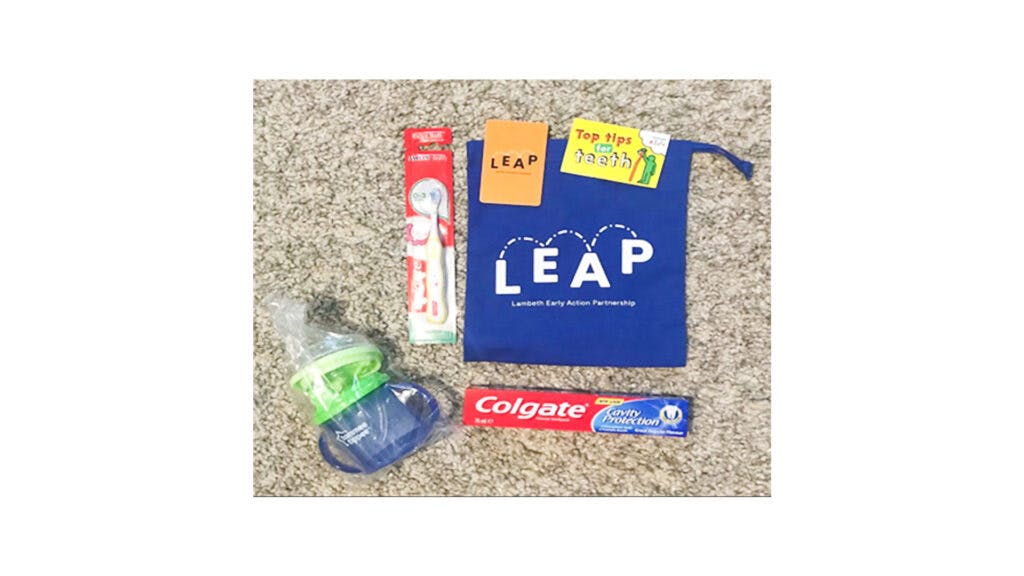

4.1 Provision of health packs

Targeted and timely provision of free toothbrushes and toothpaste can encourage parents to adopt good oral health practices and start toothbrushing as soon as the first teeth erupt.

LEAP developed two different oral health packs for distribution to local families:

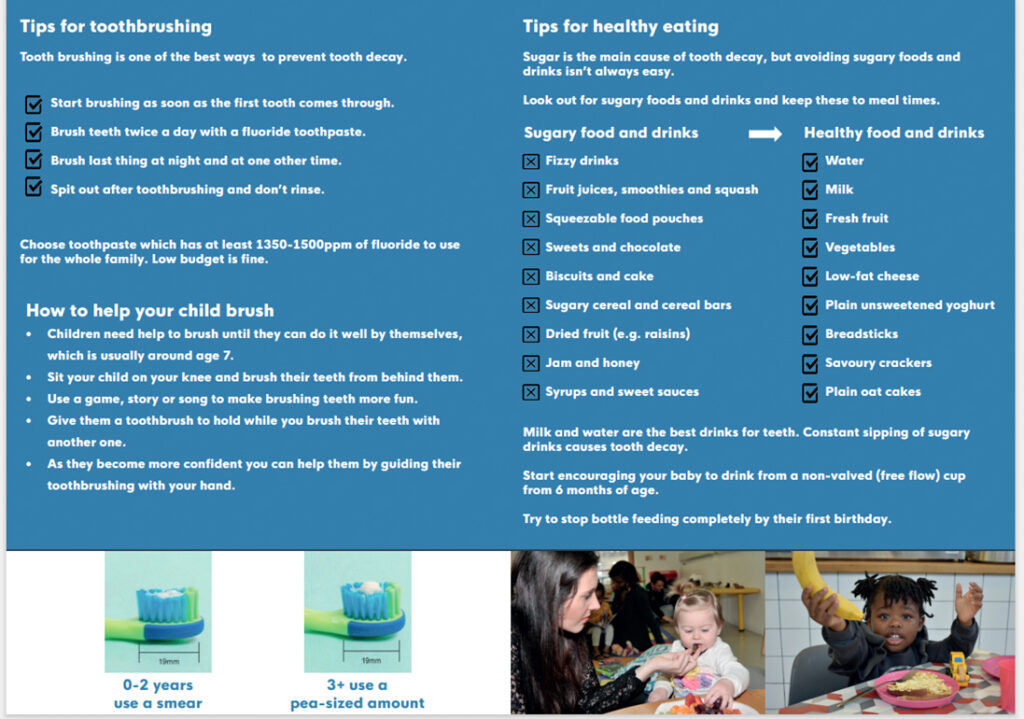

- A basic pack containing a toothbrush and a tube of generic family (instead of child-branded) fluoride toothpaste containing 1450 ppm of fluoride, top tips for teeth health messaging card and general information about the wider LEAP programme.

- An enhanced pack containing a toothbrush, generic branded family toothpaste containing 1450 ppm of fluoride, a free flow cup (a cup that allows liquid to flow freely without needing to be sucked), top tips for teeth health messaging card and general information about the wider LEAP programme.

Generic family toothpaste was included in the oral health packs as evidence shows that family/adult toothpaste is safe for children of all ages 20, and that although children’s toothpaste has become more popular it is not necessary to use it.

This message was promoted to local families to ease the process of buying toothpaste for the family and reduce costs as families would not need to buy multiple types of toothpaste. We included a free flow cup in the enhanced oral health packs as using a cup without a teat helps children to sip (and not suck) and is better for their teeth.

4.2 Supervised Toothbrushing Programme (STB)

The Oral Health Promoter approached childcare settings and childminders in the LEAP area (as well as those in nearby surrounding areas) and offered support to participate in the STB programme.

STB programmes have been found to prevent tooth decay by teaching children how to brush their teeth and encourage tooth brushing at home. Children also benefit from brushing their teeth with fluoride toothpaste once a day while at their early years setting, which is especially important for those who may not regularly brush their teeth at home.

Participating settings received training from the Oral Health Promoter which covered:

- LEAP’s oral health strategy;

- child oral health and its impact nationally and locally;

- key evidence-based messages for oral health prevention;

- strategies to support families to adopt behaviours for oral health, including signposting to NHS dental services;

- how the STB programme works in practice;

- and demonstration and participation in the STB process.

Each setting received the resources needed to take part: toothpaste, toothbrushes. a toothbrush bus which store toothbrushes, and parent information sheets and consent forms.

Settings received a comprehensive STB toolkit which provided an overview of:

- evaluation processes;

- data management and security;

- resources;

- effective practice;

- STB method;

- and infection prevention and control.

Settings also received a quality assurance checklist to be completed termly and a service review checklist to be completed annually. The Oral Health Promoter provided settings with ongoing support and carried out termly and annual audits (examples of STB resources are included as appendices).

4.3 Working in partnership with local dental practices

The service worked with LEAP area dental practices, as well as those in the surrounding areas, to increase local family’s access to family friendly dental practices as part of the Dental Check By One campaign.

Local dental practices were offered a one-hour CPD accredited lunch and learn training where they were provided with guidance, resources and ongoing support for working with very young children.

Dental practices were invited to become a family friendly practice which LEAP families could be signposted to and were encouraged to promote fluoride application to new registered patients (if applicable).

4.4 Workforce development training

The Oral Health Promoter developed a Continuous Professional Development (CPD) accredited one-hour training course for the local early years workforce, such as Health Visitors and nursery practitioners.

The aim of the training was to enable practitioners to give consistent evidence-based oral health messages and advice to local families regarding early years oral health.

Content of the training was taken from different evidence-based sources. The desired learning outcomes for attendees were:

- better understanding of current evidence based oral health messages in England;

- strengthened knowledge on free sugars in food and drinks;

- strategies to support oral health for babies and young children;

- and increased knowledge on Dental Check by One and fluoride varnish.

4.5 Community oral health promotion

Throughout the LEAP programme the Oral Health Promoter attended a variety of community events.

They provided local families with informal, friendly advice on how to look after their family’s oral health using easily accessible evidence-based messages, signposting to resources and local family friendly dental practices. These promotional activities used fun, child-centred activities including stories, singing and puppets.

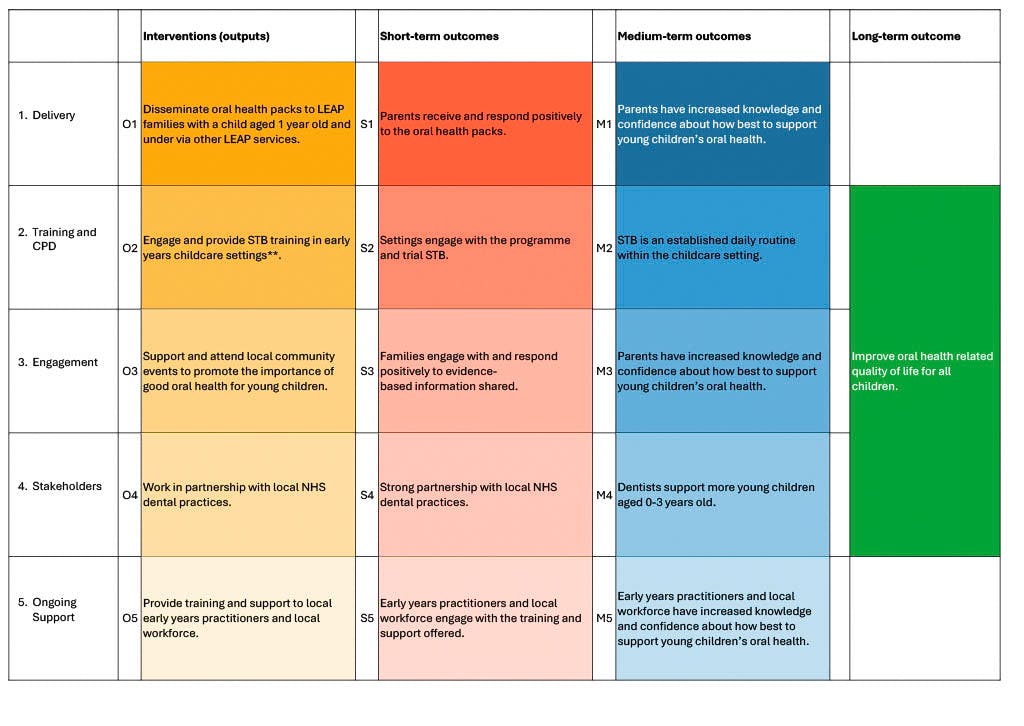

LEAP developed a theory of change (Figure 1) for the service, with the key desired outcome of improving oral-health-related quality of life for all children in the LEAP area by achieving the following four medium-term outcomes:

- increasing parent’s knowledge and confidence about how best to support young children’s oral health;

- establishing supervised toothbrushing (STB) as part of the daily routine within childcare settings;

- increasing the number of children aged 0-3 years seen by a dentist;

- and increasing the knowledge and confidence of early years practitioners about how best to support young children’s oral health.

Figure 1: LEAP’s oral health service theory of change

Oral health service: Supervised Tooth Brushing, Oral Health Packs, Dentist Engagement

What is the service?

The oral health service promotes good dental practice for early years children. Key oral health messages are promoted through community activities and workshops. Supervised toothbrushing (STB) is supported in PVI childcare settings. The oral health service also works with dentists to support them to be child friendly and to promote early dental attendance and uptake of fluoride varnish.

Who is eligible?

- PVI childcare settings and their practitioners.

- Dentists who are interested in promoting child-friendly practices.

4.6 Outcomes, reach and feedback

Since the STB programme began delivery in 2019, demographic data was collected about the children who participated, as well as data about the practitioners who were trained to deliver STB.

Based on this data it is possible to reflect on three of the four medium-term outcomes identified in the service’s theory of change (Figure 1).

Over the lifetime of the STB service:

Medium-term outcome 2: supervised toothbrushing is an established daily routine within the childcare settings

- 31 childcare settings were enrolled and trained to deliver STB (16 childminders + 15 nursery settings, nearly 100 people altogether).

- 818 children engaged with the LEAP STB programme; of these 42% lived in the LEAP area and 78% of children were age 0-3.

- 64% of children were identified by their parents/carers as Black, Asian, mixed race or other ethnicity, compared with 76% in the wider LEAP population.

- 77% of children lived in the two most deprived quintiles of deprivation, compared with 91% in the wider LEAP population.

- 26% of children had English as an additional language.

One practitioner delivering STB offered this feedback:

Children love to do it as a group activity after lunch. Going really well, the children love it.

Medium-term outcome 4: dentists support more young children aged 0 – 3

- Over the lifetime of the service 18 children under age 2 were supported to attend a dentist for their first visit

Thank you for today, it was a very good day. Thanks for the information, I think it was perfect.

Medium-term outcome 5: early years practitioners and local workforce have increased knowledge and confidence about how best to support young children’s oral health

- 12 CPD-accredited oral health training sessions were delivered to 96 members of Lambeth’s early years workforce over the lifetime of the service

Feedback provided by 12 people who completed the training was positive. Attendees reported feeling more knowledgeable about current evidence-based oral-health messages as well as strategies to support the oral health of babies and children.

No data was collected for medium-term outcome 1 or 3: parents have increased knowledge and confidence about how best to support young children’s oral health.

Other outcomes: oral health packs

- 3,400 enhanced oral health packs were purchased and distributed

- 2,795 basic toothbrush packs were purchased and distributed

Health visitors initially distributed packs. They were based at health centres with the highest numbers of LEAP families during 8-12 month reviews. Later in the programme, packs were distributed through different LEAP services.

Enhanced oral health packs were distributed via Baby Steps, Community Activity Nutrition (CAN), Caseload Midwifery, Family Nurse Partnership, Breastfeeding Peer Support, Enhanced casework for domestic abuse service and LEAP HENRY Starting Solids workshops.

Enhanced oral health packs were also included in emergency food parcels that formed part of Lambeth’s early response to Covid-19. Basic toothbrush packs were distributed through LEAP’s Overcrowded Housing service, Doorstep Libraries and at LEAP community engagement activities. Materials were sourced from The Honest Tooth company.

Other outputs: community engagement activities

- 283 community events were attended by the Oral Health Promoter who provided oral health support and advice to local families

It has been such a pleasure to have Claire come as a guest spot to so many of our Baby Steps postnatal sessions, where parents and babies have benefited from all the oral health information delivered directly from an experienced dental nurse. They always really enjoyed the presentations and the free gift pack, to set them on their baby’s oral health journey with the best start! Thank you so much Claire for supporting Baby Steps families!

Attending has brought my knowledge up to date and enabled me to signpost parents to appropriate information

Long-term outcome

The LEAP oral health service sought to improve oral-health-related quality of life for all children it reached, as outlined in the theory of change (Figure 1).

The service, its theory of change, and the associated long-term outcome was evidence informed. The literature 19 17 18 suggests that targeted population-level oral health improvement programmes can have a positive impact on oral health in the early years.

Existing population measures make it difficult to assess LEAP’s oral health impact. National oral health surveys do not provide ward-level data, and whilst hospital data on tooth extractions is available at ward level and shows higher rates of extraction in Lambeth than the national benchmark, the numbers that these rates represent are relatively small. More years of data are needed to assess LEAP’s possible contribution to improving oral health at the population level.

LEAP delivered an oral health service that was well-aligned to national policy and underpinned by robust evidence. Over 800 children were supported to brush their teeth with fluoride toothpaste every day whilst at nursey, and thousands of toothbrush/toothpaste packs were circulated. As population-level data is currently unavailable it is not possible to assess the extent to which the service achieved its long-term outcome. However, using qualitative feedback we are confident that this evidence-informed and high-profile service has made a positive contribution to the oral health of the children it engaged.

4.7 Successes

LEAP’s oral health service involved a diverse range of interventions which aimed to achieve change at an individual and systems level. The service was well-established and well-known across the LEAP programme and the wider Lambeth early years sector and has made important achievements.

Providing a joined-up offer to local families

Through working in close partnership with other LEAP services, the oral health service was able to establish a joined-up local offer to families.

The service provided hundreds of young children with oral health packs thereby increasing access to fluoride, use of free flow cups and evidence-based oral health messages, all of which support positive oral health behaviours to be formed from the earliest age.

Despite initial challenges with distribution through health visitors, we were able to adapt and implement a more feasible method of distribution through LEAP services – thus enabling greater linkage between LEAP’s portfolio of services and consistent oral health messaging across the LEAP programme.

The service also supported the response to the Covid-19 pandemic by supplying oral health packs alongside emergency food parcels, which were distributed to local families with young children via one of LEAP’s services, Healthy Living Platform, as part of the Lambeth emergency food response scheme.

Furthermore, as an approachable and easily accessible member of the LEAP team, the Oral Health Promoter was able to answer ad-hoc dental queries from families and other practitioners and make referrals to specialist dental teams. This resource was invaluable in supporting other LEAP services and establishing clear pathways of support which otherwise may not have been so easily accessible.

Engaging the local community

LEAP’s Oral Health Promoter made connections with a variety of local community organisations. She attended many community events, providing families with informal advice on how to look after their children’s teeth using fun, child-centred activities including tooth-based stories, singing and puppets.

The Oral Health Promoter was well-known and valued by the local community. Children enjoyed the activities, and she was asked to attend many community events as a result.

Engaging and enrolling several local early years settings and childminders onto the STB programme was an important achievement. This was especially important considering the sector wide pressure on settings due to staff shortages, limited funding and breadth of responsibilities which settings have to meet.

The Oral Health Promoter was successful in engaging settings and childminders through tailored and sustained engagement. They took into consideration the pressures on settings and worked flexibly to make the process as simple as possible through the provision of all necessary resources, consent forms, protocols and provision of ongoing ad hoc support.

For settings that hadn’t participated in a STB programme before, the process could seem overwhelming, however once they implemented it, many staff realised it was simpler than it appeared. Two aspects were central to this process:

- Building relationships with settings

- Continuing to emphasise the importance of oral health in the early years whilst making clear links to how the STB programme could aid settings’ commitment to supporting oral health – as outlined in the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and other wider national policies.

Workforce development

Workforce training was delivered each quarter from September 2018 until June 2022. This training was aimed at the local early years workforce, such as health visitors, nursery staff and children centre practitioners.

Across the early years workforce there is an expectation on practitioners to attend CPD accredited training as part of their professional development. As a CPD accredited training provider, there was sustained interest in LEAP’s Oral Health training and attendance across the workforce.

We also worked with the local authority to promote the training to local early years settings in response to the introduction of oral health within the EYFS. This training transferred to an online offer in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Innovation in service delivery

The oral health team piloted several innovative projects throughout the course of the LEAP programme.

To increase the number of children having their first dental check by age one, as part of the national Dental Check by One campaign, LEAP’s Oral Health Promoter developed and piloted a unique method of engagement. A dedicated slot at a LEAP-area dental practice was secured and a stay and play session at a nearby children’s centre was provided and promoted to local families. LEAP’s Oral Health Promoter escorted families from the stay and play to the dental practice and helped them register their child and attend their first check-up.

This dynamic approach supported 18 families to register their child at a local dental practice. Given the evidence underpinning the importance of early intervention, e.g., campaigns like Dental Check by One 21, with more time and buy-in from local dentists this intervention could be further developed and expanded to other areas.

A joint project combining Natural Thinkers22 (a programme that supports teachers and practitioners in connecting children with nature through practical activities) and the Oral Health Promotion team was piloted to combine outdoor play with oral health promotion. It was based on a similar project run by Roehampton University for Key Stage 2 children. The LEAP team adapted this session for the early years.

The team’s Gummy Gardeners session lasted one hour. It included 30 minutes of outdoor play, exploring nature and taking part in fun activities in the children’s centre garden, facilitated by early years teachers and gardener. This was followed by a 30-minute session for parents where LEAP’s Oral Health Promoter shared top tips for looking after little teeth and gums.

This model of partnership working, which integrated early years oral health messaging within an early years play activity, was well-received by parents and could be piloted in other areas to better understand the impact on families who participated.

Supporting wider oral health work

The LEAP Oral Health Promoter also supported LEAP’s involvement in wider oral health public health work. They supported the development and delivery of an oral health survey designed to gather baseline data about the oral health status of children in LEAP-area childcare settings. The Oral Health Promoter worked with Public Health England (PHE) and King’s College Hospital (KCH) to help establish the sampling strategy as well as with data collection during the survey itself.

The Oral Health Promoter also supported a public health MSc student to design and deliver a survey about the oral health behaviours of parents of 2 and 3-year-olds. Additionally, they helped to engage parents during community events which ultimately improved response rates to the survey. Based on survey responses (n = 113) the key recommendations for LEAP were to:

- promote first dental check by one year old;

- support parents to manage children’s behaviour to enable them to brush regularly and effectively;

- educate and support parents about the importance of an adult brushing children’s teeth until they are at least seven years old;

- and enhance the motivation of parents to visit the dentist.

LEAP’s oral health service promoted the uptake of the first Dental Check By One. By attending community engagement activities, the Oral Health Promoter supported parents to better look after their children’s teeth by providing evidence-based information and advice.

4.8 Challenges

Challenges in delivering the LEAP oral health service include:

Data collection

Data collection was a significant challenge in the provision of oral health packs via the health visiting service, due to limited capacity. A number of solutions were attempted but it proved to be unfeasible to continue.

In early 2020 the decision was made to provide the packs via LEAP services instead, to families with children around 6 months of age. PHE recommended that oral health packs should be distributed by health visitors or by post.18 LEAP decided not to distribute packs via post as we had an existing robust distribution network with a wide reach through LEAP’s portfolio of services.

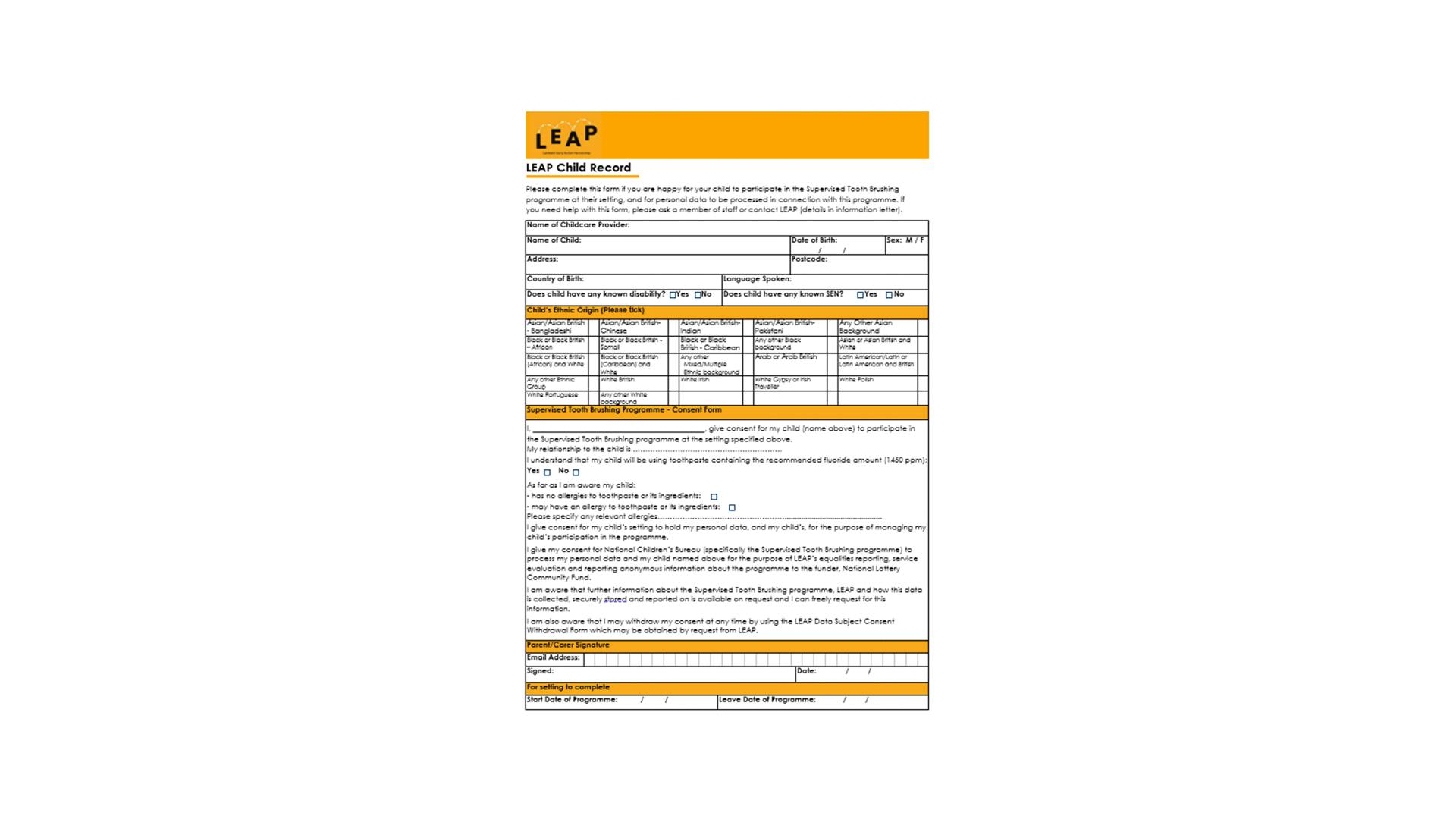

The consent form used for the STB programme presented a challenge for some services due to the amount of data necessary to collect. It was not easy to read, especially if English was not the parent’s first language. In response to this, we adapted the form to make it easier to read, highlighting certain areas in yellow to make clearer.

Engagement

Engaging local NHS dental practices to be more child friendly was a challenge throughout the programme. Several attempts were made to engage them, utilising a variety of methods such as sending letters, emails, phone calls and face-to-face visits to the practices. None of these methods resulted in any uptake of our offer of partnership working. This was likely due to wide-ranging barriers, including at the time, the Covid-19 pandemic through which access to dental care had been severely restricted.

Although there was success in engaging settings and enrolling them onto the STB programme, it was challenging for other settings. Sector-wide pressures on early years settings, including widespread staffing shortages, likely contributed to settings feeling unable to participate.

Covid-19 pandemic

As for all LEAP services, the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted the delivery of the oral health service. Closure of childcare settings meant the STB programme was paused. Later when settings re-opened, infection control measures meant that the STB protocol needed to be adapted to ensure the risk of contamination between children was limited.

Delivery of oral health packs to families via LEAP services was also impacted. These services were not functioning due to staff redeployment or because staff were not able to access the packs at the LEAP main office. The Oral Health Promoter was also redeployed into the wider NHS as part of the pandemic response for at least one quarter, which meant all service delivery halted, including workforce development training.

Resources

Towards the end of the service, there were difficulties in accessing resources such as toothbrushing buses – for storage of toothbrushes at early years settings – and toothpaste for distribution in oral health packs.

This was due to either discontinuation of certain products or national shortages due to global shortages. There was also a significant delay in the development and approval of the STB protocol, which required clinical sign-off from KCH, delaying the start of LEAP’s STB programme by six months.

5.0 Sustainability and next steps

A business case was developed outlining options for the sustainability of the oral health service.

A working group of relevant local stakeholders convened, including representatives from the Lambeth Public Health team, Lambeth Early Years and Parenting team, Lambeth Early Years and Out of School team and King’s College London Hospital (KCH) Community Special Dentistry Team. Throughout the course of these meetings, it emerged that responsibility for early years oral health is shared across different stakeholders, with complexities in relation to where leadership sits for this work.

It was decided that maintaining LEAP’s well-established STB programme was the priority in terms of sustainability. This was decided on considering the high cost of supplying oral health packs, alternative workforce training options and existing community oral health promotion via KCH CSDT.

Through LEAP-facilitated discussion and provision of detailed delivery models and costs, it was agreed that KCH CSDT would maintain the existing STB programme, including funding resources and allocating staff time to oversee the delivery of the programme. This involved developing a detailed transition action plan, including communications to settings, new consent forms and introduction of the KCH team to settings, all of which was overseen by LEAP’s Oral Health Promoter.

Sustainability has also been achieved through workforce development activities. A number of early years practitioners were trained in evidence-based oral-health messages. We hope that they will continue to use this knowledge to support families in their practice.

LEAP’s Community Engagement team were also trained by LEAP’s Oral Health Promoter to deliver community oral-health-promotion activities, such as children’s activities, so that oral-health evidence-based messaging can continue to be promoted at events until the end of the LEAP programme (as the oral health service closed in October 2023).

6.0 Key messages

- LEAP delivered an evidence-based oral-health-promotion service that was well-aligned with national policy and priorities.

- Training the workforce in early years oral-health promotion and engaging local communities are useful mechanisms for sharing evidence-based oral-health messages and practices.

- Engaging with local dentists was both useful and challenging. More should be done locally to ensure improved linkages with these key stakeholders so that more parents register their children with a dentist by age one.

- Childhood obesity prevention is linked to oral health improvement, particularly in populations at risk of worse outcomes. A greater focus on universal early years oral-health promotion across Lambeth, especially in areas of high deprivation, would support wider public health efforts to improve the health of the children who live in Lambeth.

7.0 Appendices

7.1 Supervised toothbrushing consent form

7.2 Slide illustrating rationale for including STB and provision of toothbrush packs in LEAP oral health service

7.3 Toothbrush train for holding toothbrushes in childcare settings participating in the STB programme

7.4 Oral-health pack including LEAP bag, a free flow cup, family friendly toothpaste, toothbrush and top tips for teeth health messaging card, and general information about LEAP

7.5 Oral-health puppets and oversized toothbrush used at community oral health promotion events

7.6 My First Visit to the Dentist and Gummy Gardeners promotional flyers

7.7 Top tips for looking after your child’s teeth leaflet, distributed at community events and in oral health packs

7.8 Toothbrushing chart, which was accompanied by stickers, given to families at community events

8.0 Acknowledgements

With special thanks to dental public health colleagues in NHSE’s London region for their review of this report.